India is said to have the third highest population of HIV positive people in the world. It’s no longer a disease anyone seems to talk about though there are fresh infections everyday. Funds are drying up and everyone’s looking away. But for those newly diagnosed, for those who have been living with it for years, hope comes from within the community

BY SOHINI CHATTPADHYAY | 2 February 2015

Saturday afternoons are marbles in a pocket: comforting, chattering, lovely to hold. Even if you don’t do much with them, stuck at work completing an annoying report, it’s nice to imagine the possibilities of the weekend stretching ahead. To have them humming in your pocket. They make Maitri Lakra stretch out her toes in anticipation, and think of taking home some of the spicy chowmein from the local market for dinner. But the best Saturdays of all, she says, are when they have a network meeting.

The Delhi Network of Positive People (DNP+) meets on the second and fourth Saturday every month, in the afternoons, with the smell of strongly brewing tea and a general air of school dissolving for the holidays. The DNP+ office is in an unloved part of Delhi – the grubby backyard of the upmarket Saket malls. The flat wears the pale flush of white tube lights all day, yet the cheer in these meetings is palpable. Backs are slapped resoundingly, shoulders gripped with unmistakable affection, the jokes are like those of a Bollywood awards function – all sexual innuendo or gossip. It is the closest I have seen to that public-school sentiment called bonhomie.

A young man stands up to call the gathering to attention, and looks like he may have a fit of giggles any moment. An inept class monitor, he secures a tittering audience. Between 50-80 members turn up at every meeting, with the numbers going up as the weather gets kinder. DNP+ has more than 1,500 members on its register at present; it began with 20-odd members when the organization was set up in 2000. Lakra’s Saturdays have been booked for the past ten years. She was diagnosed HIV+ in 2000 and started attending meetings in 2004 at the Bengal Network of Positive People (BNP+) in Howrah, a sibling community of the Delhi Network. There, too, they met Saturdays to speak of their humiliating, isolating disease and its severe medicines with complicated names. “Main Nisha hoon, HIV positive hoon aur mein Tenofovir, Lamivudine aur Nevirapine leti hoon,” (I am Nisha, HIV+, and I am on Tenofovir, Lamivudine and Nevirapine) says a 30-something woman, grinning as she negotiates the last of the unwieldy names. Here, they identify themselves by their names, their HIV status (or the status of a family member) and their drug combinations. There are smiles and nods in response, but the effect is not infantilizing: it is, in fact, infectious. They, too, are amused by the oddness of their introductions, theirs is a cheerful fellowship of permanent patients.

Lakra says that at first, she was intimidated at the meetings: the public speaking, the fancy words, the way the insides of her chest came unstuck and floated around disorderedly before they all turned to stone and sank down. Those Saturdays were anxious, queasy – her hands were sweaty, the marbles stony, slick with perspiration, not nice to hold at all. Later, she would realize (and chuckle) that that was possibly her first realization of Saturday being any different than the other days. Her life with her (first) husband was lived one day after another after another, a dense, unhappy blur. She refers to her second husband only as John, her nickname for him, never woh or he, often suppressing a smile when she speaks of him.

Every week when she started, she prayed they wouldn’t ask her to speak, and every other week they did. But soon, she felt disappointed the weeks she didn’t get to speak. She was learning more and more about the disease, and thought inwardly that she had learnt more than some others. The only problem was the pronunciation, and actually, there was one more thing. How to say that she was relieved that her husband was dead?

A name is called out and a man slouching at the back half-raises a hand. “Why have you stopped your medicines?” asks Manoj, one of those conducting the meeting. “I haven’t,” he says. “But you haven’t collected your medicines from the hospital, we have your log,” presses Manoj. “They were taking away my blood every time I was going to the hospital,” the man at the back snaps. “I am a poor man but I won’t let them use me. So I have stopped going to the hospital, that’s all. Who says I have stopped taking medicines?” he says. It turns out that he is taking some form of ‘ayurvedic’ substitute for his anti-retroviral therapy (ART). The HIV treatment requires regular blood tests – to check the CD4 count (the strength of immunity) in the blood and the viral load (the presence of the virus). CD4 or T-helper cells are white blood cells that fight infection. In hospital bureaucracies, these often end up getting done separately, leading to more frequent pricks. But his suspicion of the blood tests is only a ruse, it turns out: the reason the man has stopped going is the side-effects of the ART drugs.

ART is the treatment regimen for managing HIV. It checks the virus in the bloodstream and stems its mutation into AIDS. The Indian government has been offering the first of the three lines of ART for free since 2004. Some years later, it also started offering the second line of ART for free. The third line of treatment is only available in private healthcare at present, and is exorbitant, costing in the range of $1,500 (around Rs 92,000) per patient per year.

All ART drugs are expensive, in fact; India is celebrated for producing cheap, generic versions of these medicines and offering this complex regime of treatment free. The ART drugs have been central in changing the HIV positive diagnosis from terminal status to a lifelong condition that can be managed, not unlike diabetes. In a sense, ART has changed HIV from a death sentence to a life sentence – a prescription that has to be lived with.

Lakra’s own prognosis at the KEM hospital in Mumbai in 2001 was funereal. It was 2001, the government had no ART program, there were no HIV counselors on staff in hospitals, When her first husband fell very sick and didn’t get any better, he was diagnosed HIV+. Lakra, too, was tested then and the report came back positive. The doctors informed Lakra she would die. “I had never heard of the disease, and initially, I cried from the shock. Then, there was an immense sense of relief – it would all be over, soon. I called to God to take me before taking my husband because I knew he would say I had been whoring around. Later, when I joined the Bengal Network of Positive People, I realized that even without ART, people could live with HIV for several years with a careful diet and lifestyle. But there the doctors told me I was dead.”

Still, the ART drugs are vicious things, controlling as they do a potent, killer virus. Their effects on the body, understandably, are vicious too. Each ART drug, on the first line and the second line (no third-line patients were interviewed) have severe side-effects. For instance, Stavudine, a standard medicine prescribed for first-line ART patients, causes body weight to pile on at first. In a cheeky poster, Hari Shankar Singh, a member of the DNP+ stands full-length in a sideways shot. His belly is distended like a Bollywood heroine’s basketball bump. The poster reads, “No!! I am not pregnant.”

Then, the weight drains away suddenly, hollowing the cheeks down, savagely, to their veins. More worryingly, the drug ravages the liver, which is probably one of the reasons for the drastic weight changes. It took sustained campaigning by the positive networks before the National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) agreed to phase out Stavudine in 2012. This, too, was a whole year after the WHO recommended that the drug be discontinued.

Efavirenz, part of the most common drug combination in the first line of ART, is particularly feared. It is known to cause hallucinations. Many persons on the drug say it gives them bad dreams, most likely a manifestation of the hallucinations. Exhausted by the strange visions and the fitful sleep, several patients admit to slinking off the treatment at some point or the other. “Every one of the drugs has side effects,” says Lakra. “If a Crocin leaves you fuzzy, imagine what these drugs do.”

But the doctors at the ART centers have little time to convey this to patients. ART clinics are chiefly in urban areas, and each urban clinic treats hundreds of patients daily. The clinics are supposed to have counselors to provide this service, and they do. But consider the figures: AIIMS, Delhi the country’s most important and influential government hospital, has two counselors serving its ART clinic. The thrust of the responsibility is actually borne by the community of people living with HIV (PLHIV). There are 448 ART centers across the country serving PLHIV, the numbers of whom in India remain contested. In 2006, NACO estimated that there were around 2.5 million PLHIV, while in 2013, the UN pegged this number at 2.1 million.

“We have two meetings every month, and one is set aside for treatment-related issues,” says Singh, who also works as an advocacy officer for DNP+. “Treatment is the most critical part of our work. It is sabse agey [top of the agenda].” Members of the community are also appointed outreach workers in hospitals (at lower salaries than the counselors, who in turn are paid far lower than the doctors), and they do a stellar job reaching out to patients and helping them through the bewildering paperwork and procedures in hospitals. But in truth, they manage to connect with few patients amidst the chaos of hospital queues and doctors’ calls. The bulk of this work is actually accomplished by the network: outreach workers inform the network about patients who are not following up, based on logs maintained by the hospital. This was how the DNP+ took note of the man who complained of having too much blood taken out of him. The network then intervenes, working the advantage of peer pressure.

Positive networks play a surprisingly critical role in the medical treatment of the HIV community, aside from the social, psychological and emotional succor that support networks are typically understood to provide. They are like doctors’ waiting rooms (a metaphor borrowed from The Mental Illness Happy Hour podcast on The Nerdist) where PLHIV discuss drugs, their side-effects, lifestyle adjustments, and also how to communicate more effectively with the doctors.

The past few months have been difficult. Beginning August 2014, there were countrywide stock-outs of ART drugs and HIV testing kits. Every region was affected by the supply crisis, (because of the delay caused by a change in the drugs supplier and the tendering process to get the new contractor). The media, when it covered this, buried it in the inside pages. And in fact, much of the coverage was post-dated, filed as the perfunctory World Aids Day copy on December 1. The stock-outs were particularly severe for those on the first line of ART, and there were no testing kits for pregnant women. The worst of the crisis lasted about three months, but patients from different parts of the country continued to report shortages in certain drugs as I reported the story through November and December.

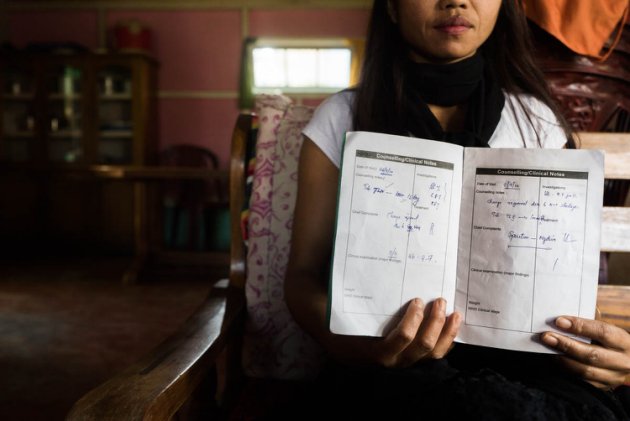

Dinesh, on second-line ART, faces challenges getting tested. Photo by Mark Antony:World Vision India

The crisis meant that ART drugs, which are collected by patients on a monthly basis, were distributed on a weekly, and in several cases, on a three-day basis. Going to the hospital to pick up medicines tends to eat up most of the working day, and patients usually take the day off work. Frequent hospital visits meant they had to take that many more days off work, and forsake their wages for the lost days. Not to mention, of course, the cost and inconvenience of travelling to the hospital and queueing up and getting papers signed.

In such situations, the likelihood of dropping out of treatment is very high. This was, of course, not the first time there were such stock-outs, and NACO officials I spoke to predict it is unlikely to be the last time. The ART regimen requires strict adherence and even a day’s medicine missed is believed to weaken the body’s immunity system. Three days of missed medicines counts as a drop-out case. Like in earlier years, the DNP+ was hyperactive: office bearers and staff called members in the network over the phone to emphasize the priority of collecting their drugs. They devoted all their meetings to discussing the difficulties in getting medicines, sent members to ART clinics to reach out to HIV patients outside the network, communicated these problems to doctors and negotiated short-term measures such as allowing pregnant women and older patients to collect medicines for longer durations, and worked with the Lawyers Collective to draft complaints to NACO. “To the point of annoying everyone,” says Lakra. “NACO was, of course, annoyed because we sent them letters drafted by lawyers. But members, too, were irked because we repeated ourselves ad nauseam.”

The Delhi State Aids Control Society (DSACS) is, indeed, annoyed. “How would you feel if you get emails every four hours, ki, phalana drug nahin mil raha hai (that such and such drug is unavailable),” says PK Nair, project director, DSACs. “See the network does do a lot of work, but they are also a nuisance,” he says. “Do you know how many patients each doctor sees in an ART clinic in a day? And did you know we get paid lesser than other doctors?”

It looks like the government practices a sort of HIV discrimination itself. NACO pays doctors in ART clinics Rs 25,000 a month, and the Delhi government pays ART doctors working in Delhi an additional Rs 10,000. The starting pay for doctors with an MBBS degree on the central government scale, meanwhile, is Rs 56,000. Dr Naresh Goyal, who handles information, education and communication at NACO, confesses to the difference in pay with resignation. “But what to do, there just isn’t enough money,” he says. Given the message of zero discrimination against PLHIV that the government broadcasts, this disparity in pay, while not against the PLHIV directly, is unseemly.

Mona, on ART since 2007, faces difficulties getting tested. Photo courtesy Mark Antony:World Vision India.

There’s also the long-running problem of surgery. If anything, the government’s ART treatment should have eased the process of getting a surgery done at a government hospital, as patients would likely be carrying a reference for surgery from another department in the same hospital. But the opposite happens: the moment patients reveal they are HIV+, they are made to wait. Many have learnt simply to suppress this information. Munna, a quiet shy man says his young son, who is also HIV+, once hurt his elbow while playing and it swelled nastily. When he took him to Safdarjung Hospital, the doctor in the emergency ward prescribed surgery. He was allotted a bed and when the doctor on duty came around, Munna informed him that his son was HIV+. “Then the khel started: tests were prescribed, and a set of medicines. When the results came in, I was told there was no need for surgery, medicines would be enough. So when I had to get my hernia operation done last year, I didn’t say.”

Procedures clearly differ from state to state, though: in Kolkata, every patient recommended for surgery is made to undergo a serology test before being wheeled into the operation theater. So a patient would be found to be HIV+ even if he/she did not mention it.

“They [doctors] don’t say no,” says Hari Shankar bhaiyya, who has become a ‘surgery-specialist interventionist’. “Now, everyone knows they’ll be in trouble for doing that, especially in a government hospital. So they ask for more tests, then when the test results are in, they say ‘you’ll be fine with medicines, no need for surgery’. If a patient goes back after that, they order still more tests and, of course, there’s the all-time favorite excuse – no beds available.” Singh initially speaks to the doctors as a representative of DNP+ before sending a succinctly-worded letter through the Lawyer’s Collective. “It always works. We’ve never had to go to court,” he says. “We send 6 -7 such letters every year but I am careful to use this as a second resort. I don’t want doctors to say that we send legal threats without even speaking to them.”

Until some years ago, the treatment offered to HIV+ persons in public hospitals, even those admitted for non-surgical purposes, was abandonment. Lakra remembers how patients were admitted and relegated to the last, filthiest bed in the ward. “The hospital in Purulia did not even have a sheet covering the mattress. Vomit and shit had caked on the mattress. Nurses would walk past but none would go near the HIV+ bed. There was a label identifying the bed as HIV+.” Lakra was the community care coordinator for the Purulia chapter of BNP+ from 2007 to 2009, and watched much of this unfold unembarrassedly when she accompanied HIV+ persons to hospital. She made up her mind, and a calm plan. One of the members of the Purulia network was a professional actor, she asked him to pretend to be exhausted with diarrhea, a common infection among the HIV+. A familiar sequence played out: last bed in the ward, no one walking near the patient for over an hour while he groaned audibly for water. Lakra had informed local television reporters of her plan, and when she asked why no attended to the patient and received an assortment of shrugs in reply, the cameras were pleased. “Quite a halla there was. I told the Chief Medical Officer Health (CMOH) then that things needn’t have come to this. I think they’re a little scared of positive networks from that time.”

* * * line drop

Positive networks are communitarian organizations, distinct from NGOs. They are, in a sense, the true manifestations of civil society, straight out of the dreams of Adam Smith, David Hume, and Georg Wilhelm FriedrichHegel. They are not funded, and emerge out of the need for creating community. They might befunded if they are given projects to administer by the government or NGOs, but they exist independent of funding structures. For instance, the Kolkata Network of Positive People has had no projects to work on for the past few years but the network exists nevertheless. DNP+, on the other hand, has its hands full with projects and can afford an office and regular rounds of chai and snacks for visiting reporters.

The government provides the funds and resources and infrastructure for the HIV program, while NGOs plan projects and administer them to an extent, sometimes bringing in international funding. The work of accomplishing the projects and looking after the HIV+ community is done by the networks. The government is the Chief Financial Officer, the NGOs are consultants and managers, the networks are the staff. But they also sometimes function as managers, union leaders lobbying for changes in the program, and activists protesting the agenda. The positive networks preceded many of the government’s central initiatives that are now in place: the ART treatment in fact started only in 2004, after years of lobbying by PLHIV for help with treatment. They are also the principal organizations fighting discrimination against PLHIV, and often rescue them from physical attack and property grab. On December 7, 2014, The Times of India in Kolkata reported the case of an HIV+ woman who, with her HIV- sons, was chased out of her home by her neighbors and assaulted. The police and local government officials didn’t help until the district network in the South 24 Parganas stepped in. Such attacks are still commonplace; Sabita Das, a member of the board in the Kolkata Network of Positive People (KNP+) says they hear of one case a week, on average. But they rarely get reported in the media. This story found a place possibly because of the involvement of a Trinamool Congress leader, or perhaps because it was a Sunday – a lean news day.

Networks are organized by district in India. Every district typically has one positive network, thus there are 19 networks in West Bengal. The parent network, which oversees all 19, is BNP+. Delhi, however, has three networks, which makes sense given how far the city stretches into its suburbia. One of these is specifically a women’s network – the Delhi Positive Women’s Network. The Indian Network of Positive People is the umbrella body that oversees the district and state networks. INP+ corresponds to the NACO. NACO, in turn, administers state AIDS control societies, commonly known as SACS, in each state.

As support groups, positive networks are something in the nature of church communities. The Alcoholics Anonymous (and Narcotics Anonymous) community, for instance, rests on a 12-step program that invokes God at nearly every step. Positive networks don’t charge God with the responsibility for their well-being, but are rather similar to church groups in their emphasis on helping the community: it is unusual for a member to be admitted to hospital without the help of the network, job vacancy announcements are made at every meeting, and exhortations to pass on the word about jobs are made. AA groups are rather more aware of class and wealth – affluent or even well-dressed members tend to enjoy influence. The networks are more of a meritocracy in this respect: those who work for the community earn the regard of their fellows.

Fearing discrimination, Lily’s parents keep her status a secret. Photo courtesy Mark Antony:World Vision India

Lakra found the first, and indeed, every one of her jobs through the network. When she first started attending meetings at BNP+, they paid her bus fare. She had such little money then that she saved the fare, and came on foot with a bottle of water, leaving her younger son in the custody of her older boy. She hung around and listened. The network started paying her Rs 400 to make tea and wash cups and clean the office. She started taking calls when the office was empty, and she graduated soon to the position of office assistant, though at the same salary. When the international NGO Population Concern International organized a countrywide walking tour to raise awareness about HIV-AIDS, the Bengal network had to send a team to receive the participants and walk with them through the state. Lakra asked to go, and was sent on the month-long assignment: her first real ‘office’ job where she got to travel, and a salary of Rs 3,000. At the moment, she works as a community outreach worker with the ART center in AIIMS, a position of considerable respect and responsibility.

The networks have had a central role in formulating the HIV and AIDS (Prevention and Control) Bill, which has been ready since 2007 and has been ‘this close’ to getting passed for at least three years now. “The principal insights came from the community,” says Raman Chawla, who works in the HIV unit of the Lawyer’s Collective. “They knew the most insidious and intricate ways in which discrimination works. For instance, an employer might say they have no problem with an HIV-positive staffer, but if they don’t allow them leave when they need it, that doesn’t amount to much in real terms, does it? You and I, we can be the fiercest advocates of zero discrimination towards PLHIV, but we only know their lives from the outside.”

The Bill is at present being deliberated by the Cabinet, and the word in the Lawyer’s Collective office is that it will be okayed. But there have been close calls before; the Bill was tabled in the Rajya Sabha in 2013 and sent to a Standing Committee for comments and changes, but didn’t move thereafter. There is definite momentum this time though, Chawla feels. He had smiled wanly late in 2013 when the Bill was being tabled under the UPA government. This time, he wagers an estimate: the Bill will be passed in the next six months.

But it will be a somewhat hollow victory: the Bill will likely be passed without offering protection from discrimination to sex workers, drug addicts and men who have sex with men (MSMs), which are among the communities most vulnerable to HIV. The biggest threat, says the Lawyer’s Collective, comes from the growing drug problem in the country, of which Punjab is the most well-reported case. The Bill also does not guarantee ART treatment to PLHIV; it says treatment will be offered “as far as possible” – a problematic formulation that might well undermine the government’s responsibility, even during a drug stock-out. This is at variance with the Supreme Court order of 2010 directing NACO to “ensure universal access to second-line ART in a phased manner”.

Funding for HIV-AIDS is also on the wane. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria cancelled its 2011 round of grants because didn’t have the money. A Guardian columnist read the development as “HIV/AIDS going out of favour”). Later, the Global Fund put in place a new funding model which calibrates its commitment on the basis of a country’s income-level. The highest commitment is to lower-income countries, and India, while still eligible for aid, falls under the category of Lower Middle Income country.

And in 2014, the government cut the budget for NACO and subsumed it under the health ministry, taking away its independent charge. Earlier, NACO had its own secretary, who did not have to report to the Health Secretary. Now, there is only one Health Secretary administering the ministry of health. DSACS estimated that the budget cut would amount to about Rs 500 crore a year. The NACO budget for 2013-14 was Rs 1,400 crore. The lack of autonomy means delay in decisions, because everything has to be okayed by the Health Secretary. The stock-out problem this year can be partly attributed to this. Funding for the Lawyer’s Collective for working on the Bill has also ceased. “Overall, the sense conveyed by the government is that HIV is not a priority any more,” says Grover. “That this problem has been tackled. And there are sexier problems on the horizon like Swachh Bharat Abhiyan,” says Anand Grover, director of the Lawyer’s Collective, tartly. The media echoes this sentiment; editors smirk off HIV stories as tearjerkers.

Sunny and his wife cannot afford regular trips to ART centers. Photo courtesy Mark Antony:World Vision India.

According to the United Nations, India has the third-largest population of people living with HIV in the world. Though the rate of new infections has dipped (they declined by 19 percent between 2005 and 2013), new cases are being added every year – India accounts for 38 percent of all new HIV infections in Asia. At one point, in the late 1990s, we looked set for an epidemic of AIDS deaths. “If we have been able to check the HIV crisis in India, it is only because of the community,” says Grover with that touch of hyperbole that goes down well at press conferences. “Our condom-use campaign is a success because we took the help of sex workers to spread the word. But in Thailand, where the military regime took a top-down approach, condom use is still not a common practice in the sex industry,” he adds. For the hundreds of thousands who live with the virus, it is the networks that offer community, acceptance, advice, laughter and often, a sense of self.

* * * line drop

The Girls Who Are Born Again [subhead]

It is easy to tell the new members from the older ones in the meetings: the newer ones sit quiet and rigid, their faces tense. The older ones gossip and joke, and often speak over others. This transformation is the most vivid for the women. Almost all the women who attend network meetings are homemakers, who had never worked outside the home until they joined the network. The networks push them to speak and to work, typically in AIDS awareness but also in other fields, and to articulate whenever possible their rights as HIV+ persons and as women. The networks recommend their members for jobs with NGOs and government work on HIV-related issues, and many, many women come into their own with these opportunities.

Maitri Lakra was once Debjani. She started attending meetings at BNP+ in Howrah, West Bengal, in 2004 after her first husband died a painful and exhausting death from bone tuberculosis and she was thrown out of his village. Living with her two sons in a house that she built with bamboo and black tarpaulin sheets on an abandoned patch of land made available to her by a gram panchayat member, she was surprised to find her permanent fatigue lifting gradually. Her husband’s last days were torturous for her. He would fling aside the food she cooked, spit his pills into her face, scream about her infidelity even when he lay dying in hospital.

‘Puii’ is president of Mizoram’s network of positive people. Photo courtesy Mark Antony:World Vision India.

“I didn’t get one moment of peace with that man,” Lakra says.

She was tricked into marriage after her Class X exams by her loving family when she went for a post-exam vacation to Bombay. Startled by the turn events took, she was too dazed to refuse. She spent most of her marriage in a daze. Her husband, a Bengali jewelry artisan in Bombay, was almost two decades older than her and so suspicious that he didn’t allow her to speak to neighbors. He was so nasty that she trained her bladder so she only needed to use the bathroom in the morning and at night. “There were always people near the bathrooms and they would smile and ask after me. My husband said I was making plans to hook up.” The queues for the bathrooms in the morning and late evenings, after people had returned home from work, were long and Lakra barely managed to bathe.Her father heard of the network in Howrah, and accompanied her to her first meeting. After she got a job there making tea and washing dishes, she met her second husband on her first network assignment. Najaraus Lakra (or John, as Lakra calls him affectionately) is a slim, boyishly attractive young man who is still HIV-negative. Najaraus was part of the team from Population Control walking across the country to raise awareness about HIV. The BNP+ had warned Lakra and the other women sent to escort them not to chat with the men too much. As HIV+ women and widows, they were seen as bad girls anyway. But Najaraus pursued her, and wasn’t deterred even when she introduced her two sons to him. She was impressed, and they married in 2009 after a marvelous phone romance.

She has been working steadily in the HIV-AIDS field since that first Rs 3,000 assignment. She has headed district positive networks, demonstrated the use of condoms on glass tubes in public awareness programs, and calmly travels into desolate Delhi nights to help admit a new member or newly-diagnosed HIV+ person to hospital. Through it all, her relations with her own family have been thorny, at best, aside from her closeness to her father. Her uncles and aunts won’t eat with her. Her sister and mother said to her, when she was getting married to John, ‘Why do you want to bring us more disrepute?’

At networks meetings now, Lakra grins and giggles, never the busybody cornering speaking time, but speaking only when asked to; relaxed, poised, not funny herself but laughing heartily at the jokes others make. She is quite the practiced public speaker.

“The other day, somebody from the Bengal network was visiting the DNP+ office and told me, ‘I knew you as Debjani!’ I said that girl with oiled hair and drab saris is gone. Now, I wear jeans and drink cups and cups of chai in street corners like men,” says Lakra. She doesn’t say it, but she also pronounces ‘condom’ without lowering her voice like most of us do.

[—line drop]

It’s not only the women, though. The people in positive networks generally have a higher degree of openness. They have frequent interactions with addicts, sex workers, MSMs and transgendered people, and get to know them as colleagues in activism, rather than the exotic species that we view them as. They share discussion fora with them, and at times, meeting spaces too. Positive networks include members of these communities, but over time, drug users, sex workers and MSMs have forged their sub-networks, the idea being that like listens to like. Somehow they have cracked a code of democracy we are still struggling with: they manage to listen respectfully to the specific concerns of drug users though their own agenda might be quite distinct. They dive headlong into raucous sexual jokes, and gleefully break into the hijra clap routine at any opportunity. How does it all go so warm and fuzzy, as if it were the script of a Raju Hirani film? Is it possible then that in their collective sickness, they are healed of our spiky prejudices?

Many years ago, I was invited to an HIV conference in Calcutta. There was also a photo exhibition on the sidelines. There, I read a poem whose lines often come back to me unbidden:

I am neither the giant of my dreams;

Nor the dwarf of my failures.

I’ll bet it was written in a positive network meeting.

Originally published on Yahoo Originals