This film on the real-life Nipah outbreak in Kerala in 2018 is the opposite of a didactic film like Toilet: Ek Prem Katha. It’s moving, humane and intelligent

The thing that I loved most about the Malayalam film Virus is the haughty “Delhi team” that arrives to take stock of the Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala in 2018 and peremptorily decides that it is a terrorist bio-attack, given that the index (first) patient is Muslim and worked in the Gulf. They listen to the briefings on meticulous contact tracing arranged at Kerala health minister CK Prameela’s (modelled on the real-life health minister Shailaja ‘Teacher’) home with unconcealed, firmly congealed, impatience. The film got that officious, huffy expression that sums up Delhi (central babus but also media, NGOs, thinktanks, universities, writers) beautifully. Delhi does not have the time to listen to rigorous, scientific protocol-based work, Delhi works on magical instincts. This is the myth of preternatural Delhi efficiency that underpins the Neeraj Pandey school of spy thrillers where procedure-focussed babus hold up prescient R&AW officers. But strangely enough, it is also a line of thought that file-wielding babus themselves and the entire constituency of Delhi residents who work in air-cooled offices subscribe to, including the migrants who have settled in the city. That Delhi is a buzzing, well-informed nodal point where things work because people “know things”. They just do.

A supremely well-functioning Central government hospital like AIIMS creates the impression that the Centre does its job well while the state governments are busy politicking. The opposite is true and recent events have laid out that better than I ever could: the Centre does not pay GST dues to the states depriving them of revenue, it plays politics along the Hindu-Muslim axis, it throws shade at state governments administered by Opposition parties. Virus articulates all of this beautifully, to show what happened during the Nipah outbreak

Virus shows up this superciliousness, and its hollowness beautifully. If you remember the Tabhlighi Jamaat controversy early in the Covid19 lockdown, isn’t this exactly what transpired? The Central government declared an international conference organised by the Tablighi Jamaat, a Muslim missionary movement, a super-spreader event which caused Covid infection numbers to soar. Some leaders of the BJP, which is in power at the Centre, called the event “corona terrorism”. Several Hindi and English language news channels with large viewership amplified this sentiment by calling it “Corona Jihad”. Around the same time, news of several other mass gatherings emerged: a powerful political wedding in Karnataka attended by large numbers and captured in photos, a temple celebration in the state of Tamizh Nadu attended by about 350 people, Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath attended a temple ceremony attended by large numbers of people and press hours after the nationwide lockdown was announced. Several more have taken place in subsequent weeks, none of these events were termed terrorist or anti-national.

Some months ago, I had a row on Twitter with doctors and health reporters I hold in very high regard when they criticised a cut in the AIIMS budget. At the time, I had spoken inarticulately about why the budget cut for AIIMS is good because it cuts the Centre down to size. A supremely well-functioning Central government hospital creates the impression that the Centre does its job well while the state governments are busy politicking. The opposite is true and recent events have laid out that better than I ever could: the Centre does not pay GST dues to the states depriving them of revenue, it plays politics along the Hindu-Muslim axis, it throws shade at state governments administered by Opposition parties. Virus articulates all of this beautifully.

In the film, the terrorism diktat from Delhi is neatly cancelled by meticulous contact tracing and basic public health groundwork. How does this academic material translate on screen? It’s surprisingly moving, thanks to the performances of Parvathy, who plays the contact tracer. In one sequence where she visits a Nipah victim’s home, she accepts a cup of tea. “I thought you wouldn’t drink our tea,” says a family member. Parvathy gives the tiniest nod of acknowledgement without speaking. All of the film is like this, quiet, sensible and deeply moving.

In its format, Virus is modelled on the multi-braided narrative of Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion. But the eventual impact is far more affecting, even more humane somehow. Perhaps my most favourite moment in the film is when Revathy, playing the real-life Kerala health minister KK Shailaja, says it explicitly. “Let them see me as a human being,” she says, when she is asked to wear PPE to visit the last two Nipah patients in hospital who have recovered, officially ending the outbreak in the state. Revathy is devastatingly effective—for much of the film, she doesn’t speak except for the end where her speech will make you tear up. Guaranteed. Perhaps this is the secret of Shailaja ‘Teacher’s success, now globally acknowledged: she listens to expert advice, she doesn’t inflict her “mann kii baat”.

And then there is the very last sequence, the epilogue, which mirrors Contagion. There, the index patient was infected when she sought to meet the chef at a restaurant she was eating in. He is cleaning a pig when the request comes in, and he wipes his hand on his chef’s apron before he shakes hands with her. An act of love and connection. In Virus, the epilogue is even more forgiving: the index patient finds a baby fruit bat on his path while riding home. He picks up the terrified baby and puts it back in the tree. So much for terrorism. It was an act of love.

Virus is streaming on Amazon Prime in India.

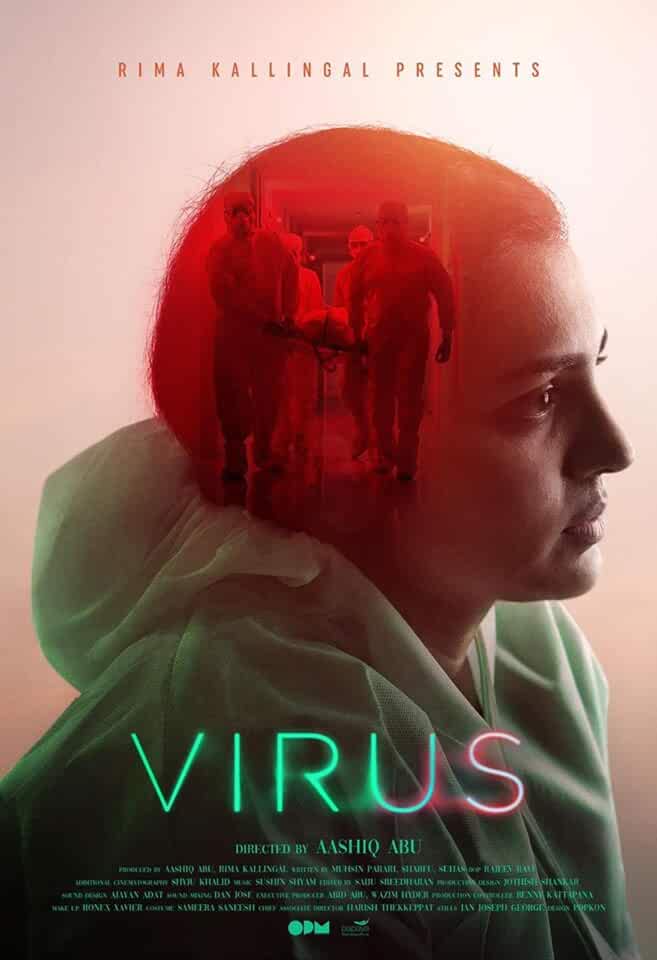

Director: Aashiq Abu

Starring: Revathy, Parvathy Thirovothu, Tovino Thomas, Kunchako Boban, Asif Ali and others