Shabaash Mithu acknowledges what I found to be the sportswoman’s main problem in India—the un-seeing of women’s sport as proper sport. The un-seeing of women as equal citizens. The result is a thousand daily indignities, such as no money to travel, no international exposure, hand-me-down uniforms of the men’s team, bureaucratic scorn. The story of women’s sport is a search for meaning in routine humiliation, more than world-beating triumphs. But the film does not trust this answer. It looks for bigger dramatic moments.

By the second half, Shabaash Mithu has run out of major conflict points. Mithali Raj’s family has come around to her unconventional love for cricket, her uncomfortable start in the women’s cricket team as a result of her comfortably middle-class background is smoothed over by her excellent performances in the field. What remains is her continued rise and rise in the game, the story of an unquestionable great shining consistently in shabby, listless circumstances—a technically beautiful, disciplined batter unwatched by viewers, barely given opportunities to play by her country because there is no interest in women’s cricket.. A number of low-stakes incidents follow one another—Raj feeling slighted by the disinterest in women’s cricket compared to the obsession with men’s cricket, a petty jealousy within the team.Even the promising confrontation with the cricket association which builds to a nice moment of scorn dished out at Raj and team is wrung into a waste by a plot development that appears meaningless. If the incident was a statement to the cricket board, the meaning of the episode is left unarticulated, unexplained, in a film that generally tends to over-exposition.

It is not that the incidents are irrelevant because they are banal and everyday. In fact, it is the ceaseless, endless nature of indifference, of doing things without being seen, that typically wear us down to breaking point in our lives. Isn’t it? But Shabaash Mithu does not reflect on the chafing away inside that takes place when we feel unseen and unvalued. What we see are a series of incidents on screen—no toilets for women, team shirts with the names of the men’s cricket team, no recognition from cricket viewers—without seeing the inner workings of Mithali Raj’s mind. Consequently, the events on screen feel like a series of events said without feeling, like a newsreader reading out the news.

This is a pity for at least two reasons. The first is Taapsee Pannu, who develops a competent batting technique by the end of the film. In the climactic World Cup performance of the last twenty minutes, the action between bowling and batting is mostly taken in single shots, without editing, to get to a close-up of Pannu batting. This is not the case in the first half, where the bowler’s action is followed by a cut and a closer shot of Pannu’s batting, clearly for the camera. In the second half, Pannu is batting less for the camera than she is for the game, so to speak, connecting bat to ball competently. Mithali Raj is a superb batter, a treat to watch (go to YouTube and see if you haven’t yet), and it is implausible to expect an actor to get into Raj’s groove. Pannu is not Raj. What she does is connect bat with ball believably, credibly, in the longish overhead shots taken of the pitch. The World Cup action was likely shot towards the end of the shooting schedule. In interviews, Pannu has said that the pandemic helped the film because she got six to eight months to train for cricket instead of the couple of months assigned at first. Clearly, she used the time to practise. The difference in camera shots between the first and second halves testifies to her increased confidence.

In Hindi cinema, there is a long, rich tradition of actors shaking their fingers earnestly to invoke playing the guitar. Piano sequences are shot by obscuring the hands when the face is in the frame, and disembodied close-ups of playing fingers. Accents are displayed by exaggerated pronunciations, often mispronunciations, of single words or phrases—“iish” in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas to invoke the Bengali identity, “aiaiyyo” in countless Mehmood films to demonstrate ‘Madrasis’, the song ‘Aami Je Tomar’ and the mispronunciation of “kaal”(tomorrow or yesterday) as ‘call’. Even the generally reliable Amitabh Bachchan, who is married to a Bengali woman, overemphasised the ’o’ in Piku. In other words, there is a storied tradition of unembarrassed shortcuts. Given the relatively large sums of money lead actors in mainstream Hindi film have always been paid relative to other industries, I’ve often wondered at this slacking off: can’t they spend time with a language coach or learn a musical instrument as preparation for a role? They spend enormous amounts of time dressing up and, now, at the gym. Surely, the non-look aspects of a role also deserve investment?

Over the past two decades, the attention to detail has been improving, thanks perhaps to Aamir Khan’s box-office success with ‘method acting’. But in the sports film, among the three most popular genre films in Hindi cinema today (the others are the historical and the spy film), there is the shortcut of playing the coach. Several major stars play the coach in the sports film—Aamir Khan in Dangal, Shah Rukh Khan in Chak De India, Amitabh Bachchan in Jhund, Ajay Devgn in the forthcoming Maidan. This enables a big star to be a part of a sports film without really investing in the time needed to play competently. True to his reputation, Aamir Khan did indeed wrestle competently in a portion of Dangal, though he was coach for much of the film. In Lagaan, of course, he was convincing as top-order batsman besides wearing a noticeably slimmer midriff.

In this sense, Pannu is an equal. She plays cricket believably. So much so, that I enjoyed the last twenty minutes of Shabaash Mithu, unlike several other critics who found the sports action boring and plot-less. I enjoyed it because I liked the fluidity of Pannu’s cricket. Several of the players in Shabaash Mithu are state and university level players, and it showed in the cricketing action, especially in the last section where Pannu is up to speed with them.

A number of observers have pointed to Pannu’s sports avatars in film. Indeed, she has played hockey players twice—in Soorma and Manmarziyan, a shooter in Saand kii Aankh, a track athlete in Rashmi Rocket and now, a cricketer in Shabash Mithu. In Manmarziyan, Pannu plays hockey for perhaps a total of a minute on screen but her physicality and her walk and her repeated running in the film look believable. The sports scenes in Rashmi Rocket are, sadly, embarrassingly filmed, so it merits no discussion. Aside from this, she has played very physical parts in the action films Baby (2015) and Naam Shabana (2016), where she essays the part of an Indian spy called Shabana Khan. In the Telugu film Neevevaro, Pannu has another role that emphasises her physicality in a twist. In the slim, delicate world of Indian cinema’s leading women, dancers are more common and celebrated—consider the careers of Vyjayanthimala Bali, Waheeda Rehman, Hema Malini, Madhuri Dixit, Aishwarya Rai, Deepika Padukone. Pannu’s physicality is unusual and an asset that several filmmakers have noticed and utilised. To her credit, in films like Shabaash Mithu, Naam Shabana, Baby, Soorma, Manmarziyan, the physical training she has put in for the parts is evident.

Pannu herself is perhaps not adequately aware of her unique contribution. When I met Pannu briefly, I was introduced to her as a film critic. In response, she told me that Pink onwards, the critics have taken note of her work. But Pannu’s performances, to my mind, are not limited to realistic or natural acting performances—which are chiefly considered “good acting”—alone. Her performances are also physical, in the way that Waheeda Rehman or Vyjayanthimala or Hema Malini or Madhuri Dixit’s performances are enormously about their dance.

Pannu’s performances, to my mind, are not limited to realistic or natural acting performances—which are chiefly considered “good acting”—alone. Her performances are also physical, in the way that Waheeda Rehman or Vyjayanthimala or Hema Malini or Madhuri Dixit’s performances are enormously about their dance.

In the Natya Shastra, abhinaya means expression and comprises four elements—bodily expression (angika abhinaya), spoken expression (vachika abhinaya), costume and make-up expression (aharya abhinaya) and spiritual expression (sattvik abhinaya), which translates to broadly the substantive feeling invoked by an individual performer. In Indian cinema, it is spoken expression that is considered the essence of acting (actors are chiefly remembered for their lines and stars for their mannerisms), and in recent years, the costume and make-up. While the body is sculpted and buffed in the gym and yoga studio, bodily expression is seldom considered to be a part of acting barring the adoption of prop characteristics such as a limp or a lisp or a particular mannerism. For women, good dancers are often considered separate from good actors; rarely is dancing considered a part of a performance. Pannu is even more unusual. She is not considered a good dancer, yet uses her body to perform.

There is a second reason for regret in Shabaash Mithu. The story of Indian sportswomen is often not a story of overcoming immense odds, but of having to facegeneral indifference and apathy. I say this from my work on a book on Indian women athletes. It seemed, when I began, that the stories would be of explicit issues such asgirls not being permitted to wear sports clothes, like the headlines of stories on the tennis player Sania Mirza when she came to national attention in the mid-2000s. Although this, and the desire to keep women’s bodies indoors and out of sight, is common to many women, itis typically the initial hurdle. Almost all women who choose a career in sport overcome this fairly early in their lives. But the real grind in women’s sport in the subcontinent is the indifference to their sport. The un-seeing of sportswomen, as if they are the participating contingent, not in real competition,the also-theres. This indifference is from the government and the sports bureaucracy, but also from society. Us at large. As a result, women’s sport is a low-stakes project, filled with banal problems and petty slights. These would be true even for an undisputed great like a PT Usha, because the environment of women’s sport as a whole is one of indifference.

Women who choose to make their lives in sport fight the major battles at home, in the neighbourhood, early on. But it is the daily indifference—the lack of money to travel, the lack of international exposure and training, the absence of standard facilities, the contempt from the sports bureaucracy for not performing—that is the real grind. Sport as a whole, barring cricket, does not matter to our society. Women’s sport, even less so. Unlike men’s sport which is considered a barometer of national effort, women’s sport is considered an ornamentation. An add-on. Like the armyofficers’ wives’ flower show.

Faced with this everyday, ceaseless disinterest, the real conflict in women’s sport is the search for individual meaning. No one sees sportswomenas national representatives. And because of this, the women often do not consider themselves so either. Rather, sport is a means to a slightly better livelihood, the sought-after Group D government job, the avenue for a bit of self-respect.

Such was the struggle faced bythe athletes I profiled in my books. The stories of these women are not stories of individually dramatic odds but small, low-stakes incidents that eat away at you. National pride is almost never at stake because they are rarely given the opportunity to perform for the nation. Rather, the battle is private, the individual’s search for meaning amid apathy and erasure, and boredom.Bereft of big dramatic episodes, this is not easy to bring out. Indeed, it is not easy to articulate either. Many athletes did not identify the everyday apathy that had eaten away at them. They looked for the big losses on the field. For me, the hardest thing in the book was to piece together their search for meaning and self-respect amid this disappointment and boredom. I don’t know whether I have succeeded in this but I recognised the conflict was small and internal, not dramatic and explicit, and I tried to bring dignity to that.

Shabaash Mithu acknowledges this with a self-aware sequence where a teenaged Raj makes a list of “haves” and “have-nots”. Under haves, she lists her family, her coach, her school, her friend. And under “have-nots”, she finds nothing to write. This is likely even more true for an individual like Mithali Raj who is unusual in Indian women’s sport in that she comes from a comfortably middle-class family with good education, and never had problems of indiscipline. Raj is an outstanding sportsperson but no one cares or watches or knows. Her struggle is to find a sense of meaning in continuing to do what she does, unwatched, barely permitted to play even.

The makers of this film know this, asdemonstrated by the “haves/have-nots” sequence, but they are not satisfied with it. They want more drama, and they attempt to infuse Raj’s seemingly conflict-free life with bigger moments. The writer and critic Deepanjana Pal found a telling example of this: in her review, Pal pointed to an “ask me anything” session that Mithali Raj conducted on Twitter where she was asked who inspired her to take up cricket. In the film, this is shown to be a childhood friend, a Muslim girl called Noori. In the twitter AMA, Raj made no mention of Noori, speaking instead of her father and coach. The Muslim friend was possibly an exaggeration, a partly fictionalised element from Raj’s personal memories.

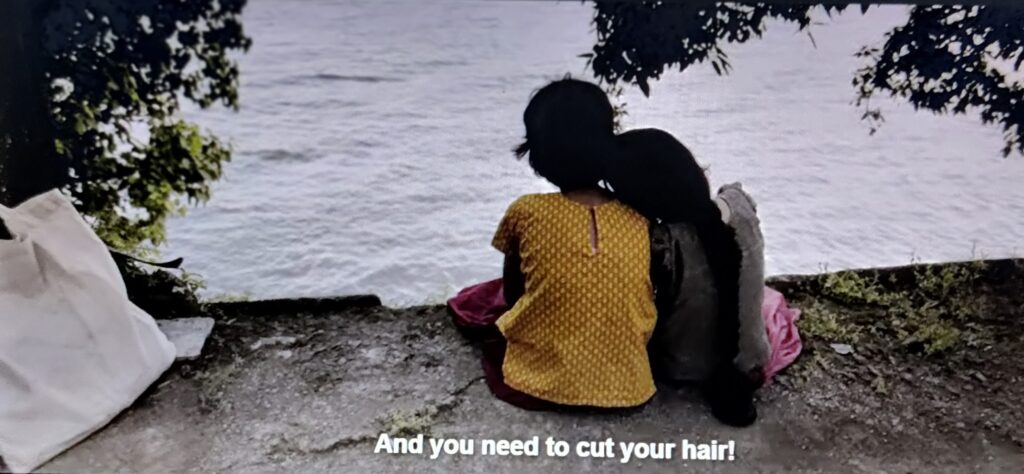

This friendship at the start of the film is perhaps the best part of the film. The two 8-odd-year-olds are charming characters. Moreover, female child characters are unusual in Indian cinema as a whole;boy characters, on the other hand, are far less so.This is likely the legacy of Satyajit Ray’s Apu in Pather Panchali.A female friendship, in particular a childhood friendship, is even more uncommon. To see two girls playing outdoors, sitting and chatting outside, is rare even in real life in many parts of the subcontinent. Families tend to want to protect girls, understandably so. These sequences of girlhood outdoors on screen suggest a right to the outdoors no different from boys—an equal citizenship.

Later in the film, this friendship is revisited to help Raj overcome her disaffection with cricket. Noori returns suddenly to Raj’s life, and tells her that she must play for all those Nooris who could not play. Her Muslim identity makes this a larger point about Muslim women, and not only Indian women. The intent cannot be faulted but the point does not come through, because it is made through exposition and not, say, Raj’s own memory of her friend and her love for the game. (The adult friendship is also completely flat, unlike the delightful chemistry of the two young girls.)

But Pal’s point remains: is this friendship mainly an exaggeration? If yes, is it fair? When you claim to be telling the story of the real life cricketing great Mithali Raj, how much are you permitted to fictionalise?

Perhaps, this is the nature of a visual and more mainstream medium like a Hindi film with a big star. You want to tell a story that has explicit elements—a memorable friendship, a marked antagonist, an arranged marriage conversation where Raj compares her national playing duties to an army officer’s call towar. In real life, Raj appears determined but reserved, the sort of person who would leave most things unsaid and speak throughher performances. Pannu channels this quietness reasonably, invoking an introvert even though the screenplay moves into exposition mode and puts her in the position of an outspoken captain. Both Raj and Pannu, I felt, are let down by the film’s decision to over-state things. But what if the film opted for a quieter story, of a woman worn down by everyday indignities like having to squat on the road to pee? A woman who finds a sense of meaning though nothing really changes, because she realises that she has chosen to make this her life.

This essay was first published on the New India Foundation’s website.