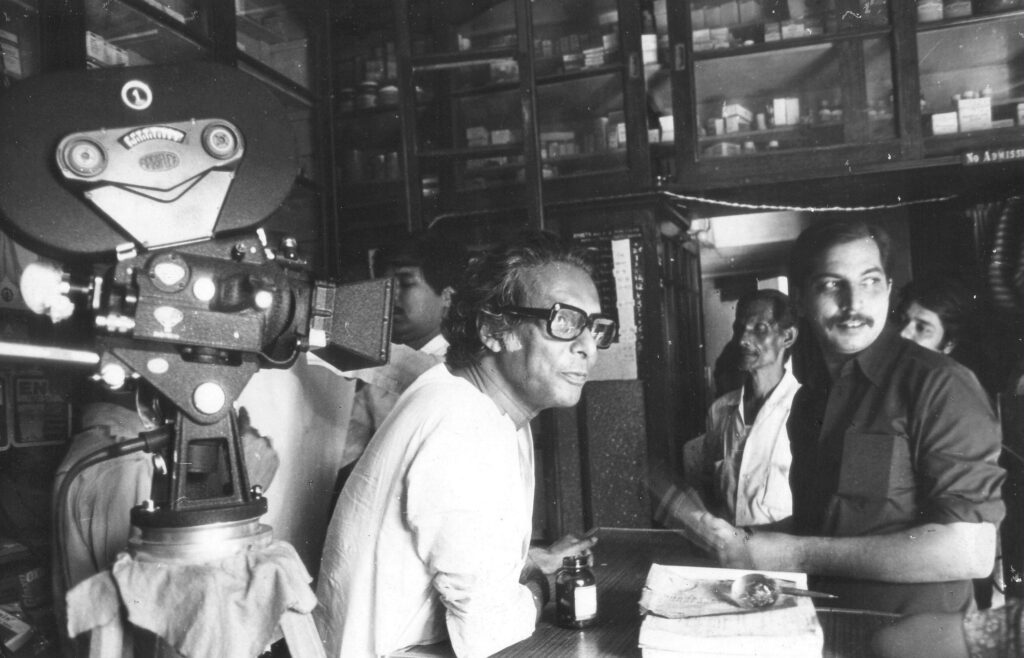

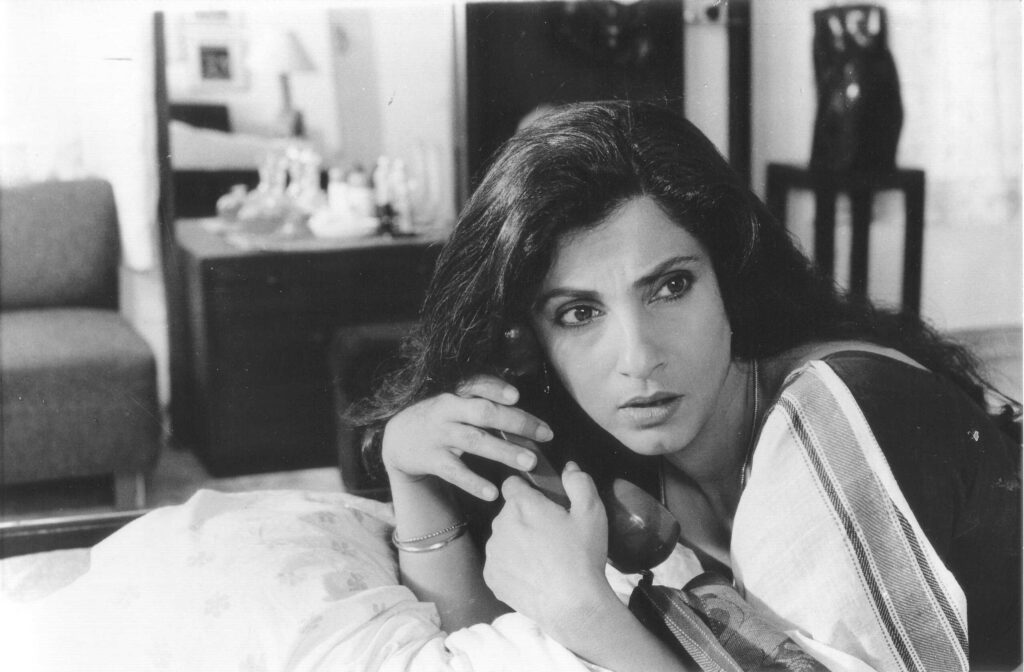

Mrinal Sen (1923-2018) directed 27 features, 14 shorts, and five documentaries in a 47-year-career, working with actors like Dimple Kapadia, Mithun Chakraborty, Mamata Shankar, Simi Garewal, Shabana Azmi and Dhritiman Chatterjee, among others.

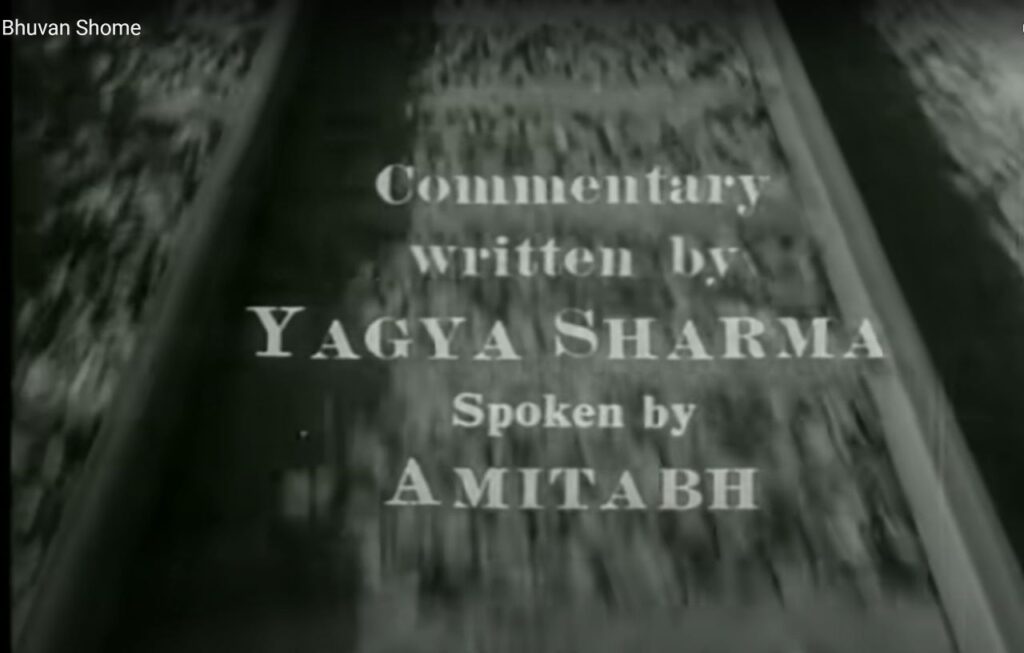

More than one film lover has noted the intriguing similarities between Lagaan, the 2001 Hindi film that became the third Indian film to be shortlisted for the best foreign film Oscar, and Bhuvan Shome, the 1969 Hindi film that is often called the first landmark film of the new cinema movement in Hindi cinema. Aamir Khan is called Bhuvan in Lagaan, and Gracy Singh Gauri. Utpal Dutt plays the Bhuvan Shome of the title, and Suhasini Mulay is called Gauri. Both films are situated in the rural Saurashtra-Gujarat terrain, both star Mulay in prominent roles, and both feature a voiceover by Amitabh Bachchan.

“The first film I have a memory of seeing is Bhuvan Shome,” said Ashutosh Gowariker, director and writer of Lagaan, over the phone. “I was four years old and it left an indelible mark although I was too young to appreciate the film really. When I was working on Lagaan, my first period film, I wanted a name that sounded like it was from a different time. I chose Bhuvan. I had loved Utpal da and Suhasini ji’s performances in the film, so I went to meet her with my script. At that time, she was not acting. In fact, Lagaan was her second film after her return to acting [in Gulzar’s Hu Tu Tu]. She was Gauri in Bhuvan Shome, so I called Gracy’s character Gauri. The only thing that was not a conscious tribute was Bachchan’s voice. I went to him because I needed a voice of God for the film.”

The first work of Amitabh Bachchan that was released was his voiceover for Bhuvan Shome. Mrinal Sen was a friend of Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, the director of Bachchan’s debut Saat Hindustani, and would frequently visit his house while working on Bhuvan Shome. It was here that Bachchan introduced himself to Sen. “Mrinal da, aami Bangla jaani. Aami Kolkatay chhilo (I know Bengali, Mrinal da. I lived in Calcutta),” Sen writes in Montage, describing the meeting. “Your Bengali is lousy but your voice is great,” Sen said. He is credited as ‘Amitabh’ in the title credits of Bhuvan Shome.

The film marks an unexpected coming together of two strands of Hindi cinema as it would shape up over the 1970s and 1980s. In 1968, Sen and Arun Kaul published a manifesto for the new cinema movement, an extension of the political unrest in the late 1960s in India particularly the Naxalbari movement, writes film scholar Soumya Suvra Das in a paper on the New Cinema Movement, as well as a response to the French New Wave and American underground movements in film. One response of the mainstream Hindi film industry was the middle-class or middle of the road cinema, identified with Hrishikesh Mukherjee (part of Sen’s circle in Calcutta) and Basu Chatterjee. But a more popular and organic engagement with the festering unrest of the times was the angry young man persona of Bachchan’s major box-office hits written by Salim Javed in the 1970s. Bhuvan Shome was where the twain co-incidentally met.

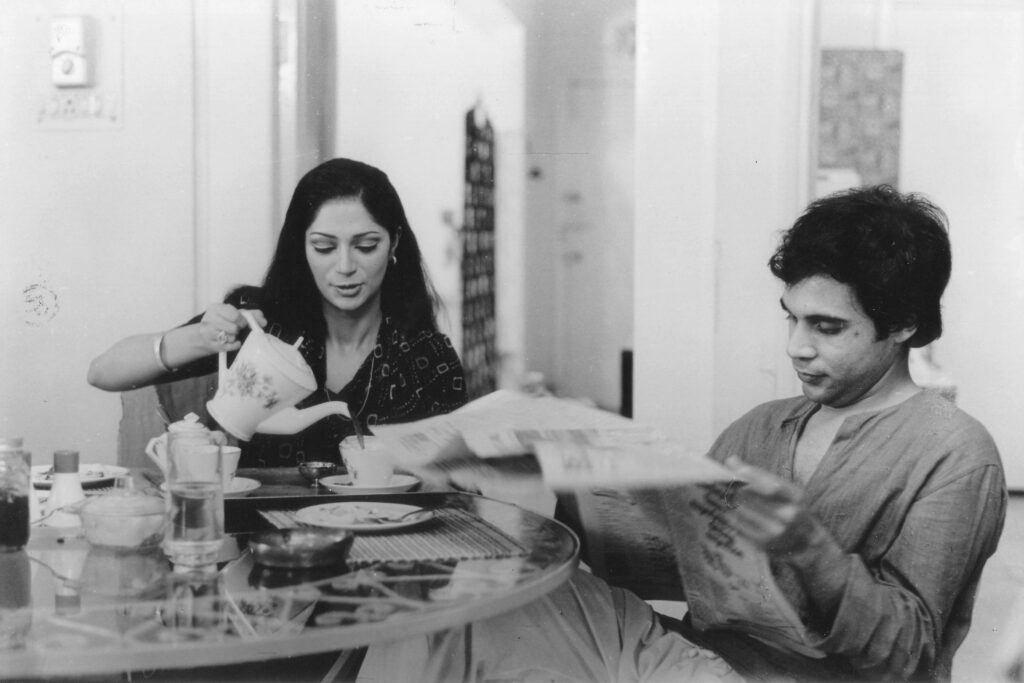

A charming, chuckle-aloud comedy about a big bureaucrat and an effervescent village girl, Bhuvan Shome is one of the first Indian films to make interesting use of animation, freeze frames, real world footage and unexpected use of sound, such as a steam engine’s hiss for the railway bureaucrat’s laugh. The film was both a box-office and critical success, although Sen’s contemporary Satyajit Ray, otherwise complimentary about Sen, described the film as formulaic: “Big bad bureaucrat tamed by rustic belle.”

Sen’s debut film Raat Bhore (The Dawn) was released in 1955—the same year that Satyajit Ray released Pather Panchali, which brought Indian cinema a degree of international acclaim it had never received earlier, and Ritwik Ghatak released Ajantrik, his second film but the first Ghatak film to release commercially. Sen directed 27 features, 14 shorts, and five documentaries in a 47-year-career, his last feature to release being Amar Bhuban in 2002. Six feature films were in Hindi, one in Telugu (Oka Oori Katha, 1977), one in Odiya (Matira Manisha, 1966).

Memories of the famine, and Naxalbari

Sen was not proud of his debut Raat Bhore although his hero was the superstar Uttam Kumar; in his book Montage, he called it “the biggest of all big disasters”. Nor was he proud of his second film Nil Akasher Nichey (1958) about the friendship between a Chinese street vendor in 1930s Calcutta and an affluent housewife who supports the national movement, a bhadramahila, who influences him to go back home and join the imminent revolution in China. [“It was over sentimental, technically poor, visually unsatisfying,” Sen wrote in Montage.] It now has a place in Indian film history for another reason—Nil Akasher Nichey is often named as the first Indian film to be banned after Independence during the Chinese invasion of India in 1962.

Sen’s third film Baishey Sravana, the first film in his career that he is unembarrassed by, blended two events that left an everlasting impression on his life. The death of Rabindranath Tagore in 1941, and the famine of 1943. The film’s title refers to the date 7 August 1941, or 22 Srabon on the Bengali calendar, the day Tagore passed. The story is about a couple, and how the Bengal famine kills the love and the humanity between them.

Indeed, Sen’s cinema never lost consciousness of the political, economic and the historical moment, of the larger currents shaping the lives of people at any point in time. He revisited the Bengal famine and the looming shadow of starvation and desperate privation again and again in his career, most ostensibly in Akaler Sandhaney (In Search of Famine), 1980, and to a subtler extent in films like Kharij (1982).

He is often called a political filmmaker, a nomenclature that was probably bestowed on Sen because he never stopped engaging with the contemporary developments of his time. He made arguably only the one period film—Mrigaya—unlike Ray, who excelled at the format and made Charulata, Ghare Baire, Shatranj ke Khiladi and the Apu Trilogy. But this may in fact be a reductive label, because his work was no less artistic or moving or funny for addressing the political economy of his time.

“In the trinity of Ray-Ghatak-Sen that defines Indian cinema, Ray was the artist, a brilliant disciplined mind,” said Adoor Gopalakrishnan, the Malayalam language auteur whose meditative, languorous sequences have led some critics to call him Ray’s legatee in Indian cinema. “He chose film as his medium but he could easily have chosen any other art form. Ghatak was highly theatrical, both in his personal life and his work. He was highly original in the way he raised melodrama to a high art form. Mrinal da had the qualities of both of them. Some people call him political and he did have a brief political phase, but he came out of it soon. A political film is defined by certainty. The beginning is the end because it is all a message. But Mrinal da has a lot of questions in his work. The opposite of certainty.”

“Sen had this ability to inject an existential situation that is almost commonplace with a quirky humour that turns every character into an unpredictable, therefore, rounded being,” said Naveen Kishore, poet and publisher of Seagull Books, who published three of Sen’s screenplays, and a book of Sen’s essays and interviews called Montage. “The imperfections are vital. Everyone is capable of both ‘letting themselves and therefore others down and equally capable of rising to the occasion.”

Some people call him [Sen] political and he did have a brief political phase, but he came out of it soon. A political film is defined by certainty. The beginning is the end because it is all a message. But Mrinal da has a lot of questions in his work. The opposite of certainty”

Adoor Gopalakrishnan, filmmaker

The introspective Leftist

Indeed, Sen retained a frankly astonishing ability to introspect on the shortcomings of the Leftist movement and its political victories in Bengal. In films such as Padatik, Ek Din Pratidin and Kharij, he visits the moral hypocrisy and gender-blindness that prevailed in Bengal in the heyday of the Left Front government.

Padatik is the story of a young, Naxal-type leader who goes into hiding in the home of an affluent woman, a successful corporate employee who sympathises with the Leftist cause. The exchange between this woman, played by the actor and TV show host Simi Garewal, and the young man played by Dhritiman Chatterjee, reveals how narrow and patronising the Communist idealist’s mind can sometimes be.

Ek Din Pratidin (And Quiet Rolls the Dawn), 1979, tells the story of a middle-class Calcutta family whose elder daughter, the only one in the family with a job, does not return one night. Over the course of the night, the family envisages many scenarios for her absence but the one that terrifies them the most is obvious: what if she has eloped with a lover or is spending time with a man? How will they face the social shame? From their conversation it is clear that it would be a relief to them if she were found dead. At the film’s end, the daughter returns but we are not told where she was. It is widely considered Sen’s finest and an outstanding film by any measure.

In Kharij (1982), a young servant boy dies at the elegant south Calcutta home of an aspirational upper middle-class couple played by Mamata Shankar and Anjan Dutt. Palan, the young servant, is the same age as their son. The boy’s father tells the couple that he will at least get two meals a day and some money working in their house. Here is the echo of the hunger that continued to stalk the countryside and Sen’s conscience. The boy has to sleep inside the kitchen, although the house has plenty of rooms. One morning, the boy is dead. The post-mortem states carbon monoxide poisoning, suggesting the kitchen fumes are to blame. Yet at the end, the dead boy’s father departs without a fuss, raising his hands into a namaskar and not to strike the guilt-stricken husband. A devastating indictment of how nothing happens to the culpable if they belong to a privileged class in India.

And Sen would turn this same sharp gaze on himself. Consider this interview about his celebrated film Akaler Sandhaney (In Search of Famine) where a film crew “invades” (Sen’s word) rural Bengal for a film about the 1943 famine: “We put the poverty and the whole thing into the cans. And then we go back to our places. And then the films will be shown to different areas, even to the foreign countries where it would perhaps bag an award. It did, eventually. And then I will forget all about these people. But if you ask me this question whether I got involved or not during the shooting, I would say of course I did. I developed a respect for the circumstances in which these people live. But after that, what happens? After that, I keep on telling the stories very respectfully but I forget all about them. In a way, we exploit these situations.”

The unexpected returns of real-world footage

In 1969 when Bhuvan Shome had released and become a hit, two producers from Bombay came to Calcutta, put up at the Grand hotel and waited to meet Sen with offers to produce a film if he directed it in the Bhuvan Shome style. “I refused… And that was a terrible time for Calcutta, 1969-70. I was arrested. There were killings and murders around every other corner. I could hardly step out of the house. It was the worst of times for the country and yet the best of times for me to carry out experiments like this.”

“Personally, Mrinal da never stopped believing in the ideals of Communism,” Gopalakrishnan said, on the phone. “He used to say, I’m a private Marxist. How simply he lived! It is hard to believe that a director who has been on the jury of every major European festival lived like that. He would joke, ‘I see the lifestyle of a filmmaker and I can tell what quality of film he will make.”

Sen made four films about the turmoil in Bengal between 1970 and 1974: Interview, Calcutta 71, Padatik, Chorus. In a couple of these, he used real footage of the protests, speeches and rallies in Calcutta that he shot out and about in the furious city, the documentary approach was new to feature films in India at the time. Of these, Calcutta 71 proved to be a hit at the box-office, but the reason for its success was not cinematic excellence, Sen wrote.

The footage of real political meetings in Calcutta 71 comprised recordings of several young men who had been killed or had disappeared by the time the film released as a consequence of the murderous crackdown by the state. Many people came to the theatres again and again to see their murdered brother, son, friend, lover amid the faces in the demonstrations. Here on the screen, they were alive again, walking protesting as if they were still out there somewhere on the streets of Calcutta.

A love for small budgets and paying everyone their professional due

Although he is less well-known outside Bengal, Sen was a regular on the global film festival circuit, not just in Europe but also Latin America and Russia. He is the first Indian to be invited to the Cannes Film Festival jury, serving in 1982.

Sen is a pioneer of the use of existing and real-world footage in feature films, a technique he used to great effect in his Calcutta trilogy—Calcutta 71, Padatik and Chorus. In Calcutta 71, he also used footage from his own feature, Interview.

“Mrinal Sen’s legacy is Indian cinema is his fearless experimentation,” said Srijit Mukherji, director of Padatik, the forthcoming biopic on Mrinal Sen, and winner of several National Awards for direction and screenplay. “In terms of shot-taking, edit patterns, use of noise, freeze frames, breaking the fourth wall, use of real world footage, he established a style of filmmaking that was absolutely distinct from the other great icon of Indian cinema, Satyajit Ray. And he did this while he was struggling to find his own voice in cinema. Confronting the constraints that have plagued Bengali cinema for long—the lack of funding and equipment.”

Aside from Mukherji’s film, two more films are in production to mark Sen’s centenary: a sequel to Kharij tentatively titled Palan, and a remake of Chalchitra (1981).

Sen’s resourcefulness with finding funding and his can-do confidence is reflected in his prolific and unusually multi-lingual output. He took pride in completing films in low budgets, and enjoyed returning money to producers.

In an interview to Punch magazine, his son Kunal said that this was a subject of ongoing disagreement between father and son. Kunal, an enthusiast and student of technology, told his father that larger budgets would enable him to work with more sophisticated technology, improving the quality of his work. But Sen was reluctant, he believed that when a film has a large budget, it becomes a capitalist project. More importantly for him, that he would become dependent on financiers.

And yet, a number of actors from the Hindi film industry came to work with him in Calcutta: these include Simi Garewal (Padatik) and Dimple Kapadia (Antareen), aside from the arthouse stars Smita Patil, Shabana Azmi, Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Shriram Lagoo, Nandita Das, as did two generations of Bengali star actors such as Soumitra Chatterjee, Madhabi Mukherjee, Aparna Sen, Mithun Chakrabarty.

The small budgets notwithstanding, the private Marxist treated his cast and crew with respect, affection and equity. In Bhuvan Shome, he insisted on paying Bachchan Rs 300 for his narration, though Bachchan had refused payment as that was his first professional assignment in cinema. “All of us are accepting payment,” Sen told him. “You cannot insult us like this. Take it professionally.” It is worth pointing out that Bachchan was not a superstar or even a star at the time, he was a young man working on his first film

All of us are accepting payment. You cannot insult us like this. Take it professionally”

Mrinal Sen to Amitabh Bachchan regarding his voiceover in Bhuvan Shome, for which he paid the debutante Bachchan Rs 300

On her website, Garewal writes, “Mrinal da was always concerned, that coming from Bollywood, I may not find the food and conditions appropriate and he extended himself to make me comfortable.”

“If a spot boy had an input, Mrinal da would listen to it. He might even incorporate it,” said Suhasini Mulay, winner of five National Awards—four for documentaries directed by her and one for acting. “That was the kind of open space his set was. It was very different from a Ray set, where everything was planned down to the last detail. And I think people were scared of Ray too. If you look at his filmography, you see Ray gradually taking over departments—music, camera, more. Mrinal da was also planned and knew what he wanted. But he thrived with an exchange of ideas.” Mulay first acted in film in a stellar turn in Bhuvan Shome. She assisted Ray on Jana Aranya (1976) and Sen on Mrigaya (1976).

But most moving, and perhaps most illustrative of Sen, the professional, is a memory from his memorial recounted by the critic Ina Puri. “Apart from the film actors, actresses and directors, there were many, many technicians, old and fragile, who had come from far to pay their last respects, sharing their memories of how generous he was with each and every member of the crew to those who would care to listen,” Puri has written. “The overwhelming feeling in that auditorium was not of grief but equally of amusement, as colleagues spoke of his humour and sense of fun. Quite befitting for the filmmaker who never compromised till the end and knew how to laugh at himself.”

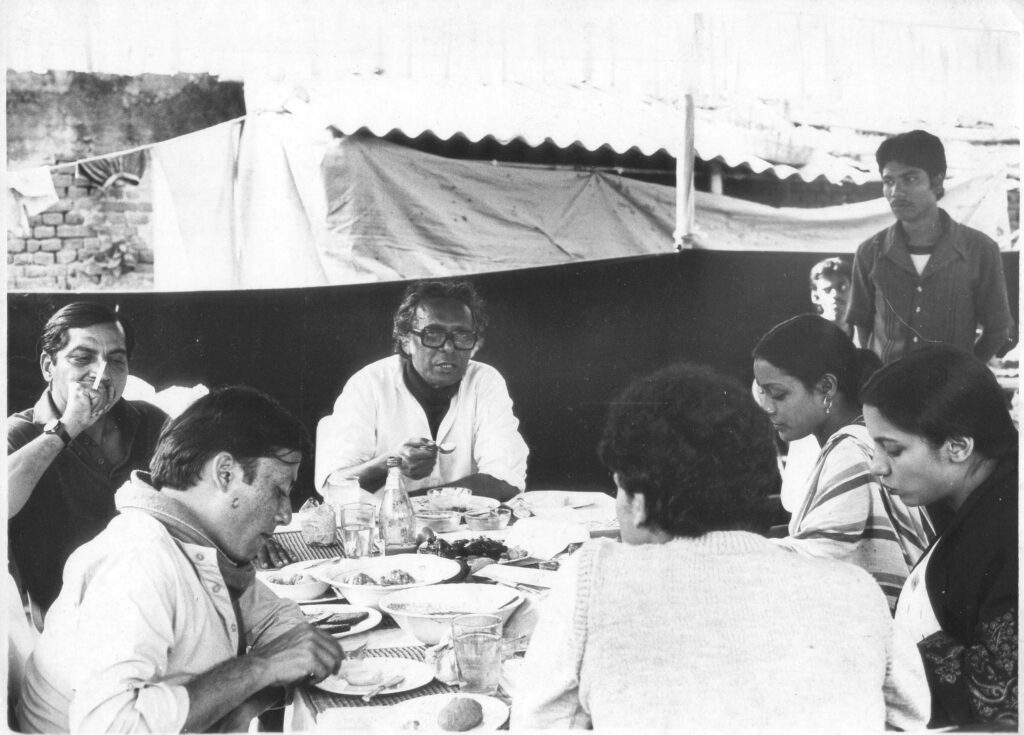

Mrinal Sen (centre), KK Mahajan (to Sen;s left), Pankaj Kapur (left most) eating together on the sets of Khandhar (The Ruins,1982). To Sen’s right is first, Sreela Majumdar and then Shabana Azmi. Image courtesy the Sen family collection.

My book The Day I Became a Runner offers an alternative history of the republic, from the late 1930s to the present moment, through the lives of 9 women athletes. It is available on Amazon and bookstores across India.