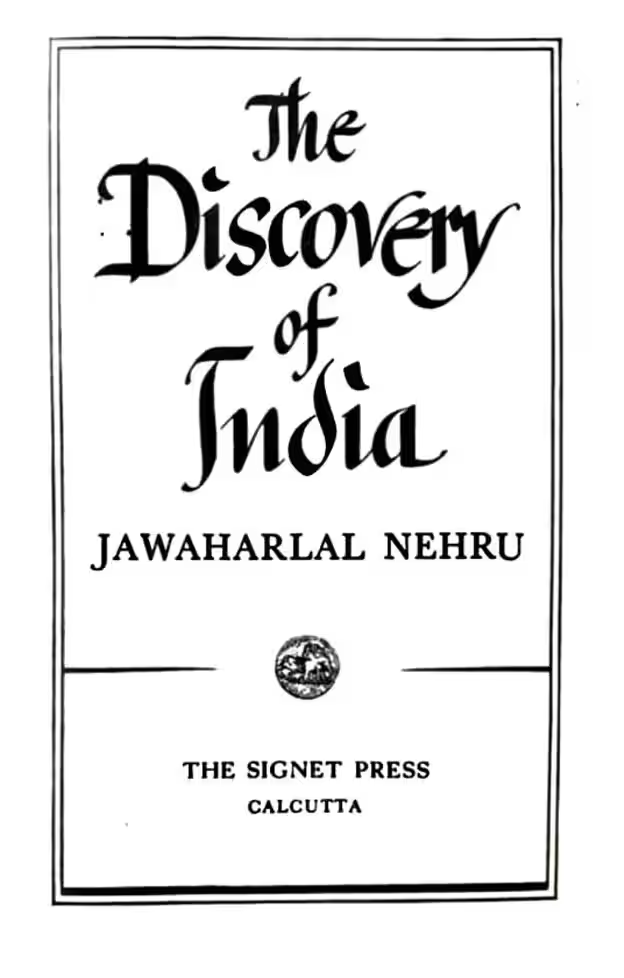

The Calcutta publisher that published the first edition of Jawaharlal Nehru’s The Discovery of India in 1946, is known for outstanding cover art and illustration, clean layouts, stylish typefaces

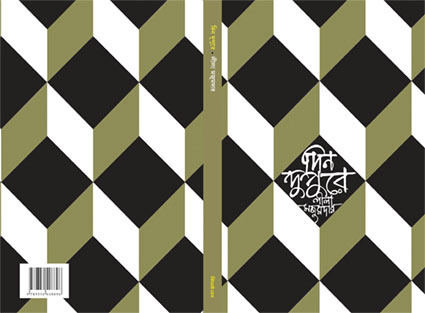

Satyajit Ray’s cover design for Leela Majumdar’s Din Dupure (In Broad Daylight), published by Signet Press. The pattern of alternate shades of diamonds suggests the patterns the afternoon light leaves on the floor, making its way through the drawn curtains, no?

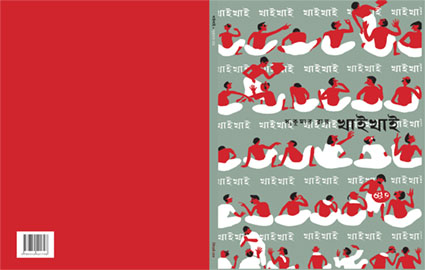

On October 30, 1943, when it was announced that the nonsense verse maestro Sukumar Roy’s poem Khai Khai (Translated title: Nom Nom) was going to be published as a separate volume by a new publishing house called Signet, he was already dead 20 years. It was the first time Roy’s work was published outside of his family’s press U Ray and Sons, and the ambitious Signet would change the image and practices of Calcutta publishing itself.

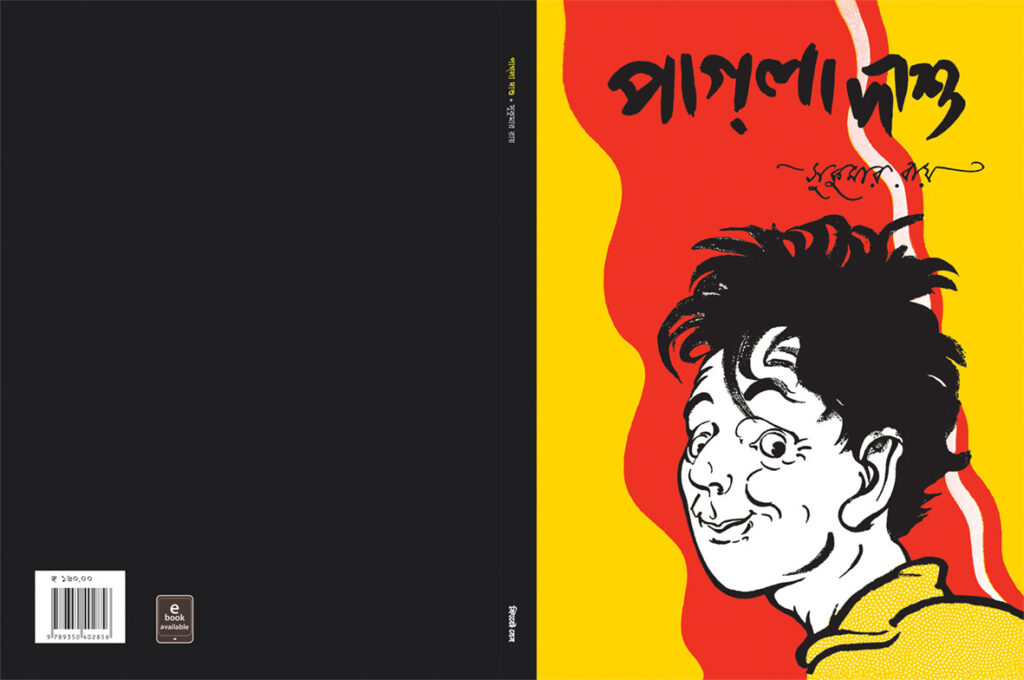

Roy himself was a phenomenon—his nonsense verse is considered to be on par with Lewis Carrol’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Eurocentric world’s idea of the finest in mock verse. In fact with this book, Signet launched a third phenomenon in the world of art and letters: Sukumar Roy’s son Satyajit (who spelt his family name Ray) designed the cover and illustrated some of the inside pages of Khai Khai, more than a decade before he debuted as a filmmaker with Pather Panchali.

Eighty years later, at the 46th edition of the Kolkata international book fair, Khai Khai—still in print in its original design: a grey cover with brahmins in dhutis sitting down to eat, in a handsome comic-book sized edition—was so popular that the Signet Press stall had run out of copies before the fair was over.

Before Signet, it would not be wrong to make the generalisation that Calcutta publishing was dominated by family and community-owned presses that published mostly religious pamphlets and books, and some self-published books characterised by plain beige covers without art, little distinction in typefaces or any thought that went into the layout of pages and binding. Even the mighty Rabindranath Tagore self-published several of his first volumes of poetry at the Brahmo Samaj printing press—a community press that printed leaflets for the Samaj, and self-published some books by members with writerly ambitions.

The exception to this generalisation was perhaps Visva Bharati University’s press where Tagore had the stalwart of the Bengal School of Art, Nandalal Bose, illustrate the Bengali textbook Sahaj Path (Translation: Easy Reading) with woodcuts and sketches. Visva Bharati’s plain beige-orange covers, a standard in Bengali publishing of the time, also boasted elegant typography. But it was Signet that lifted Bengali publishing, and it would not be wrong to say publishing in India, by several degrees qualitatively. And given the backgrounds of its two founders—advertising and journalism—this was unsurprising.

An Unlikely Duo-in-Law

Dilip Kumar Gupta, known as DK in Calcutta advertising and publishing circles, worked at the agency DJ Keymer and Co Ltd and is often considered the sole force behind Signet. But an equal founder was his mother-in-law, the feisty feminist writer, journalist, and translator Nilima Guha Thakurta, an essay in the Ananda Bazaar Patrika’s Sunday supplement recounted in 2022. She headed Ananda Bazaar Patrika’s ‘Narir Katha’ (women’s issues) section, and also wrote for it under the pen name Sanghamitra. In the 1920s, she had caused a stir in Allahabad, and indeed Calcutta’s Bengali society, when she left her first husband because she had fallen in love with the man who would be her second husband, Prabhucharan Guha Thakurta. He was a star in the world of advertising and DK was one of many young people who admired him.

“(Signet brought) flawless spelling, outstanding cover art, incomparable illustration, robust binding at a reasonable price,” the writer Leela Majumdar was quoted as saying in an excellent feature in AnandaBajaar Patrika in Bengali. Majumdar’s own trailblazing career as a children’s books and science-fiction writer, would receive a second wind from Signet, much like her cousin Sukumar Roy. Like him, she too had primarily published in the family’s U Ray and Sons press, and the magazine Sandesh before Signet. The brick-red cover her nephew Ray designed for Podi Pishir Bormi Baksho, her best-known work, is a delight—a fierce snake drawn in the South-East Asian tradition of dragon-like creatures

Signet was born in 1943, the year Nilima Debi lost her beloved husband to a protracted illness, decided to get her daughter Nandini married to DK, and sold the shares and life insurance she inherited to start a publishing house with DK.

DK had, for long, wanted to start a publishing house that incorporated the ideas and aesthetic that his work in the British advertising firm had introduced him to, and the marriage and the formal kinship it brought with Guha Thakurta enabled the fruition of this dream. The publishing firm functioned out of their joint family home on Calcutta’s Elgin Road.

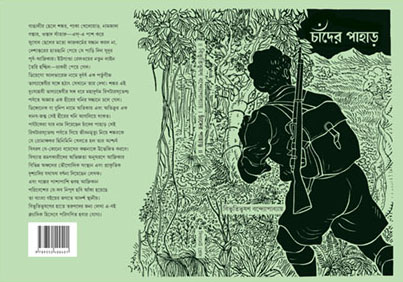

Guha Thakurta dived into work with her son-in-law, a partnership that led to a brilliant near uninterrupted run until the late 1960s. They gave a new home to beloved writers such as Sukumar Roy and Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay (the author of the books that became Pather Panchali on screen), they published new names such as the novelist and poet Sunil Gangopadhyay, the poets Jibananda Das, Sankho Ghosh and Bishnu De, considered the greatest writers in modern Bengali after Tagore.

Very occasionally, Signet also published in English. Early in 1946, Vijayalakshmi Pandit called up Guha Thakurta to ask if they would be interested in a manuscript her brother had completed in prison called The Discovery of India. Jawaharlal Nehru’s last and best-known book was first published by Signet with illustrations by Satyajit Ray in 1946. Signet also published the photographer Sunil Janah’s first book, titled The Second Creature, designed by Satyajit Ray.

“(Signet brought) flawless spelling, outstanding cover art, incomparable illustration, robust binding at a reasonable price,” the writer and memoirist Leela Majumdar has been quoted as saying. Majumdar’s own trailblazing career as a children’s books and science-fiction writer, would receive a second wind from Signet, much like her cousin Sukumar Roy. Like him, she too had primarily published in the family’s U Ray and Sons press, and the magazine Sandesh before Signet. The brick-red cover her nephew Ray designed for Podi Pishir Bormi Baksho, her best-known work, is a delight—a fierce snake drawn in the South-East Asian tradition of dragon-like creatures.

Ray was a colleague of DK’s at DJ Keymer; he had trained in art at Shantiniketan’s Kala Bhavan and came on board as a designer right at the beginning. Arguably, it was his work at Signet that shaped his path to filmmaking. He illustrated a number of books by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhya including Aam Aantir Bhepu, the story of the brother and sister in a village in Bengal that became Pather Panchali on screen. He realised the cinematic quality of Bandyopadhyay’s story of a village steeped in tradition facing the inevitable incursions of modernity, of the train piercing into the still countryside, when working on the drawings.

The Rebirth

After the late 1960s, Signet’s pace slowed. Guha Thakurta and DK were both ageing, and were no longer able to work like they did, burning the candle at both ends. For DK, this meant working a day job in advertising and for Guha Thakurta, running the household along with her daughter Nandini, and her duties as a grandmother.

“My father and grandmother would work all night on Signet’s books,” said Indrani Dutt, DK’s daughter and Guha Thakurta’s granddaughter, who wrote the book A Calcutta Publisher’s Daughter. “They used to take medicine so that they don’t feel sleepy. It was as if they were on a mission to take good Bengali writing into the hands of readers.”

In 1975, Signet Press stopped publishing new books. DK died in June 1977, and five years later, his indefatigable mother-in-law expired. Perhaps it was the fact that the prices were always reasonable though the production was of a high quality. More than anything else, it showed Signet was a passion project rather than a commercial enterprise, even if the aesthetic and energy came partially from international advertising. Until 2010, all that remained of Signet was the shop in the College Street area of Kolkata.

And of course, the legacy.

“Signet, for those of us who grew into publishing straddling different technologies, the press was an inheritance that inhabited our thoughts,” wrote Naveen Kishore, publisher of Seagull Books, the 40-year-old international publishing house known for its cerebral list and stunning book covers. “The word virasat sums it up! Not just for their beautiful covers in an era where the aesthetics of book publishing were not as ‘aware’ as they are now, but also for their inner page designs, the setting of their pages, the text being allowed to breathe. Their content signalled intent. Particularly their hugely supportive and nurturing role in publishing poetry. There is a direct lineage here with the modern-day Bengali publisher being very positive about poetry.”

In 2010, Ananda publishers, a publishing house in Bengali and the publisher of Ray’s Feluda books among others, asked to buy Signet Press from Nandini Gupta, DK’s widow and Guha Thakurta’s daughter. She was growing old, and had catalogued the list of Signet publications as best as she could. The family did not have the means to continue the work of Signet but she was reluctant to leave the legacy of her husband and mother untended. Would Ananda be interested?

“For us, it was like being entrusted with Indian publishing’s greatest heritage,” said Subir Mitra, director of Ananda Publishers. “We sat and worked with her to first locate every book she had listed as a Signet publication. A xerox copy was not good enough. We visited archives, people’s homes to locate actual copies because we wanted to republish Signet books exactly in the way they had been published—not just the same covers and design, but the same size and if possible, the same quality of paper.”

Aside from Signet’s substantial backlist of 300-plus books, Ananda also publishes new titles in poetry, essays and food/cooking books under this imprint to give it a distinct identity.

At the annual Kolkata book fair, billed as the biggest book fair in Asia, they maintain two stalls—one for Ananda, and a separate smaller one for Signet Press. From the signage outside, you would not guess that Signet has a connection with Ananda.

“Signet came much before us, and its work and legacy is unique. We want to maintain that in every which way,” said Ratul Bandyopadhyay, editor-in-chief, Ananda Publishers.

This feature was originally published on the website Moneycontrol in February 2023

1 comment for “How Satyajit Ray and 80-year-old Kolkata firm Signet Press changed publishing in India”