A figure leaps headlong onto the screen, fully armoured, face hooded by a helmet. Spears are sent clattering, sentries hurtle across the room, Bajirao and his lieutenant watch in surprise. We don’t know whether this is a man or a woman, friend or foe. Could this be Mastani?

The anticipation was nicely set up by the trailer for Bajirao Mastani, put out five months before the theatrical release. We see an unblinking Bajirao, drawing back his bow with a formidable creaking. Then we see Mastani, equally still of eye, and it is her arrow that alights with a terrific pop. Seconds later, we see Mastani cradling a child in one hand, thrusting savagely—and confidently—with a sword with the other.

In my favourite scene in the film, Mastani whips out her sword from its scabbard, caresses the blade with something between pride and love, and performs a little ballet with it. There is that little swoop of exaggeration to her movements: she is dancing with her sword now, Mastani the renowned warrior, dancer and poet. It is a terrific little sequence, and it comes after a horrible snub from her mother-in-law who calls her a “dancing girl”, even arranging for her to stay in their quarters.

I realised then that the film’s subtitle, “the love story of a warrior”, applies equally to both title characters, Bajirao and Mastani. They are both warriors at heart. Deepika Padukone’s Mastani, who strums her harp as coolly as other cinematic tough guys suck on toothpicks, is a rendition of the virangana—the classic Indian archetype of the woman who rides into battle for the sake of her country and people. The iconic image is of a woman riding a horse, sword aloft. She is a woman of courage—the physical kind necessary to go out and fight.

“Aakhir yoddha hoon, thokar patthar se bhi laga toh haath talwar pakadta hai (I am a warrior, after all… even if I stumble on a stone, my hand grasps my sword),” Mastani tells Bajirao’s brother. Over and over, she displays the same cut and thrust in her dialogue-baazi (for it is this old-fashioned verbal grandstanding that the film swaggers forward on). In his review on his blog, Hindu film critic Baradwaj Rangan wrote these are the sort of lines an action hero would get.

It is an important attribute. Not only for Mastani, but the virangana in general. She speaks her mind. She is a fighter not only on the battlefield but also in everyday life, calling out prejudices and hypocrisies.

In her “warrior queen” avatar, she is truly a leader of her people, marshalling her troops in battle, challenging attitudes in society. She is that unlikely creature both feminists and video game-makers love: she knows her dishoom, she speaks her mind, she does her own thing.

2015 saw a number of prominent films—not only in Mumbai—starring women in the action mould. In SS Rajamouli’s Baahubali, Tamannaah plays Avanthika, a committed soldier of an underground rebel movement in the kingdom of Mahishmati, ruled by the vainglorious king Bhallaldeva. Baahubali’s trailer betrayed no hint of Avanthika’s martial skills, depicting her as a dreamlike, apsara-like beauty. But in the movie, the hero Shivu is shown her greeting an intruder with a spray of arrows. He crouches behind a tree, watching Avanthika. Her hair is pulled back from her face, her backpack is a quiver of arrows, her ears are unadorned with earrings; she climbs trees and jumps from them with the ease of a wood sprite. When the leader of the movement fixes a date to assassinate the king, it is Avanthika he picks for the job.

Also in Baahubali, Ramya Krishnan plays the heroic and just Sivagami, queen of the kingdom, who is not afraid of brandishing her sword—or leaving behind a trail of blood. She also effectively takes over the reins of the kingdom.

NH10 and Drishyam had intriguing takes on the virangana motif, though clearly on a different register from the sword-waving avatar. There’s the recent Jai Gangajal, in which Priyanka Chopra is the police chief of a dusty, badly-behaved town, the forthcoming Akira which has Sonakshi Sinha as the main action hero and, intriguingly, Vishal Bhardwaj’s Rangoon, where Kangana Ranaut is reported to be playing a character based on the real-life stunt queen Mary Ann Evans, known as “Fearless Nadia”.

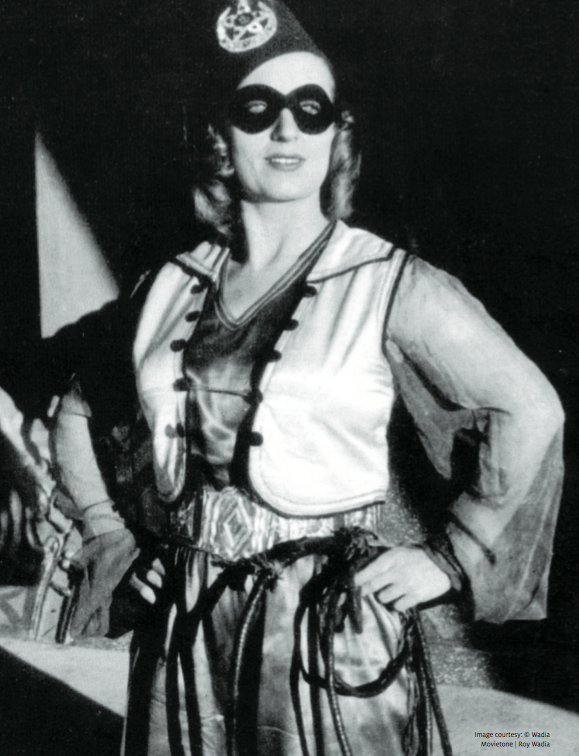

Maryanne Evans, better known by her screen persona as Fearless Nadia

Nadia is the boss lady of Hindi film viranganas, the star who left such a mark that she has, in fact, become synonymous with the persona on screen. Her iconography has, in turn, reshaped the persona of the “warrior queen”.

Nadia, however, was a B-film star—the stunt film was very much a B-film genre— while the movies mentioned above are all lush, A-grade confections. How has the virangana evolved since the 1930s—from Nadia to Mastani to Meera from NH10 to, well, Nadia herself?

Each time a Bollywood actress mounts a horse and holds aloft a sword, a dutiful feature writer reminds us of Hema Malini in, and as, Razia Sultan. The ambitious, extravagant 1983 film by Kamal Amrohi was based on the 13th-century ruler of the Delhi Sultanate. The story will usually go on to Aishwarya Rai as the female lead in Ashutosh Gowariker’s Jodhaa Akbar—though she only had a couple of nice sword-fighting sequences. (There is also Kaurwaki, played by Kareena Kapoor in Asoka—the free-spirited, eyeliner-loving princess of Kalinga who spends most of the film making eyes at the emperor but fights spiritedly in the climactic battle.)

Less well remembered is the 1953 film Jhansi ki Rani, made by the Parsi stage actor and director Sohrab Modi, starring his wife Mehtab in the title role. The film, like Razia Sultan, bombed at the box office. But for some reason it has far less recall value than Hema Malini’s project. There has been talk about another film on Rani Laxmibai for years now.

But the virangana goes back much farther than Hindi cinema. In fact, versions of the viranganacan be found in Hindu mythology. Durga, the ten-armed, fully-loaded goddess riding a lion, who takes on the asura to protect her children and herself, is perhaps a predecessor to the “daughter of the kingdom”. The academic Kathryn Hansen, in an essay in the Economic and Political Weekly in 1988, noted that the virangana stands as an “alternate paradigm” to the two most established female motifs in Indian narratives— that of the devoted wife and the powerful mother. She is a “valiant fighter who distinguishes herself in warfare”. She dresses in male clothes, rides a horse and adopts male symbols such as a sword. Her approach to life is Do-It-Yourself: if she wants something, she sets about getting it herself.

Hema Malini in the title role of Razia Sultan (1983)

Hansen argued that the virangana appears prominently in folk forms such as tamasha and nautanki, where stories are drawn not only from history but also from local legends and press reports. Quite naturally, folk theatres extended the characterisation of the virangana from a persona defined by physical bravery on the battlefield to a figure of moral conviction in the context of protecting “family honour and sexual purity”. We see this vividly in nautanki classics such as the tale of Shirin-Farhad, where the princess Shirin kills herself when her low-born admirer Farhad is tricked into committing suicide.

Given the kinship between folk theatres and early Hindi cinema, the virangana made her way to Bombay fairly quickly. The conventional brave girl heroine appeared in silent films such as Sati Veermat (1923), Devi Ahalyabai (1925) and Sultana Chandbibi (1932). But this was extended in a rather racy direction with the advent of the stunt film, inspired by the Hollywood hits of the 1910s and ’20s. A series of films with titles such as A Fair Warrior (1927), Female Feat (1929),Valiant Angel (Chitod ki Virangana, 1931), Stree Shakti (The Super Sex, 1932), Daring Damsel (Azad Abla, 1933), The Amazon (Dilruba Daku, 1933) and Lady Cavalier (Ratna Lutari, 1934) were released.

The Bombay stunt genre really hit its stride in the 1930s and ’40s with the phenomenal Mary Ann Evans, a half-British, half-Greek girl born in Australia. Trained as a dancer, she started her career in dance and vaudeville, and first appeared in a small role in an Arabian Nights-themed silent film called Laal-e-Yaman. Her first lead role came in 1935 in JBH Wadia’s Hunterwali, itself a remake of the smash hit Dilruba Daku, which had starred the Bengali actress Padma as a masked, horse-riding avenger. Thus began the whip-cracking, galloping success (literally and metaphorically) of “Fearless” Nadia, in a series of films with swashbuckling names such as Miss Frontier Mail, Lutaru Lalna (1938), Punjab Mail (1939), Diamond Queen (1940), Miss Hunterwali ki Beti (1943) and a host of others.

Nadia was neither the first heroine, nor the only one to be beating people up back then. In 1936 alone, aside from Miss Frontier Mail, there was Mehboob Khan’s Deccan Queen, V Shantaram’s Amar Jyoti starring Durga Khote and Bambai ki Billi starring the superstar of the silent era, Sulochana. In her analysis of female stardom in Hindi cinema, film scholar Neepa Majumdar has argued that the Jewish Sulochana was the anti-Nadia, being a serious dramatic actress of sophistication and repute. Such was the success of the stunt genre that even actresses and directors who took their craft seriously tried their hand at it. Take Amar Jyoti: Shantaram had a real artistic calling, and this movie was perhaps the first A-grade film to feature the heroine as badass.

Interest in virangana movies peaked in the first few decades of the 20th century, wrote the academic Rosie Thomas, as nationalist sentiment soared in the country and British censorship made direct references to the struggle impossible. The yearning for seizing independence expressed itself in the form of a fighting-fit body. A physical culture was taking shape in pockets of India.

So phenomenal was Nadia’s success that she became, in a sense, the brand name for thevirangana genre. Thomas noted how Nadia belts, matchboxes, playing cards and even whips appeared in the market. A much-cited quote by the actor and playwright Girish Karnad illustrates this rather well: “The single-most memorable sound of my childhood is the clarion call of Hey-y-y as Fearless Nadia, regal upon her horse, her hand raised defiantly in the air, rode down upon the bad guys. To us school kids of the mid-forties, Fearless Nadia meant courage, strength, idealism.”

Deepika Padukone plays Mastani Bai, a warrior princess and poet, in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Bajirao Mastani

The stunt genre might appear a completely separate thing from a historical film such as Bajirao Mastani. But in fact there is a straight line that can be drawn from the B-grade stunt films of the 1930s and ’40s to the posh period pieces that our sword highnesses now come wrapped in—and other sub-genres of female action films such as the revenge drama and the female cop movie.

The Nadia films embodied a virangana who was a thoroughly modern, confident woman—she spoke her mind, had no patience with badly-behaved men, dressed sexy, was comfortable with technology and kicked ass with élan. She was frequently seen driving a car or riding her horse. Both became much-loved accessories to her persona: the car was known as Rolls Royce ka betaand her horse, Punjab ka beta.

Thomas has noted four characteristic features of the Nadia virangana. Her physical presence was an important part of the image. Second, she cross-dressed. Third, she had sexual agency. And, most interesting of all, Nadia appeared not only when force was required, but when moral order needed to be restored.

Stunts offered an excellent avenue to explore the physicality of the virangana. As such, these films emphasised her physical attributes: a certain manner and degree of bodily display was necessary. Thomas described Nadia’s appearance in Hunterwali thus: “…she roamed the countryside on horseback sporting hotpants, big bosom and bare white thighs, and when she wasn’t swinging from chandeliers, kicking or whipping men, she was righting wrongs with her bare fists and an imperious scowl. By the time Nadia hitched up her sari and cracked her whip in the third reel, declaring ‘Aaj se main Hunterwali hoon’, the audience was cheering.”

Still, a reputation for low-brow, cheap thrills clung to the stunt movie. As Majumdar wrote in her influential book, Wanted Cultured Ladies Only, it wasn’t so much a “genre of ill-repute”, as a “genre of no consequence”. The Nadia films were especially popular with the “chavanni audience”, Shyam Benegal told me over the course of a telephone conversation, which is to say the front-benchers, the millmen, the blue-collar migrant workers. “And the tent-wala audience in the villages and small towns. I saw many Nadia films in these,” he remembered.

The Bombay stunt films and their stars were largely ignored by the press and the cognoscenti—perhaps due to the class aspect—which is likely why almost none of these films survive today. Miss Frontier Mail (1936), Diamond Queen (1940) and Muqabla (1942) are the only Nadia films that have been preserved in their entirety. (Muqabla and a much later film, Baghdad ka Jadu from 1956, are now available on YouTube.) None of the stunt films of her predecessors, or even her contemporaries, has survived, with the exception of Amar Jyoti.

It was really only in 1993 that Nadia was rediscovered, when the late documentary filmmaker Riyad Vinci Wadia’s Fearless: The Hunterwali Story was released. The film captured international attention. As with most rediscoveries, Nadia returned wrapped in layers of analysis that her directors may or may not have originally intended, or liked. She has been reclaimed as a feminist, and her films read as documents of “agency” and other terms beloved of anthropologists and cultural theorists.

Several papers and books analysing Nadia’s influence, chiefly by academics in Western universities, have been published after the documentary. A German writer, Dorothee Wenner, published a biography called Fearless Nadia: The True Story of Bollywood’s Original Stunt Queen. Rosie Thomas published an influential and highly cited essay on Nadia, “Not Quite Pearl White”, in 2005 in the volume Bollyworld: Popular Indian Cinema Through a Trans- National Lens. Historian Gyan Prakash’s Mumbai Fables carried a section on the superstardom of Nadia.

In spite of my fondness for the stunt virangana, I have reservations about calling the Nadia films feminist. The action is whistle-worthy, but these movies slip into an old chauvinistic trap—that a woman can only be a “hero” when she can hit like a man.

But there is something unreasonably fun about a woman with dishoom.

Ramya Krishnan as the tough-as-nails queen Sivagami in Baahubali

The Nadia brand of DIY heroine has inspired at least two tropes in A-list cinema: the revenge drama, such as Khoon Bhari Maang, Anjaam, Bandit Queen, Ek Hasina Thhi et al, and the female cop film such as Zakhmi Aurat, Phool Baney Angaarey and, more recently, Mardaani and Kahaani(the last named not really a cop film, but close enough). The two often overlap: Zakhmi Aurat is the revenge story of a female cop who was raped (Dimple Kapadia), while Kahaani features Vidya Balan in a memorable role as a wife seeking closure for her husband’s murder.

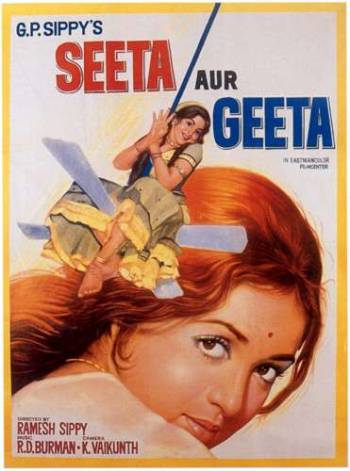

To my mind, the Nadia persona found its way even into comedies, most prominently in Ramesh Sippy’s Seeta aur Geeta.

The spirited Geeta slaps her mean aunt and whips her abusive uncle. In one sequence, she comes down the stairs, holding a belt like a whip, her trousers tucked into her boots. Nadia, again; and not just visually. Geeta’s function is primarily to restore the “moral order”. Over the phone, the film’s director Ramesh Sippy pointed out that the belt-cracking Geeta actually came from the film Ram Aur Shyam, featuring Dilip Kumar. “But I can understand why you would think Nadia, there is the similarity in the image. I have seen a couple of her films myself, and I enjoyed them,” he said.

Interestingly, Nadia played a double role in her 1942 film Muqabla, where she played two sisters—one docile and the other sassy.

The poster of Seeta aur Geeta featuring Hema Malini in a double-role. In 1942, Nadia had appeared in a double role in the film Muquabla

Its central concept is the same as that of Seeta aur Geeta. “It’s never as simple as how people remember what influenced them,” Rosie Thomas wrote to me in an email. “The point was that this image was culturally there and around to be plundered.”

Viewed through the Nadia lens, we see how both Mastani, who has more martial skill than political savvy, and Sivagami the consummate strategist and epitome of moral correctness, are both viranganas. Mastani is frank about her desire; when the king asks her what she wants before a public court, she names Bajirao. Avanthika, far more uptight than Mastani or Sivagami (and definitely Nadia), is a virangana too; her protest is motivated by the very moral position of restoring the kingdom to its rightful king. Sivagami does not cross-dress, but she splays out on the throne—feet up, back leaning on the arms of the seat; a postural smirk of sorts. She is also, more than anything, the mother of her people. In a striking sequence she breastfeeds her son and nephew while seated on the throne, listening to her ministers. It’s the sexiest power statement I have seen.

Nadia roamed a thoroughly modern landscape, drove a car, fought atop trains, worked out in itsy-bitsies in a gymnasium. She was a modern woman in a changing world shaped by technology. Indeed, a character remarks in Miss Frontier Mail, “You really are Miss 1936.” What we see in Bajirao Mastani and Baahubali is the Nadia brand of modern virangana, but in pre-modern stories.

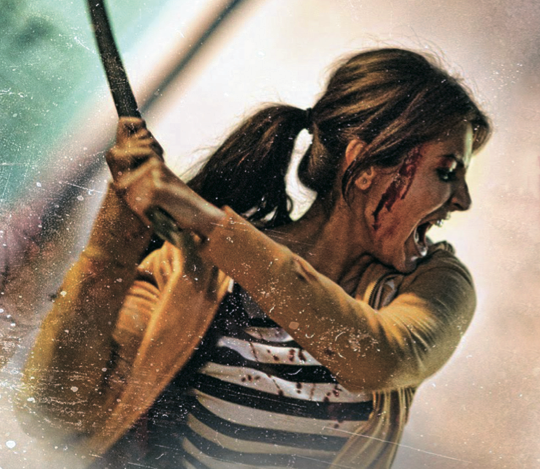

Anushka Sharma in NH10

The virangana also appeared in a more violent, unsettling avatar last year. In Navdeep Singh’sNH10, Anushka Sharma roams the highways to the south of Delhi with a rod. In the film, Meera (Sharma) and her husband Arjun (Neil Bhoopalam) are chased by two SUVs full of murderous men they had interrupted in the course of an “honour killing”. Arjun is first beaten, then bludgeoned to death. Meera, herself beaten, chased and now suddenly violently widowed, turns on the men as they turned on her: steely-jawed, focused on her job, determined to kill. By the end of the film, she is very quiet, very calm, very still. After she hits the last man with the rod, she lights a cigarette, takes a couple of long drags and then bludgeons him to death.

In many ways, NH10 follows the arc of the outlaw narrative—the Hunterwali story, where the female Robin Hood figure fights for justice. Meera seeks, and extracts, her own justice when she finds the police will not help her. But Meera is not fighting for her people. Early in the movie, in fact, she walks away from a girl begging for her help to escape the same assailants. Meera is fighting her own fight, seeking a private revenge.

Is this the form the virangana will take in a hyper-individualised world? Will Meera be caught on a phone camera, uploaded to the internet and become a viral video? Is this how the viranganawill ride today?

Perhaps the most tasty recent characterisation of the virangana is in Nishikant Kamat’s Hindi adaptation of the Malayalam film Drishyam, where the persona mutates to further shades of grey. The Nadia virangana is typically an outlaw. But here she is the face of the system. Tabu plays Inspector General Meera Deshmukh, chief antagonist to Ajay Devgn and his happy family. The narrative here cleverly inverts the intentions of protagonist and antagonist: Devgn, the hero, is covering up the murder of Tabu’s son, while Tabu is investigating him for the murder. As the police chief of Goa, she dresses in a crisp, body-hugging khaki uniform. She never raises a hand herself, but presides coolly over interrogations and orders her men to beat up suspects. It’s as if the action is projected bodily onto her colleagues and deputies.

Meera isn’t evil so much as misguided. Her son is missing, all the clues point in the direction of Devgn’s family, so she goes after him with the full force of the state police. She doesn’t spare even his younger daughter at interrogation. Ultimately, it is Meera’s husband, played by Rajat Kapoor, who intervenes to stop this nauseating violence.

Tabu’s Meera is not a bad person—in my view—but rather a powerful, attractive, slightly mad woman. She reminded me, in fact, of our best-known virangana in real life: Indira Gandhi. The same woman who as prime minister led her country through a difficult war. A stylish, admired leader known for her punishing work schedule and political acumen; a woman undone by her blind love for her family.

(This essay was first published in the Indian Quarterly magazine in July 2016.)