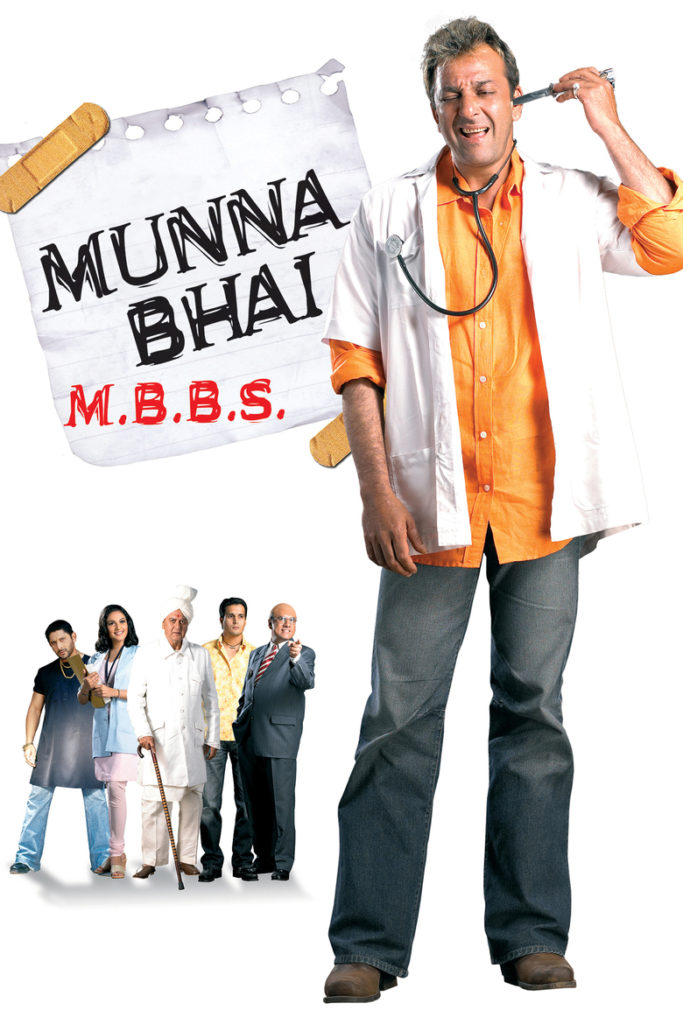

The documentary Placebo and the Hindi feature Munnabhai MBBS are companion pieces. Both feature outsiders entering the medical education system, and see our doctors as the products of a disturbing system

The documentary film Placebo was made in search of answers to an act of impulsive violence that its executor could not explain. Sahil Kumar, an MBBS student at the prestigious All India Institute of Medical Sciences smashed his hand through a window pane, damaging his nerves so badly that he needed two surgeries and eventually had to learn how to write with his other hand, the left hand. What brought on this moment? Sahil’s brother Abhay Kumar entered his hostel, at first for a period of three months, to understand what it was that drove his high-achieving brother to this act of savage self-harm. The months became a couple of years, a period in which no one at AIIMS realized that they had an outsider among them, a person who was not a student, or a teacher or a staffer. The film explores some of this unseeing, this numbness, that the hallowed corridors of a prestigious medical school inculcates among those who inhabit it. In one part, it tries also to explain a suicide in the college, prompted allegedly by casteism, but this is where the film was at its weakest I thought.

“In Julius Caesar, Brutus’ wife Portia commits suicide and Brutus says that everybody dies some day or the other. She died today. As I’ve gotten into this career [of being a doctor], I have become more and more stoic. I feel less afraid of death…I feel a kind of indifference,” says Sethi, one of the students Kumar follows in the film. Earlier in the film, Sethi says that his first ambition was to join AIIMS because he wanted to be part of the “elite”. Past the mid-point of the film, Abhay’s brother Sahil says that he felt “all the sadness of the world had crept up and filled into him” when he smashed his fist into the glass pane. By the end of the film, two of the four subjects the film follows have dropped out of medicine although they have collected their MBBS degrees.

Does medical education deaden students? Does the near impossibility of getting into medical school—the acceptance rate of AIIMS is less than 0.1 per cent while Harvard’s in 7 per cent—produce disdain for those who are not students of medicine? Is this mix of detachment and triumphalism what thickens into this waxy unchanging mask that many (most) doctors in India inhabit?

The companion piece to Placebo is the Hindi feature Munnabhai MBBS (2003). Here too, the title character is a trespasser in medical school, a don who has cheated his way in. The director Rajkumar Hirani, an accused in the MeToo movement, has spoken in interviews about how the idea for the film came from spending a lot of time in a medical college hostel, much like Kumar. In the first sequence set in the MBBS classroom, the dean tells the new batch of students that a patient should mean nothing more than a sick body to them. In response, Munna asks a question, one of the film’s most beloved moments: “When a patient is dying in the casualty ward, is it necessary to fill a form?” The comedy was broad and sentimental, but it was effective in depicting what a bit of conversation and thoughtfulness can achieve in treatment.

If cinema is a lens to understand society, then both these films tell you two things–why doctors evoke such dislike, and why they themselves appear dehumanized and alienated, out of love with the work they have spent so many years in training for. The terrific success of Munnabhai MBBS suggested that it had acknowledged a long-held public sentiment, offering the public the comfort that their antipathy was valid. After Munnabhai, the doctor has largely been a negative character in the Hindi film: in Andhadhun, the doctor is a mild-mannered organ trafficker who views human beings as suppliers of organs, in smaller Hindi films like Rahasya, Ankur Arora Murder Case and Waiting, doctors are murderers, racketeers, adulterers and megalomaniacs.

(The exception is the woman doctor, who is invariably a good, activist type, who bonds with her patients and laughs easily. Kareena Kapoor played the most memorable version of this doctor in Udta Punjab.)

But even before Munnabhai MBBS, the Hindi film doctor was alienated and disillusioned, sometimes corrupt too, headed for the un-empathy that Munnabhai explored. Perhaps the most famous doctor in Hindi film is Amitabh Bachchan’s Bhaskor Banerjee in Anand. When we see him first, he spends his evenings drinking and writing. He is already bored of his rich, hypochondriac patients, disillusioned with medical practice. Bachchan did another leading turn as doctor in the film Bemisal (1982). His friend played by Vinod Mehra is a gynaecologist. The gynaecologist is interested in making money, and performs abortions without permission and adequate care. When a patient dies and a criminal case looms, Bachhan’s character (a paediatrician) takes the blame and goes to jail because he owes his friend’s family a childhood debt. Already, one image of the doctor is a corrupt, criminal professional—the Mr Hyde to Dr Jekyll, who needs a childhood friend to save his skin. Incidentally, the doctor in Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella, is a medical doctor with an MD title.

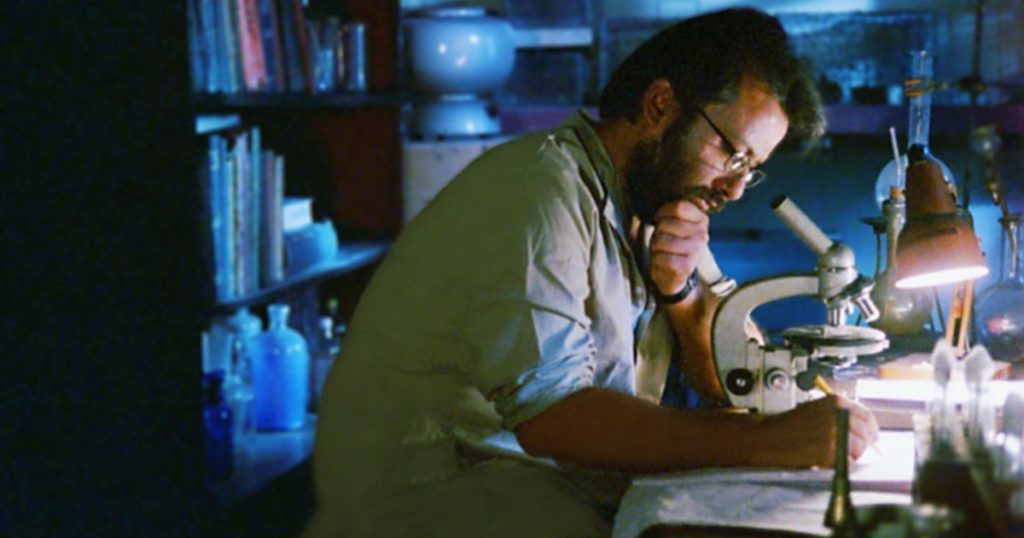

In Ek Doctor kii Maut, we see what happens to the good research- obsessed doctor in a petty establishment. The eponymous doctor finds a vaccine for leprosy, working on his own without institutional support, storing the vaccine in a test tube in his home refrigerator. But the petty government and jealous medical colleagues discredit his work, and later American doctors are credited with the discovery of a leprosy vaccine. The film told the real-life story of Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay who birthed a baby using in-vitro fertilisation (storing the embryo in his fridge at home). The baby he helped birth was born 67 days after the first test-tube baby in the world, but he was defeated by the pettiness of the Left Front government in Calcutta and viciousness of doctors’ lobby in Kolkata. In 2002, the Indian Council of Medical Research acknowledged him as the pioneer of IVF in India after Dr TC Anand Kumar, said to be the man behind India’s first test-tube baby, credited Dr Mukhopadhyay. In 2003, Kanupriya Didwania Agarwal, the baby born in 1978 from an embryo frozen in the Mukhopadhyay’s home fridge, came forward before the press. In the years between 1978, when Dr Mukhopadhyay committed suicide and 2002 when Dr TC Anand Kumar acknowledged his pioneering work, the only memorial to the doctor’s memory was this film.

The uncomplicatedly-good doctor hero is a figure we see from the 1940s to 1960s, in the films Dr Kotnis kii Amar Kahani where V Shantaram played the role of a real-life doctor who went to serve in World War II, and Dil Ek Mandir where a surgeon played by Rajinder Kumar saves his former girlfriend’s husband. In both, the doctor dies, but this is a heroic death rather than the suicide of Dr Mukherjee. Incidentally, even in these years, there was the film Khamoshi where a dominating psychiatrist persuades the nurse played by Waheeda Rahman to look after two heartbroken patients. She refuses the second time, because she fell in love with the first patient. But the psychiatrist insists, and the nurse finds herself spiraling into a nervous breakdown.

Arguably, Khamoshi gets at the heart of a problem many people have with doctors— that doctors don’t listen to what people say. This is natural, perhaps, given the asymmetry inherent to the doctor-patient relationship, and equally, the doctor’s relationship with the nurse and others in the healthcare hierarchy. Doctors stand at the top of the order, they are the finest exam-crackers in a country of impossible exams, who can make them listen if they aren’t self-aware?

In a sense, Amitabh Bachchan’s career encapsulates the arc of the Hindi film doctor—from the disillusioned Dr Bhaskor Banerjee in Anand to the guilt-ridden Dr Jekyll to Mr Hyde in Bemisal to the Bhaskor Banerjee in Piku who only trusts a homeopath to understand the problems of the body. It’s interesting that Hindi film has read the relationship between doctors and society so astutely. It agrees with my own experience of the tone-deafness of doctors and the healthcare system as a reporter.

In my long months undercover at a maternity ward in government hospital, I saw medical students bark at birthing mothers, even when there were only two deliveries underway inside the labour room. They snapped at the families of patients: “All of you are called Najma bibi. Which Najma bibi?” The same residents would be polite with me, probably because I speak English, wear clean clothes, my underarms don’t smell.

In my years reporting on HIV-positive networks, I have seen activists brainstorm about how best to approach doctors about drug shortages so that they don’t lose their temper. When I interviewed doctors in ART clinics about drug shortages, they have complained that HIV patients write too many emails. Organ transplant doctors, who have years of specialist education, have advised me that women are generous by nature and I should not sensationalise figures showing that the majority of living organ donors are women. I have chatted with forensic medicine doctors through entire afternoons while their mortuary assistants, belonging to the caste of Doms, have conducted post-mortems in the morgue. At some point, the doctor would go in and sign the report, a matter of 10-15 minutes at most.

I remember how doctors over the years have responded to the work of Prof Sujoy Guha, who has spent four decades waiting for the approval for his original drug molecule called Risug, a male contraceptive. Several have called him a simpleton, an engineer pretending to be a medicine man (he is an IIT + AIIMs man). What gives them the confidence to dismiss the life’s work of a man whose clinical trials have always borne out his hypothesis, who has sustained funding for his work for nearly 40 years? Could it be the triumph of being the 0.1% who cracked an exam?

We are probably too awed by doctors as a society, too dependent on them in our individual crises, to perceive them as they are—products of a flawed, monstrous system. The media has failed at this too, possibly because our work requires repeat access to doctors and medical authorities. Strange as it may sound, it was cinema and Hindi film in particular, that gave me the perspective to report what I have reported. Or perhaps, it is not so strange after all—the camera gives distance, perspective and a certain freedom.

Every single one of us knows outstanding doctors, the sort that make us feel that if we’d met them earlier, we’d have lived better lives. I do, too.

A version of this essay was published in The Hindu magazine, 23 June 2019