The gift of an Amrita Pritam book in Soni feels like a little revolution. So does the library scene in Manikarnika

There is a moment in Manikarnika that nothing had prepared me for. The film is a biopic on the well-known historical figure Rani Laxmibai, a heroine of our high-school history. The trailer underlined the notes of this familiar story, of an unusually confident and martial 19th century queen who set out to avenge her husband’s humiliation by the British. The king of Jhansi (played by Jisshu Sengupta) seduces her with a book. He takes her to his library, pulls down a volume and she gasps. “I’ve wanted to read this book for a long time,” she tells him, and it is evident from the purr in her voice that she is seduced.

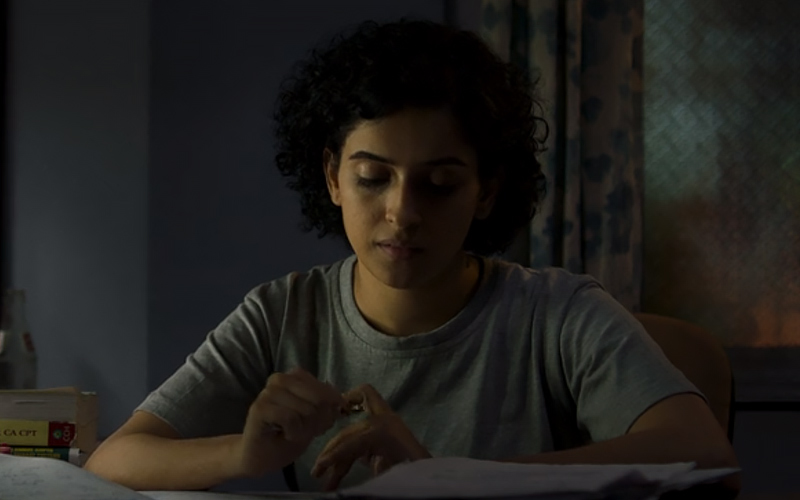

One week before Manikarnika opened, Netflix India released the independent film Soni, the story of two women police officers negotiating the savage misogyny of Delhi. Towards the end of the film, the senior officer, wealthier, better educated and more worldly, hands her younger angrier subordinate the memoir of the Punjabi writerAmrita Pritam, Rasidi Ticket. The title of the book is a story in itself: a male writer had once told Pritam that her own story would not fill a book, it could be something that could be written on the back of a rasidi ticket (revenue stamp), the older woman tells her younger colleague. The closing sequence of the film shows the younger woman in her new posting, the Delhi Police’s call helpline, a punishment posting for her. Seated at her work station, she opens the book to read, until a call comes through.

What experiences can a woman have that are worth writing about, Pritam’s male friend had told her. In Soni, one woman tells her colleague that Pritam’s memories may be the raft that helps her make sense of unreasonable, unseasonable things. “You might find some of your answers here,” Kalpana, the boss, tells her hot-headed colleague, Soni. The idea that reading can help us make sense of our lives is something that all of us readers hold as our life-jackets, but it feels revolutionary in a Hindi film, even more so because the author in question is a woman.

Women rarely read in a Hindi film—they cook, nurture, love, and more recently, enjoy sex, work in espionage and play (professional) sport. I don’t mean books as props, in the way that we spot a book (upside down) on Kajol in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, or Preity Zinta in a song in Dil Chahta Hai, or most memorably Sharmila Tagore at the train window in Aradhana. Here, the book is an accessory for flirting. I mean a woman who reads for pleasure or in solitude, where reading is a part of her identity to say that she can think, reflect, maintain an inner life.

2019 has been unusual in that respect. Also in January, there was Photograph, a romance between a affluent, class-topping chartered accountancy student, Miloni, and a ‘thirty rupees a print’ Polaroid camera photographer, Rafi, living on the margins of the city. Miloni is often in study mode, surrounded by thick volumes of accountancy textbooks. But she is clearly disinterested in accountancy, she turns away when she sees her topper photograph in hoardings in town. She was a talented actress who won awards in theatre and gave it up to concentrate on her studies, her mother says to an NRI suitor. But Miloni doesn’t let her overbearing family take over her life. She spends time wandering the city by herself, and when the chance to enter a make-believe love story presents herself, she enters whole-heartedly. What Photograph shows most unusually is a woman capable of imagination, and comfortable with solitude, a woman who spends a lot of time thinking. Though she is never shown reading anything, you know she is a reader, and a writer, at the very least of her own story.

Mission Mangal, the story of a mostly female team that steered India’s satellite to Mars, was a massive success at the box office. Vidya Balan is superb at selling the conceit that the premise to fry puris can also send a satellite into Mars’ orbit. But, the film’s emphasis on home science also diminishes it. The women are constantly bustling around running errands in the film, as if the director scolded them to make themselves useful. Only in one scene do we see Balan sitting on the floor and scribbling in a notebook—it’s a lovely little detail and the film would have been so much richer for more of this. Nevertheless, this is the first mainstream Hindi film where we see women creating outside the functions of reproduction. A lot more of this will hopefully be on screen in Balan’s biopic of Shakuntala Devi, the “human calculator” who is India’s first recognised female genius.

Think about it. If there have been artists, writers and creative folks in Hindi film, how many of them have been male? Akshaye Khanna in Dil Chahta Hai, Amitabh Bachchan in Silsila and Kabhie Kabhie, Guru Dutt in Pyaasa and Kaagaz ke Phool, Ranbir Kapoor as a photographer and singer through his filmography, it is all men isn’t it? To that end, the past decade is a start. The woman as reader, sometimes even writer and a creative, has made an appearance.

Consider Kalki Koechlin in DevD (2019), who is often found with a book in her face. When the life she knows derails due to a school sex scandal, she finds purpose in studying, giving exams, doing well. DevD came out in 2009, as a new decade was about to begin, and it is possibly the first time that a woman who is the romantic lead in a Hindi film is allowed to be cerebral. Even more interesting is Shor in the City (2011) where Radhika Apte is the literate young wife of an unlettered book pirate played by Tusshar Kapoor. She has read the books he sells for a living, and somehow the fact of this makes him lust for her and the written word.

In Lootera (2013), Sonakshi Sinha was perhaps the first mainstream Hindi film heroine who calls herself a writer. She teaches the hero how to paint, seduces him and later, when she is heartbroken by his betrayal, she struggles to put pen to paper. In the second half of the film, as dark circles grow under her eyes, I think her anger is as much against the words that don’t come as it is against the lover who abandoned her.

Aishwarya Rai is a poet in Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016), who says that she is not a successful writer. When she walks away from a relationship which is not reciprocal, I realised her writerly identity is not merely ornamental. Her realisation about the asymmetry in her relationship came from the same place of self-awareness which acknowledged her limited success as a writer.

In Phillauri (2017), Anushka Sharma plays the ghost of a 20th century female poet who wrote under a pseudonym because no one would believe a woman could write. She kills herself when her lover does not show up for their wedding. It’s not the shame of being stood up at the mandap, I think, because she is unembarrassed about her pre-marital pregnancy. It’s the fear that her lover had appropriated the credit for her poetry. The keenest reader of all, perhaps, is Ratna Pathak Shah’s erotica aficionado in Lipstick Under my Burkha. She reads all the time, before bedtime, minding the kids at the swimming pool, in the midst of engagement celebrations. Even when disaster has struck and she is shamed for her ‘dirty’collection, she wants to know how the erotic novel she was reading ends. How many readers entrust this much of themselves to the imagination?

Incidentally, the consequences of most of this reading -writing activity is unhappy—Sharma kills herself in Phillauri, Pathak Shah is publicly humiliated in Lipstick under My Burkha, Sinha is depressed to the point of nearly dying in Lootera. But I like what these films say about the women—that they are un-intimidated by men, unembarrassed about desire and sex, women who are trying out things for themselves.

I grew up watching several women like this in Bengali film, women who unsettled the grooves of their comfortable lives. Ray’s Charulata grows disillusioned with her marriage when she starts writing and getting published. The film is based on Rabindranath Tagore’s novella Nashto Neerh (The Broken Nest). And in fact, Tagore’s heroine’s appear repeatedly on the threshold of the home and the world, perhaps understandable given that he was writing at the turn of the twentieth century when women in colonial Bengal were at the centre of the ‘reform’ impulse of the National Movement. Ray, being shaped and taught by Tagore, featured the educated Bhadramahila figure repeatedly in his films (but strangely not in his own writing). In three Ray films, Aranyer Din Ratri, Nayak and Seemabaddha, Sharmila Tagore plays the same character—a person who uses her reading and sharp questions as a shield around romantic developments. In Ray’s Ghare Baire, the heroine Bimala gets drawn to nationalism and a firebrand nationalist friend of her husband’s, unsettling her own equilibrium. In Rituparno Ghosh’s Chokher Bali, the cerebral widow Binodini sleeps with her close friend’s husband, losing her friend and her abode.

‘Adbhut meye’ (What a strange woman), I can hear a voice in my head. It could be my grandmother, my mother, or even me. Why would these women behave like this? I didn’t understand them when I watched them growing up, perhaps I disliked them too. Now in my thirties, as I unmoor myself from some stable certainties, I am grateful for these women and the choices they made. Like them, I too read and spend a lot of time by myself, ‘overthinking’ things, making choices that find no ready resonance. It’s comforting then to think that some women I know are like this too, choosing their own solitude over the security of practical things.

This essay was first published on Film Companion

6 comments for “Why A Woman Who Reads is Still Unusual in Hindi Film”