The Bengali films Tasher Ghawr and

The Lovely Mrs Mukherjee show the domestic servitude written into subcontinental marriages

Some days after Prime Minister Narendra Modi locked us down on 25 March with the battle analogy of the 18-day Kurukshetra war, the celebrity housework videos began. Then, the men who did not have cameras installed for easy recording provided dishwashing updates, and gradually, washing shortcuts and tips, on Whatsapp chats. By the middle of April, three weeks into one of the longest and most draconian lockdowns in the world, the feature stories in newspapers about men participating in housework began.

What was barely seen (even on social media), were the stories of “housewives”, those for whom housework did not feel like an adventure to showcase. Women who may have had access to social media, but the lockdown eroded their free time savagely. There was a certain kind of privileging of cooking on social media, but these were not the women who were exhausted with cooking and cleaning and meal-prepping and childcare and eldercare. (The women who shared their lockdown days on social media were women something like me—working women with a social media savviness, not to mention other kinds of privilege.

Domestic labour, or unpaid servitude, is rarely documented outside recent academic work. In the newsrooms I have worked in, editors take the domestic labour of women as the given. What is the story here is the counter-question, they’d ask. The Nobel-prize winning writer Alice Munro has mentioned how one of her first newspaper profiles was headlined, “Housewife FInds Time to Write Short Stories”. What did a day in the life of a “housewife”, an unfortunately laden term in Anglophone discourse, look like in the lockdown? How much solitude had gone, how many pleasures remained, what things were gained? What do they tell themselves if they are hit? Do they get enough sleep at night?

This is the story that the 46-minute Bengali film Tasher Ghawr (A house of cards) tells. What is it like to be a housewife forced to be at home with a husband she has disliked for a long time, a man who is having an affair, beats her sometimes and rapes daily? Perhaps it is mutual dislike. But we only see and hear the point of view of Sujata, played by Swastika Mukherjee. The film is a solo act by Mukherjee, she is the only person you see and hear on screen. The husband’s face is never shown though his voice is heard, ordering her to serve food. There is a mother-in-law who appears for a moment on screen but has no spoken lines.

The story is set in the hours from breakfast to lunch of one locked-down day, but goes back and forth months and years fluidly as Sujata recounts her marriage, her miscarriages, the solitude she relishes as her husband embarked on his affair, the smell of the blood that spills when she is beaten up and the its difference from the blood that flowed when she miscarried. Throughout these memories, we see her dusting cushions, tidying up the flat, prepping food, baking cakes to poison the rats, carefully raising the whistle of the pressure cooker to let out steam.

The film uses the device of Sujata speaking to us, the viewers, directly but you get the sense that she is conversing with herself, arranging her thoughts, processing her feelings. This is what she probably does on normal days, but the lockdown has savaged her oases of quiet because her husband is always demanding something to eat. She starts prepping lunch even before breakfast is over. She sips a cup of tea while serving her husband breakfast, but doesn’t eat herself.

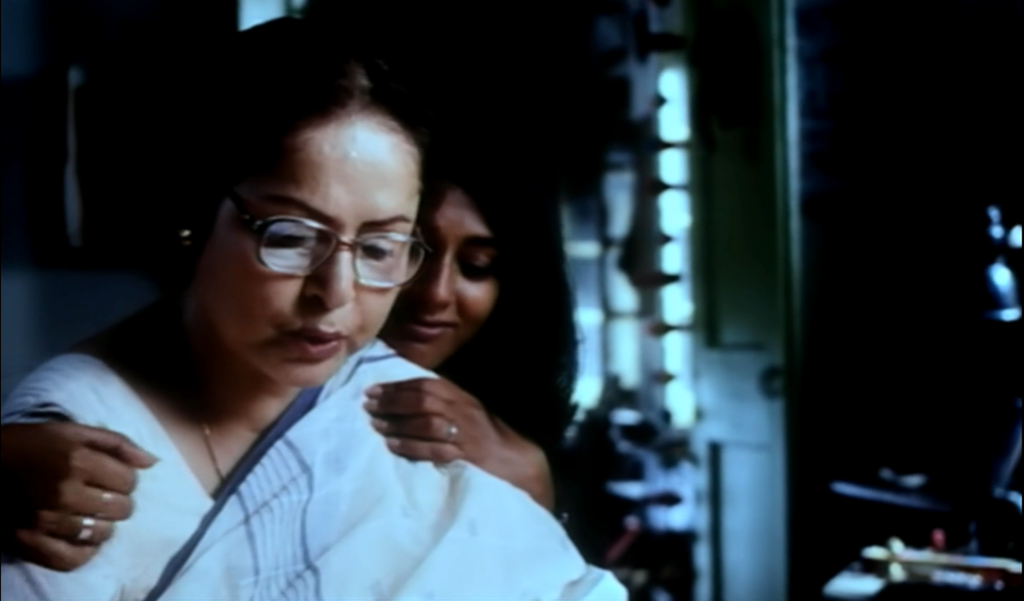

The companion piece to this film is The Lovely Mrs Mookherjee, a 50-minute film that released last year on Zee5, starring Bratya Basu and Swastika Mukherjee (again) in the lead. The tone is different–this is a sharp, laugh-out-loud comedy as against the ruminative (but never glum) nature of Tasher Ghawr. Here, Mukherjee is a Rabindrasangeet tutor, Minu, who becomes a “housewife” for a Rs 5 lakh dowry to enable her brother to get a job in the lower ranks of the police. Her husband has had indigestion for six months, and needs someone to cook his meals as lovingly as his mother did. Minu’s arrival gift as a bride entering her husband’s home is a handwritten book on her conjugal bed, titled ‘Non-vegetarian and Vegetarian Dishes’ by her late mother-in-law.

Here again is the motif of making and serving food, and much else. Minu, a self-employed woman who previously provided for her father’s family, now spends her days cooking from her mother-in-law’s recipe book, dusting, ironing her husband’s clothes. The one time she sits down for riyaaz, her husband informs her that her singing is distracting him from writing his Nobel-winning verse novel and asks her to practise in the afternoons when he is at university.

In fact, Mukherjee essays a housewife with an anxiety condition in her brief, luminous performance in the Hindi web series Paatal Lok as well. Dolly Mehra hasn’t had children, she thinks her beauty is gone, she knows her husband is having an affair. Perhaps she doesn’t have to perform the physical labour of cooking like Sujata or Minu, because she enjoys the affluence of Delhi’s powerful media economy, but she serves a similar function in star journalist Sanjeev Mehra’s life I think. She keeps his home beautiful and welcoming, she is a service-provider, more Mrs Mehra than Dolly. There is another housewife in Paatal Lok, in fact, Gul Panag plays Renu Chaudhary, protagonist Hathi Ram Chaudhay’s wife. We see her managing the tensions between him and his teenaged son, and her brother but the show does not dwell on what her days look like.

Consider a film like Hum Aapke Hain Kaun! for instance, which spends some screen time on the daily life of “housewives”. The work of cooking, prepping for ritual ceremonies, waiting to feed the men returning from work is shown here, but these are shown from the outside, without detailing the work involved. Staying up to feed hero Prem (Salman Khan) when he returns really late is framed as a romantic song (Pehla Pehla Pyaar Hai). To be clear, there is absolutely nothing wrong or embarrassing about domestic work. But this manner of depiction glosses over the work involved.

This continues 25 years later with a film like Mission Mangal, which is about a team of rocket scientists. Think about how Tara Shinde (Vidya Balan) is characterised: she is often shown cooking and rushing with household work. One of the film’s conceits is that frying puris gives her a vital idea in the design for the satellite that India sends into Mars’ orbit. Unlike Hum Aapke Hain Kaun, the labour of domestic work is not glossed over, but it is certainly privileged–Tara Shinde’s team is full of home science ideas. The fact that Shinde has to manage the household as extensively as she does, given that she holds a power job, and her husband does not chip in is not questioned. This is the kind of portrayal that perpetuates the socialisation of girls into house work. ‘If space scientists can manage both home and work, why not you?’ is the sentiment I imagine .

Balan’s Tumhari Sulu, came close to exploring the cost and consequences of being labelled as the official person to do housework in an Indian household. Sulu, played by Balan, wants to pursue her dreams of becoming an RJ and gets there as well. Her partner is encouraging till it starts disturbing the convenience of Sulu doing all the housework herself. However, the drudgery of Sulu’s housework begins to seem unfair only in comparison to the excitement of having a big dream. The film concludes with a similar messaging as Mission Mangal, showing Sulu straddling both with aplomb, in fact, turning her cooking skills into a tiffin business her husband runs.

A certain kind of ‘posh’ Hindi film does not dwell on domestic work at all. It invisibilises that labour, whether of women or of domestic help completely. This is the aesthetic of Dharma Productions, Yash Raj and filmmakers who have invoked that aesthetic of wealth.

This year there were two Hindi films that did consider the gender skew in domestic work. Panga is about a kabaddi player, Jaya Nigam (Kangana Ranaut) who returns to play for the national team after several years devoted to bringing up her son and looking after home. The film takes an affectionate but effective look at just how much work Jaya did at home–cooking, looking after her son, keeping her husband well-fed and clothed–although both husband and wife work jobs. But like Mission Mangal, it is too sweet-natured about it. The misshapen rotis made by the husband, a loving Hindi film stereotype about men in the kitchen, is once again an endearing thing. My concern is that this makes the inequality seem inadvertent, not really something that one gender actively benefits from.

Thappad takes a more critical approach–it details Amrita Sabharwal (Tappse Pannu’s) long day which begins hours before her husband’s and ends much after his. My favourite sequence is when Pannu’s husband turns on her for looking after his mother, and calls it performative caregiving.

Both these films are important for looking at how gendered housework is. What I like about Bengali film is that it does not try to make this skew adorable with sweet kitchen sequences, and it endows the women trapped in such servitude with more awareness and agency.

Bengali films bring out the domestic servitude in marriage more frankly than Hindi cinema does. (I consider Paatal Lok to be in the category as an indie Hindi film–its production aesthetic is a continent apart from Ekta Kapoor’s K-serials, that were set in domesticity.) The details of Sujata and Minu’s day, for instance—sprinkling water before ironing a kurta, serving snacks to husband and his drinking buddies, hanging up clothes to dry on the terrace—it brings out the unequal exchange that is at the heart of most marriages. Data puts precise numbers to this inequality: women in urban India spent 312 minutes a day on unpaid care work, men 29 minutes, according to 2019 ILO report.

This awareness is primarily the legacy of writer-director Rituparno Ghosh. The promotional material of Tasher Ghawr referenced Ghosh, in fact. Most of his work is alive to who keeps households running and fed, women, housewives and domestic help. But I want to end with Shubho Mahurat, Ghosh’s take on the Agatha Christie novel, The Mirror Crack’d From Side to Side. In this film, the Miss Marple is an elderly widow Ranga Pishi, played by a marvellous Rakhi Gulzar. She has no children of her own, her life is entirely centred on domesticity and TV serials, she has never held a job. She solves a murder by a major film star, one whom she is a fangirls herself, without stepping out of her home. When her visiting niece (Nandita Das) acts up with her, she asks her to leave. “Don’t think I have an empty life. I have my TV and cats and books and magazines. I don’t need more. ”

Ghosh dedicated the film to all the Miss Marples who let their sons skip school when they complained of stomach ache, despite knowing the truth. Like Sujata and Minu, Ranga Pishi had turned her cage into a garden of solitary pleasures.

This essay was originally published in Huffington Post, India.

3 comments for “The Unpaid Labour of Housewives”