Chatterjee worked closely with late Oscar-winning director Satyajit Ray, one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Worked his entire life in the Bengali film industry, eschewing the more lucrative Bollywood

Noted Hollywood director Martin Scorsese once said the four most influential auteurs of the 20th century were India’s Satyajit Ray, Japan’s Akira Kurosawa, Italy’s Frederico Fellini and Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. With the death of star actor Soumitra Chatterjee of complications from Covid-19 in Kolkata on Sunday, the last living association to that classic age of the art film is gone.

The 85-year-old Chatterjee, one of Indian cinema’s most famous faces, collaborated closely with Ray, whose critically-acclaimed films won multiple awards including the Oscar for lifetime achievement, putting India on the global cinema map. In fact, all four late directors were Oscars winners and together have influenced other acclaimed filmmakers including Scorsese, George Lucas, Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu and Wes Anderson.

The directors Ray, Kurosawa, Fellini and Bergman were all influenced by the neo-realist style of filmmaking – which eschewed big stars and used simple non-lavish locations – and worked without the support of large, affluent studio systems. The impact of their work on later filmmakers closed the gap between art and mainstream films, paving the way for the abundance of content available on streaming platforms today, spanning languages, budgets and filmmaking styles.

Chatterjee acted in 14 of Ray’s 30 full-length feature films – however the online film and movie database IMDb lists him as having no fewer than 306 acting credits over a 61-year career. He typically played upright characters with a palpable vulnerability and is among a select niche of actors whom audiences saw ageing in real time on screen, akin to Robert de Niro and Jack Nicholson in Hollywood.

His performance as the taxi driver Nar Singh in Ray’s Abhijan (1962) is said to be one of the influences for the character of Travis Bickle, played by De Niro, in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. He is considered to be in a hallowed league of select performers comprising Toshiro Mifune, Marcello Mastroianni and Max van Sydow. Van Sydow died in March this year; he had acted in 11 of Bergman’s 53 full-length feature films. Mifune worked in 16 of Kurosawa’s 31 feature films, and Mastrioanni was in four of Fellini’s 19 films. Both actors died in the 1990s.

Chatterjee worked throughout in Bengali film, never feeling the urge to cross over to the more lucrative and popular Hindi film industry popularly known as Bollywood, unlike his contemporaries Uttam Kumar, considered to be the all-time superstar of Bengali film, and his frequent co-star Sharmila Tagore.

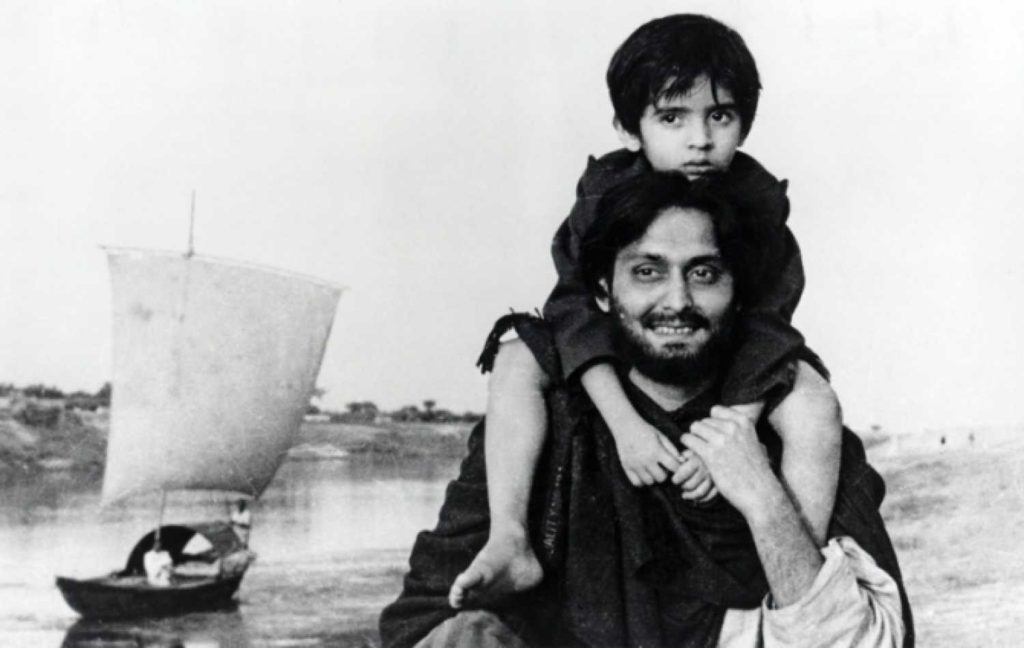

He made his debut in the 1959 film Apur Sansar (The World of Apu), the third in Ray’s internationally recognised Apu Trilogy. Chatterjee played a young man who saves a teenage bride from ignominy on her wedding night when her groom fails to show up. It is an unusual story, especially for foreign audiences for whom the idea of an arranged marriage would have been odd. Yet the film picked up prizes at the London and Edinburgh film festivals, and is listed among the top 100 all-time greatest films in Sight and Sound, the prestigious magazine of the British film institute, and Village Voice, the celebrated New York magazine.

In his second film Kshudito Pashan (The Hungry Stones), based on a story by Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, Chatterjee was cast as a young government servant who falls in love with a ghost. It is a gossamer make-believe conceit that works on plausibility, but Chatterjee’s earnest supple face made it completely believable.

He typically played characters who spend a lot of time thinking. This is not to say that he only played intellectuals or characters who brood, but rather that he had the gift of making the audience see him reflecting on his thoughts. This is not an easy thing to perform – thought is the opposite of action; it means doing nothing. But his was the sort of lucent face on which one could see a shadow fall.

Other films Chatterjee made with Ray that won global recognition include Charulata (The Lonely Wife), Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest), Ghare Baire (The Home and the World) and Ganashatru (Enemy of the People).

In 2012, Chatterjee received the Dadasaheb Phalke award, the award for lifetime achievement in cinema given out by the Indian government. In 1999, the French government awarded him the Commandeur de l’ Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, the highest award it gives to artists.

When he won the Indian government prize, he singled out one film for mention in a career studded with classics. He highlighted Koni, a 1984 movie directed by the relatively obscure director Saroj Dey about a girl living in the slums of Kolkata who triumphs over hardships with the help of her swimming instructor, played by Chatterjee.

He said: “According to me, it was one of the best films I worked in. The film had such inspirational value. The film’s catchline ‘Fight Koni fight’ became a mantra for success for every struggling middle-class Bengali at that time.”

Before embarking on his film career, Chatterjee worked as an announcer at All India Radio in Kolkata. He was also an accomplished playwright and a poet.

Right until the end, he was an outspoken political activist, identifying as a leftist. One of his last major acts of dissent was signing a petition against Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi government’s polarising Citizenship Amendment Act, which offers Indian citizenship to persecuted refugees of all religions in South Asia except Muslims.

Chatterjee’s daughter, Poulami Bose, said her father died in hospital after having been admitted in early October, when he tested positive for the coronavirus. He is also survived by his wife and a son.

This obituary was originally published in the South China Morning Post