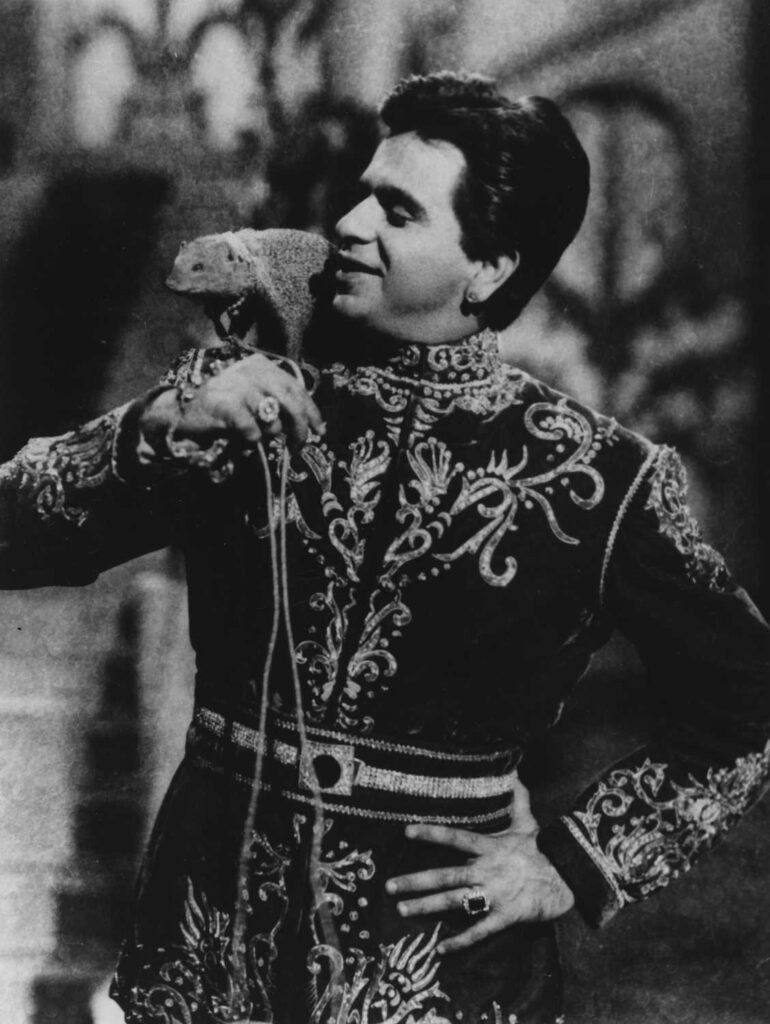

So much has been written about Dilip Kumar, the legendary actor of Hindi cinema. Less has been said about Kumar, the citizen. He was the man we wish our superstars were today: peerless in his craft, committed in his convictions

When Dilip Kumar died in July 2021, a four-year-old blog post on roundtableindia headlined ‘A Baghbaan of the Pasmanda Movement’ started circulating on Twitter. Its contents were frankly astonishing, more so because it was so little known. It recounted how Kumar became a part of an awareness campaign to encourage backward-class or Pasmanda Muslims to take advantage of the OBC reservations that were recommended by the Mandal Commission report. This was 1990, and Kumar had been considered a living legend for at least a quarter-century by then. The post detailed, with a handful of photographs as well, how Kumar personally attended close to 100 meetings in smaller cities and towns across India to address the problem of caste among Muslims for the organisation All India Muslim OBC (AIMOBC).

It is a popular belief that caste does not exist among Muslims, indeed many Hindus today deny caste as well. But more than anything else, the thought that a living legend—several orbits over superstardom—had worked quietly on the ground for a social cause was stunning. How often have we complained that Bollywood stars do not comment on politics? When BlackLivesMatter was used by filmmaker Karan Johar and actors Sonam Kapoor Ahuja and Priyanka Chopra in the summer of 2020, the summer of the horrific migrant crisis of the pandemic, they were promptly, and rightly, called out for their silence on politics at home. How often have we realised that donations and campaigns by stars are publicity stunts? How often have we asked, why can’t Bollywood stars be political like they are in Hollywood?

Like many viewers of Hindi cinema, I have been in awe of Dilip Kumar the performer for years. I hadn’t realised how moved I would be by Dilip Kumar, the citizen, the man of conscience. I had known that Kumar was a public-minded man, that he was appointed Sheriff of Mumbai—a respected but decorative post with no powers. After his death, I would repeatedly watch an interview he gave NDTV in 2000, in which he calmly said it was “abominable” that Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray had asked that he return Pakistan’s highest honour, the Nishan-e-Imtiaz, or go back to Pakistan. “These are the fascist ways of fascist administrations. It’s not a good sign,” he said, spacing out his words, without a trace of anger or outrage. Whether one agrees with his political view or not, it is hard not to admire that kind of clear articulation. But work that takes you to 100 public meetings, about which little was known in the public until a couple of years before he died—that is a commitment, isn’t it?

Think about it. Kumar is known for his delicate and superb Urdu pronunciation. For his sophistication, his soft-spokenness, his erudition, his interest in poetry, that you know he came from an affluent, educated background. He was an elite aristocratic upper-caste Muslim, unlike the Pasmandas for whom he travelled across 100 cities and towns in India. Indeed, so refined that even the First Lady of Indian cinema, Devika Rani, was impressed.

By now, the story that Devika Rani Chaudhuri, actor, producer, the first winner of the Dadasaheb Phalke award and the boss of Bombay Talkies, discovered him and gave him his screen name is well-known. But in fact, Yusuf Khan came recommended to Devika Rani by her husband Himanshu Rai’s psychiatrist Dr ‘Cracky’ Masani, wrote Kishwar Desai in her book The Longest Kiss. “He (Yusuf Khan) is a very keen and intelligent young man and has always wanted to be a film artist. From my knowledge of Mr Yusuf Khan, his desire is a sincere and earnest one, and I shall be grateful if you will help him in any way you can,” wrote Masani in a neat scrawl (Desai’s book reproduces the note).

In his autobiography The Substance and the Shadow, Kumar wrote that he was embarrassed to discover that his salary was Rs 1,250 a month while his contemporary Raj Kapoor, a childhood friend from Peshawar and a close friend in the Bombay industry, was paid only Rs 170 a month in Bombay Talkies.

Devika then forwarded the note to a colleague with an annotation above: Dr Masani has sent this young man and by his letter that he wishes that the boy gets something. He comes from a respectable (family). Devika’s insistence on ‘respectability’ was the cause of disagreements with her husband Rai. She herself always emphasised her connection to the Tagore family of Calcutta and her training and exposure to Europe.

Certainly, the young man made a considerable impression on her. Not only did her studio Bombay Talkies launch him as Dilip Kumar in Jwar Bhata (1944), but also paid him a substantive salary by their own standards. In his autobiography The Substance and the Shadow, Kumar wrote that he was embarrassed to discover that his salary was Rs 1,250 a month while his contemporary Raj Kapoor, a childhood friend from Peshawar and a close friend in the Bombay industry, was paid only Rs 170 a month in Bombay Talkies.

Clearly, Devika saw something special in him. (She is known also to have introduced Madhubala as Baby Mumtaz Jaan in Badal, 1940, and Kumudlal Ganguly as Ashok Kumar in Jeevan Naiyya, 1936). With due apologies to the legacies of Raj Kapoor and Dev Anand, it is hard to disagree with Devika’s judgement today. Unlike his iconic contemporaries who are known for their mannerisms—Raj Kapoor’s Chaplinesque persona and Dev Anand’s delightful neck mudras—Kumar is shorn of any such distinctive mannerism. He is sometimes compared with Aamir Khan, sometimes called the most serious actor of the triumvirate of Khans, but in fact even Aamir has a distinctive careful style of dialogue delivery. Kumar had no such characteristic in his performances.

So many superlatives have been used for his work and by such notables that it can feel intimidating to approach a Dilip Kumar film for someone new to his work. (Two of these notables are Amitabh Bachchan and Naseeruddin Shah, often called Dilip Kumar’s closest contemporaries in terms of acting talent in the Hindi film industry. “When you see a particular scene enacted by Dilip sahab, you are convinced that there can never be an alternative to it,” Amitabh Bachchan said about him. “When we did the film Karma together, the publicity machine made it out into a duel. It was a one-sided duel, and I knew I was not in the same orbit as Dilip sahab… I was terribly nervous about it, that’s the only time I was nervous while acting in my life,” Naseeruddin Shah said in an interview.)

Is it possible to watch an actor so revered and be honest? What if it feels melodramatic to watch him? Or dated? When I first watched a Dilip Kumar film in college, as part of a film studies screening, my apprehensions were extinguished. Here is an actor who is so minimalist, so relaxed that he can make even the greatest of Hindi film naturals, Nawazuddin Siddiqui, feel slightly excessive. Perhaps the idea that Dilip Kumar may be dated comes from the near-continuous circulation of the songs and reputation of K. Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam, 1960. But then, this is a film set in the 16th century and Kumar’s body language, and indeed, the entire cast’s, would be heavier, exaggerated—modelled along the postures seen in paintings of the era. Or perhaps because of the moniker Tragedy King bestowed on him. Try Kohinoor, 1960, another period piece but a joyous, fleet-footed romantic comedy starring, as it happens, Tragedy Queen Meena Kumari. Or watch the atmospheric, Madhumati, 1958, the best ghost story written in Hindi cinema which was the inspiration for the twist half a century later in Om Shanti Om, 2007.

To watch Dilip Kumar on screen outside of Mughal-e-Azam is to see an actor who always under-acts, who does so little that you sometimes bend forward to watch and hear him. Like it were a person in front of us, not a camera and a set. It’s as if he were never anxious that a performance was inadequate. Like the clear prose of the English-language novelist J.M. Coetzee or the Bengali writer Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay, where not one word is in excess, not one gesture would be out of place. But this does not mean he was stone-faced or stoic. Rather, it was the kind of lucent face on which you could see a shadow fall, and equally, the light dazzle. The minimalist with a dazzling smile.

My book The Day I Became a Runner offers an alternative history of the republic, from the late 1930s to the present moment, through the lives of 9 women athletes. It is available on Amazon and bookstores across India.