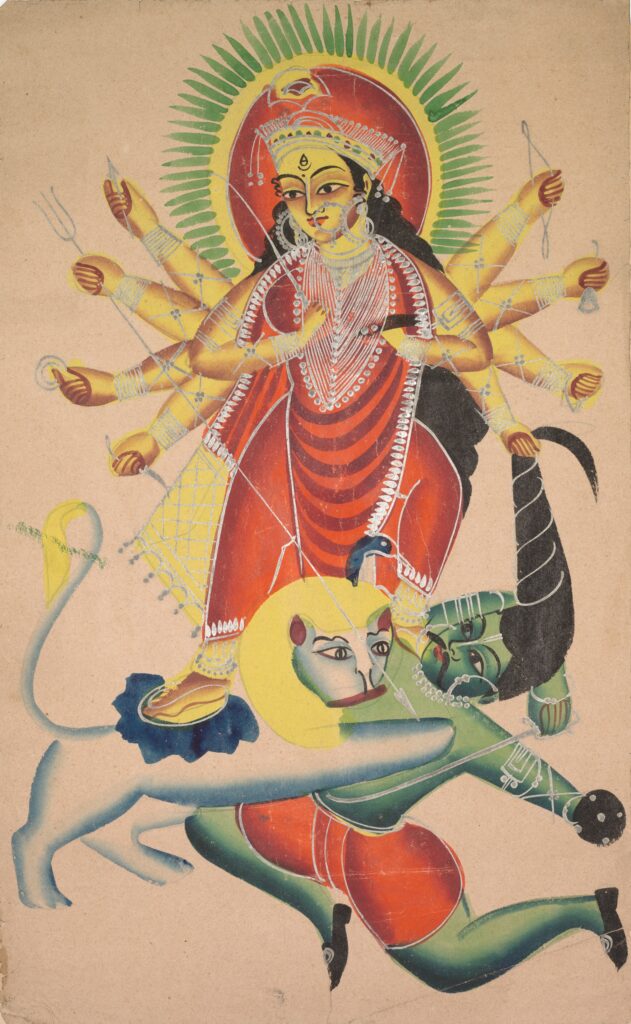

In our two epics, Ram, Lakshman, Arjun are star warriors, but battles are not won on their skill alone. Divine intervention and deception are needed. The story of Durga’s 10-day marathon battle that cemented her place among the top of the gods underlines her strength, willpower and stamina—all the things that count in sport

The story about physical exercise that I hear most often growing up, is the story of the gods Ganesh and Karthick. Their parents Shiva and Durga set them a task of go around the world thrice. Whoever did ths first would win a celestial mango, gifted by Brahma. Karthick, the younger, a handsome serious-looking god, mounted his peacock on Mount Kailash and flew around the earth three times. His elder brother Ganesh, the genial looking, slightly overweight elephant trunked god, walked around his seated parents three times and claimed the mango. Why, his parents asked. Because you, my parents, are my whole world, Ganesh told them.

Ganesh won the mango. I heard this story very often from my parents. They delighted in its clever ending. My father watched a lot of sport on television, essentially anything that moved, but this was the only mythological story I heard that had anything to do with physical exercise. This was the definitive tale, the evidence that we Indians do not have sport in my configuration. On sports day, my mother usually persuaded me to bunk school and use the day to study. Sport is for viewing, don’t waste time doing it. My parents, who generally disagree on most things, were largely in agreement on this. I remember it now especially as I work on this book.

Truly, are there no other stories?

I grew up with the televised spectacles of the two epics synonymous with Hinduism—the Ramayana and the Mahabharata—in my single-digit years. I remember furious sequences of action spanning multiple episodes which produced silence and deeply-furrowed brows among viewers. There was the war on Lanka in the Ramayana, the Kurukshetra war in the Mahabharata, and several episodes of duelling and confrontation among arguing princes and kings in both epics. The apocryphal story of the 1980s goes that on Sunday mornings 10 am, when the Ramayana and in subsequent years the Mahabharata were telecast, the roads were deserted, shop shutters downed, only the lurid sounds of the televised epics echoed in the outdoors.

When I say sport, I mean any activity that requires bodily exertion and is structured by some rules, some dos and don’ts, even if the activity is not directed towards a definitive win or loss. For instance, mace wielding or archery, may be practised for the pleasure it offers. But there must be some perspiration, some rationing of breath, some baiting yourself to go a bit further

Arrows aimed by opposing parties met with precision mid-air, the point of their convergence highlighted by graphic shapes of colour forming around them until they neutralised each other and dropped down. Lethal spinning cymbals would depart from launching hands to decapacitate limbs and heads or stop approaching chariots and return to their owners again. Racing chariots would often abandon their earthbound paths and head skywards in defiance of gravity. Sometimes, ambitious flying chariots would be met by well-aimed arrows or cymbals and brought back to the ground. Maces were swung in vast, fearsome arcs. All this was accompanied by singing, often choral, as if the elements were ringing out in support of the warriors in action.

When I say sport, I mean any activity that requires bodily exertion and is structured by some rules, some dos and don’ts, even if the activity is not directed towards a definitive win or loss. For instance, mace wielding or archery, may be practised for the pleasure it offers. But there must be some perspiration, some rationing of breath, some baiting yourself to go a bit further. When I revisit the battle sequences of the epics now, I find there is little record of excellence in battle sport as we may understand it, although we are told of superb archers and incredible mace fencers. Most of all, there is no evidence of their skill definitively winning the day.

I’ll explain. In the Ramayan, for instance, early in the battle with Ram, Ravan’s son Indrajit (Meghnad) shoots Rama and Lakshmana unconscious with well-aimed arrows. Indrajit is described as a supreme archer, and a terrific all-round martial expert. But soon after he strikes Ram and Lakshman, a mysterious eagle materialises who neutralises the arrows and enables Ram and Lakshman to arise. At another crucial point in the battle, the gods Brahma, Shiv and Indra send Indra’s chariot to Ram. This celestial gift is a flying machine that enables Rama to rise above the ground and take aim at enemy positions. It also repels all the arrows that the Ravan aims at him with all his 20 arms. Ram also possesses the divine weapon series called Brahmastra, known to have frightening consequences once deployed, which he uses a number of times in the Ramayan. In the final showdown with Ravan, this is what fells the king of Lanka. Besides, here’s the thing: Ram’s army is comprised entirely of monkeys commanded by Hanuman. In other words, the human labour of battle is nicely outsourced to the vanar sena (army of monkeys).

The battle between Ram and Ravan is evenly pitched until the gods tilt the balance decisively in Rama’s favour with strategic celestial gifts. Ravan and his son Indrajit (Meghnad) are described as outstanding warriors. And Ram—from his virtue alone, you know he possesses a deadly discipline that makes him a formidable opponent in battle. Yet, it is heavenly intervention that wins the day for Ram’s army.

We see this kind of thing in the battle of Kurukshetra in the Mahabharat too. There are three turning points, arguably, in the 18-day battle. The first is the felling of the general of the Kauravas, Bhishma, who uncle to the Kauravas and a terrific battle hand. In Kurukshetra, he looks invincible, and Krishna hits upon the idea of using the transgender identity person Shikhandi to defeat him. Bhishma had taken a vow of celibacy, which had earned him a boon from Brahma that no man would be able to kill him. When Shikhandi stood before him in the battleground, Bhishma refused to raise a hand on him, making it easy to fell him.

Second is Arjun’s face-off with King Jagadarth on day 14 of the battle. The previous day, Jagdarth had killed Arjun’s son Abhimanyu, who is known as the best and bravest of warriors. Jagadarth is the brother-in-law of the Kauravas, husband to their only sister. Devastated, Arjun swears to kill Jagadarth, and promises that if he fails to accomplish this by sundown of day fourteen, then he will kill himself instead. The entire Kaurav army rallies around Jagadarth to protect him, because they believe Arjun will keep his word. Facing down an entire army alone, when it looks increasingly unlikely that Arjun will able to avenge his son’s murder by sundown, Krishna causes an eclipse of the sun. As sunlight falls, the Kaurava army think it is sundown and drop their guard, exposing Jagdartha. The next moment, the sun comes out of eclipse and Arjun slays Jagadartha.

On day 15 of the Kurukshetra is the death of Dronacharya, a martial arts expert and the teacher of the Kauravs and the Pandavs. In the battle, he fought on the side of the Kauravs. As the guru of all the warriors on the field, Drona is naturally superb and frankly untouchable. It is Krishna, again, who suggests that the Pandavs weaken Drona by claiming that his son Aswatthama, also a formidable warrior, was killed. To do this, Bhim kills an elephant called Aswatthama and loudly proclaims Aswatthama is dead. Drona hears this and turns to Yuddhistir for confirmation because Yuddhistir never lied. He, the truthful, confirms the news by saying: “Aswatthama hata, iti (Aswatthama injured, and dead.)” Then he adds in a whisper, “Gaj (an elephant)” which Drona doesn’t hear. Grief-stricken, he retires from the battlefield. Thereafter, the big guns felled, the Pandavs win easily over the next three days.

Notice the similarities between the two epics. The warriors in both are marvellous, those from the losing side as well as the winning side. They are all renowned for their martial prowess. Arjun is the supreme warrior and especially talented at archery, Dronacharya is skilled in the use of special weapons (astra) in the Mahabharata. Ravan’s son Indrajit is a singular talent at archery, Ravan himself is a noted warrior in the Ramayan. Bhishma, the general of the Kauravas, is peerless in his battle skills, Arjun’s son Abhimanyu is valourous like few are. Individually, they are all highly accomplished.

Yet, the 10,000 hour rule that Malcolm Gladwell laid down as the minimum threshold for success doesn’t hold here. Duels and battles are won not by skill, but by divine intervention or deception. To be certain, each of these super-warriors has logged far more than 10,000 hours of practice in martial skills, but this in itself is not enough for victory. You must either have the gods on your side, or you must play dirty.

If every heroic character is individually excellent, but not outstanding enough to triumph on martial skill alone, then it is hard to make an argument for a sports hero. What this is, is the opposite of sport as fair play: it speaks of divine favouritism, and deception that is rewarded with victory instead of being punished.

Hinduism is said to have 33 crore gods, but the three principal divinities are Vishnu, Shiv and the goddess Shakti (whom we know in the form of Durga, Kali or Parvati). The Ramayan and the Mahabharat are the adventures of Vishnu on earth: both Rama and Krishna are avatars of Vishnu. These three reigning stars are also related to one another: Shiv is married to Shakti, and in many interpretations, Parvati and Vishnu are siblings. Parvati’s angry avatar Kali is dark-skinned as is Vishnu’s avatar Krishna. In other accounts, Visnu is married to Lakshmi and Saraswati, the daughters of Shiv and Shakti. The remaining 32,99,99,997 divinities are related to Shiv, Vishnu and Shakti in some way. As such, no one carries the mantle of god of sport. Are we a culture that doesn’t value sportsmanship?

Shiv is a promising persona to consider. He is renowned for being a beautiful dancer—108 of his mudras (dance positions) are described in the Natyashastra, the handbook of the ‘Sanskrit’ (read classical Hindu) performing arts. His dancing is said to be responsible for the destruction of the universe as well as its creation, this is known as the tandav. Yet, there is no sustained description of the dancing in the written sources. The Natyashastra provides the description of his dancing poses, there is almost no description of the stamina or velocity required for his universe-destroying and creating performances. How long did he dance? What effort did it cost him to break the universe, and set it up again? Did he ever fall out of breath or despair? How did the mountains and seas come into being, did he shape them with his mudras?

There’s only one little anecdote about Shiv’s dancing that comes up often: one time he was competing with Parvati in a competition, and she matched him step for step. The Nataraj, as Shiv’s dancing form is called, had met his equal. Each pose that he struck, she performed just as gracefully. And then, Nataraj’s earring fell off mid-dance. He picked up the trinket with foot and effortlessly lifted his leg to slip the earring back in his ear. Parvati was too shy to match steps on this one. And so, Shiv won. Once again, it feels like a gimmick. A showy, smart alec move that plays to the gallery. Very much like Ganesh walking around his parents, Shiv and Parvati, to beat his brother Karthick. Like father, like son.

The closest we have to a vigorous action hero is Shakti, the goddess. For more than nine days, she does battle with the buffalo demon alone, and finally defeats him. There is little in common between her and our women athletes except their sex. The goddess was prepped with great care by all the gods. For much of India’s history in international sport, our women have been given nothing except permission to participate. Like Mahishasur, no one expected them to perform, certainly not our infamous sports bureaucracy. But like the goddess who won so memorably that she secured her place among the top drawer of Hindu divinity, these women have extended their memo by far.

The goddess Shakti is different, there’s something there. The story of her creation and the terrific endeavour that cemented her place among the top of the gods underlines her strength, willpower and stamina—all the things that count in sport. The story goes that that the son of a demon and a beautiful buffalo called Mahishasur became a tremendous warrior with discipline and long hours of meditation (tapasya), and rose to became the king of the underworld (patal-lok). He then won over earth (dharti lok). His tapasya and merit earned him a boon from Brahma, that giver of problematic boons. Mahishasur won the immunity that no male form could kill him, he would meet his death only at the hands of a female force. The buffalo demon had laughed when he heard this, because there were no women among the panel of top-drawer gods. He was assured that he was as good as invincible with Brahma’s blessing.

Thus fortified, Mahishasur won over the realm of the gods (swarg lok) easily, and became the lord of all three worlds. This is when the gods came together, led by Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, to create a female force to defeat the buffalo demon king. This is Shakti. In her ten arms, she is armed with the weapons gifted to her by several gods. These are not throwaway weapons, the gods wanted her to win. With these, she takes on the buffalo demon Mahishasur. For nine days, the battle rages between Mahishasur’s army and Shakti. He is a shape-shifter and appears sometimes as a lion, sometimes as a handsome man and sometimes as a buffalo. He proposes marriage to her, and offers the three worlds as a perquisite of being his consort. Shakti is not distracted. On the tenth day, the goddess finally slays Mahishasur. The three worlds are restored to the gods. Shakti makes her place among the very top of Hinduism’s hierarchy.

She is focussed, undeterred by Mahishasur’s shapeshifting and proposals. She is skilful and strong, holding forth alone for more than nine days. She has the endurance of a seasoned ultra-marathoner, never letting her guard down. The majority of ultra-marathons take between one and three days to complete, only the fiercest ones last upwards of a week, such as the Atacama Crossing and the 3,100 mile Transcendence Run in New York.

One of the things that mythology tells us is what we value as a culture. The stories of our epics and our gods is one explanation for why the Indian attitude to sport is primarily bureaucratic, a means of securing (mostly low-level) government jobs, and a ticket to occasional joyrides such as the foreign trip

We have no Pheidippides, who ran from Marathon to Athens to inform the Athenians that they had won in battle against the Persians. His legendary journey, recounted in ….., is the basis for the classic 26 mile marathon, though Phedipiddes himself ran much, much farther. He first ran from Athens to Sparta to request the Spartans for help in the battle with invading Persians, a journey of 150 miles that he covered in 2 days. After a nap and a meal, he ran back to Athens, the same 150 miles to say that the Spartans would take 2 days to join them in war. Knowing Sparta’s reinforcements would be delayed thanks to Pheidippides, the Athenians pulled off a scrappy, unexpected victory over the Persians in Marathon. Pheidippides was then entrusted to convey the good news to Athenians, which he did, and then collapsed dead.

We have no Heracles (Hercules in the Roman pantheon) in our myths either, the patron figure of gymnasiums, pictured in a lionskin and a club. Heracles was a master of martial arts, his success at the twelve labours assigned to him are testimony to his skill, stamina, strength and presence of mind. He was also, like Arjun, a supreme archer who won the right to marry his lover Iole in a contest.

We don’t even have an equivalent of Atlas, who carries the skies on his shoulders, memorialised in unambiguously heroic fashion as a muscular, well-defined man balancing the weight the universe on his shoulders. Indian heroes are not celebrated for such fortitude. If anything, the brave and fortitudinous like Indrajit and Karna and the tribal archer Eklavya lose. In the nineteenth century, the multi-lingual poet Michael Madhusudan Dutt wrote an ode to Indirajit, Meghnad Badh Kabya, considered to be his magnum opus and one of the most famous literary works in Bengali. In it, he celebrated the focus, valour and decency of Meghnad, Ravana’s eldest son, who was killed by Lakshmana when he (Meghnad) was praying. Dutt considered Lakshman’s act a deception. Mainstream interpretations of the Ramayan provide a cover to Lakshman, saying he had not heard Meghnad praying. By mainstream, I mean the most widely circulated. It is easy to pin one version down in this case—the television serial produced by Doordarshan in 1987, and running on air again in 2020.

But these narratives that celebrate the ‘lesser’ characters of the epics, who do the good, decent thing and still lose—say Karna or Meghnad or Sita—are often considered to be influenced by Western thought. Poet Michael Madhusudan Dutt’s legacy, is forever questioned because he converted to Christianity, rejecting Hinduism.

Do these stories matter? Am I attaching too much importance to mythology? I received a “secular”, Western education, there was no Hindu or Greek or Nordic or Persian mythology on the syllabus. It was when I started studying popular Hindi film that I realised how much of an imprint Hindu mythology has on the public imagination, how deeply its motifs and narratives shape the public imagination. For instance, the typical story of brothers who are lost and reunited has strands that are common to the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Krishna, the hero of the Mahabharata, is himself a prince in disguise who is unites with his cousins the Pandavas to defeat the Kauravas, who are another set of cousins. Karna is also a brother of the Pandavas, but unknown to them. Ram and Lakshman in the Ramayana are brothers who are not lost but sent into exile from their kingdom Ayodhya. Peace and prosperity return to Ayodhya when the brothers come home again.

Like cinema, mythology too offers a lens for reading cultural values. I’ve turned often to film in this project to read social attitudes towards women. I’m looking to mythology to read what it suggests about our culture of sport. One way of assessing India’s sport record is by counting our medals and results, that’s the objective way. The subjective way is to look at our stories.

One of the things that mythology tells us is what we value as a culture. The stories of our epics and our gods is one explanation for why the Indian attitude to sport is primarily bureaucratic, a means of securing (mostly low-level) government jobs, and a ticket to occasional joyrides such as the foreign trip. Their individual stories are all affecting narratives of resourcefulness and determination. But their ambition is chiefly clerical, seeking a job with tenure and good benefits. Unlike the Greek myths (which have also shaped the gods of their neighbours, the Romans), we don’t valourise sporting activities in themselves, the expending of physical effort, the shaping of strength, the sculpting of skill. We prefer definitive victories for able-bodied, gifted heroes. We see sport as one of their many gifts, alongside their beauty and willpower and good health and fortune. Their victories feel pre-ordained, someone this good would win anyway, you think, even if they lacked physical strength.

The closest we have to a vigorous action hero is Shakti, the goddess. For more than nine days, she does battle with the buffalo demon alone, and finally defeats him. There is little in common between her and our women athletes except their sex. The goddess was prepped with great care by all the gods. For much of India’s history in international sport, our women have been given nothing except permission to participate. Like Mahishasur, no one expected them to perform, certainly not our infamous sports bureaucracy. But like the goddess who won so memorably that she secured her place among the top drawer of Hindu divinity, these women have extended their memo by far.

Chattopadhyay is the author of The Day I Became a Runner: A Women’s History of India Through the Lens of Sport, published by HarperCollins India