A prominent choral strain in the Kolkata protests against the RG Kar murder and rape is the argument of Bengali Liberal values. “How could such a savage crime against a woman take place in Kolkata?!’

But look back at the history of the 19th century Bengal, and you see a people no more exceptional than the rest of the sub-continent

Case CXXIV: In 1890 in the Calcutta High Court a fully developed Bengali, aged 35, was charged with causing the death as above of his child-wife, a girl aged 11 years and 3 1/2 months…The injury inflicted was a rent in the vaginal wall on the right side of the os uteri, measuring 13/4 inches in length and 1 inch in breadth. Copious hæmmorrhage took place immediately after intercourse. The girl died of exhaustion 13 1/2 hours after the act. The vagina was found to be distended with a clot measuring 3 inches in length by 11/2 inches in breadth, and there was a globular hæmatoma in the right broad ligament, measuring 3 inches in diameter … The evidence in this case clearly established the fact that the fatal injury was caused by sexual intercourse of this mature male, with an immature female, his wife. The court held that when a girl is a wife and above the age of consent (which at that time was only ten years), although it is therefore not rape, still the husband has not the absolute right to enjoy the person of his wife without regard to her safety.” – Queen Empress vs Huree Mohan Mythee, Indian Law Reports, 18 Cal.49; J Wilson, July 1890

In the eight-odd weeks that Kolkata has convulsed with myriad protests against the murder and rape of a doctor in postgraduate training at the RG Kar institute, I have found myself returning to the age of consent legislation of 1891, sparked by the death of Phulmoni Dossee, dead at age of 11 due to penetration by her 35-year-old husband. Prominent in the discourse around the Kolkata protests has been an argument about Bengali progressiveness—a celebratory choral strain actually—that something as heinous as this murder is out of place in Kolkata (and perfectly apiece with Delhi) as well as the fact that only this mad city can rise up in protest so doggedly, angrily, viscerally. That has stuck in my throat. Bengal is not especially progressive when it comes to women or gender. And the history of at least the past 200-odd years proves this amply, a history underlined by colonial reforms on the status of women, almost all of which are associated with Bengali reformers or conditions in Bengal.

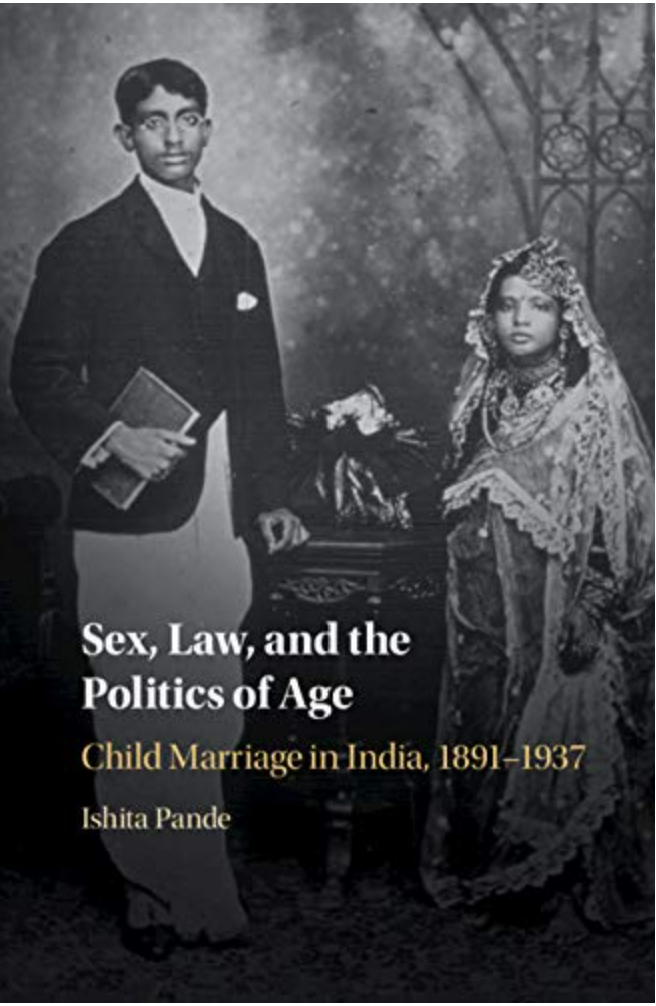

To begin with, the age of consent legislation that raised the age of marriage from 10 to 12. In her outstanding book Sex, Law and the Politics of Age, the historian Ishita Pande argues that this was clearly not consent in the way that we understand it today—the ability to make the choice to have sex with another individual—but actually, permission for a man to have sex with a 12-year-old through the sanctification of marriage. A male license for sex. And Phulmoni Dossee’s case, Pande notes in an earlier paper titled Phulmoni’s Body, was not the only one of its kind, although it is among the most cited cases across British India 19th century in India. In the 1856 edition of The Manual of Medical Jurisprudence, Norman Chevers who served in the medical board of Fort William at the time, noted several instances of ‘rape’ of girl wives of the age of 12 and below, including “the rupture of the hymen and laceration of the perineum and vagina” in an “infant of six. Rape is within quotes because the age was consent for marriage was ten at the time; technically, these would not be rapes in the law of the time.

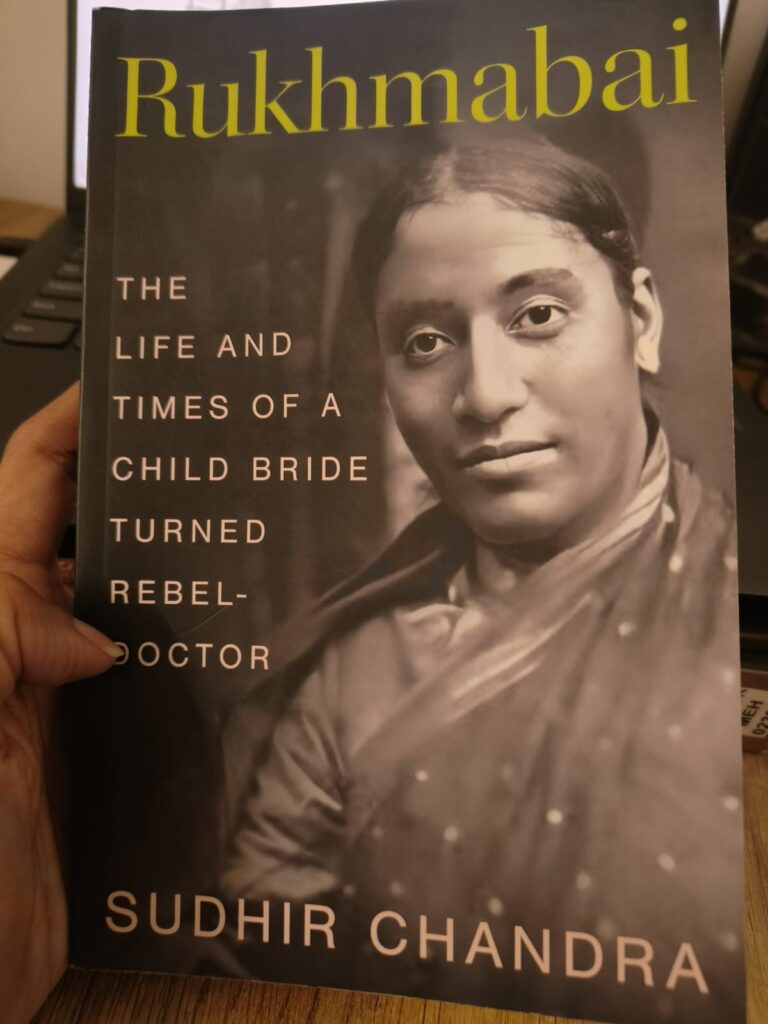

Dadaji Bhikaji vs Rukhmabai Raut 1885-1888

Some years ago in 1885, the doctor Rukhmabai Raut had challenged the validity of a marriage made before a woman can intelligently consent in the case Dadaji Bhikaji versus Rukhmabai, writes the historian Sudhir Chandra in his superb biography Rukhmabai: The Life and Times of a Child Bride Turned Rebel-Doctor. A verdict in her favour was successfully appealed and the court ordered her to live with her husband. Rukhmabai declared instead that she would go to jail for six months, the maximum penalty for not obeying the court’s order rather than live with her husband Dadaji Bhikaji. But this resulted in a compromise verdict, with Rukhmabai having to pay Bhikaji Rs 2000 in return for his not undertaking to execute the decree. Inspite of Rukhmabai’s unprecedented resistance that she would rather go to jail than live with a husband she had not consented to marry and the press attention on the case, it was not enough to get the law changed (even if it played some part).

Pande reads the reception to Phulmoni’s case as the colonizer making an example of cultural exception: ‘look how depraved the natives are.’ An astute reading of the colonial gaze. Child marriage, and hence, the rape of minor girls as we understand it today, was commonplace in Bengali society. What interests me, then, is how a narrative of exceptionalism has been shaped for Bengali progressiveness which rests mainly on the changes during the colonial period. What makes Bengalis seem especially pro-women?

After all, Bengali society of the time did not respond with unanimous agreement to the raising of the age of marriage. There were indeed individuals, including doctors trained in Western medicine, who argued for the age to be raised higher than 12. However, a protest organized at the Shobha Bajaar Rajbari against the 1891 law saw “two to three thousand” attendees, where one of the assertions made was the fathers who married their daughters after puberty would go to hell, writes Pande.

This then was the society Bengal was in the 19th century, described as the age of the Bengal renaissance. In my reading, this nomenclature is entirely thanks to the work and courage of a handful of exceptional individuals. In his outstanding trilogy of historical fiction on this so-called golden age from the mid-18th century to the Partition, the novelist Sunil Gangopadhyay sketches a moving portrait of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s loneliness and resignation in his old age in the second volume Prothom Alo (First Light). Vidyasagar is associated most of all with the legislation to permit the marriage of Hindu widows, passed in 1856. But an energetic practitioner of women’s education (he was principal of the iconic Bethune school and college), he also wrote against the practice of child marriage in Bengali society as far back as 1850. He had signalled his commitment to widow remarriage by organizing the wedding of his son to a widow. But in Ganguly’s finely-researched novel, Bengali society of the day found him annoyingly woke. Widow remarriage had few takers. A common anxiety about the education of girls was that it would make them unmarriageable. If girls could not be married until puberty, was it not like allowing fruit to rot? Those Days and First Light, the first two novels in Ganguly’s Renaissance trilogy both have unforgettable heroines who yearn to study but every social expectation of the time is against this. Ganguly’s research is unambiguous: Vidyasagar had no cache in his lifetime in Bengali society. His elevation has happened retrospectively.

Three points in the personhood of the Indian woman: 1829, 1856 and 1891

The lives of middle-class women in Bengal had changed more rapidly in the course of the 19th century than it had in the centuries earlier, the political scientist Partha Chatterjee writes in his essay ‘Colonialism, Nationalism and the Colonised Woman’. Much, if not all, of colonial reform we study about in school history concerns changes in the lives of women in India. The historian Tanika Sarkar, Pande notes, has succinctly mapped three legislative points that established the personhood of the Indian woman in the 19th century: The Bengal Sati Regulation of 1829 which abolished the practice, the Hindu Widow’s Remarriage Act of 1856, and the Age of Consent Act of 1891.

Each of these has a Bengali association. The abolition of sati is credited to Raja Rammohun Roy although British officers had raised the issue previously. The widow remarriage legislation is attributed to Vidyasagar. And the 1891 age of consent legislation is linked to the body of Phulmoni Dossee.

Perhaps this is what gives shape to the perception of the progressive Bengali?

But this sequence of developments can equally be read to interpret the opposite, isn’t it? Only a rotting society requires a series of reforms, a healthy society would not need this much finger-wagging. I am not being contrarian. My argument is based on the work of historians like Pande, and the literary evidence of Sunil Ganguly’s Bengal Renaissance trilogy and Ashapurna Debi’s unforgettable Bildungsroman Prothom Protisruti where carries among other cruelties, a mention of an 8-year-old bride bludgeoned to death by a grindstone for mixing spices. It serves contemporary Bengalis well to claim a culture of progressiveness from this colonial history, but why should everyone else hum along?

To be clear, I am not making an exception of Bengali regressiveness to argue against Bengali progressiveness. Rather, I am saying that Bengal was (and is) possibly no different from most of the sub-continent. If it has been singled out in the lens of reform it is because of the historical accident of Bengal being the seat of the colonial administration of British India. The heat of the colonial gaze, determined to shame the other, was on Bengal.

It is not so different for the murdered doctor in RG Kar in Kolkata, isn’t it? Pande makes a succinct case for the autoptic truth of the body of Phulmoni Dosee—native Indian society was examined through the post-mortem report of the 11-year-old’s body. What kind of society inflicts this horror on its women, was the question. Here in the RG Kar case, too, forensics is of great interest. It is the government of Bengal is being examined through the forensic report of the young woman. There is obviously something deeply disquieting about this focus—can a social ill be recognized only if unsettling bodily violence is documented?

The opposite perspective—of looking at the body from the lens of society– was less of interest then as it is in this case. Because it suggests a sadly commonplace truth. If you look at rape statistics in the Britain of the 19th century or India of this moment, the crime is anything but exceptional.

Chattopadhyay is the author of The Day I Became a Runner: A Women’s History of India Through the Lens of Sport