50 years of Ankur. 50 years of Shyam Benegal, the anchor of the New Wave movement in Hindi cinema

In that last light of day before it is all gone and the crickets have begun calling, a man hurries through paddy fields swollen with the rain that has fallen all day to a hovel that stands across his sturdy home, the lantern in his hand casting a luminous, almost painterly glow in the darkness. Inside the hovel, in the somewhat brighter light of the stove in the enclosed space, he deflates a bit, as if his eagerness has been caught out. “Who will make the tea?” he asks, looking suddenly embarrassed at the banality of his words. “Who will cook the food? The upkeep of the house—who will do that? Come to work from tomorrow,” he says. And the young woman he addresses can’t help smiling at the man’s artless plea.

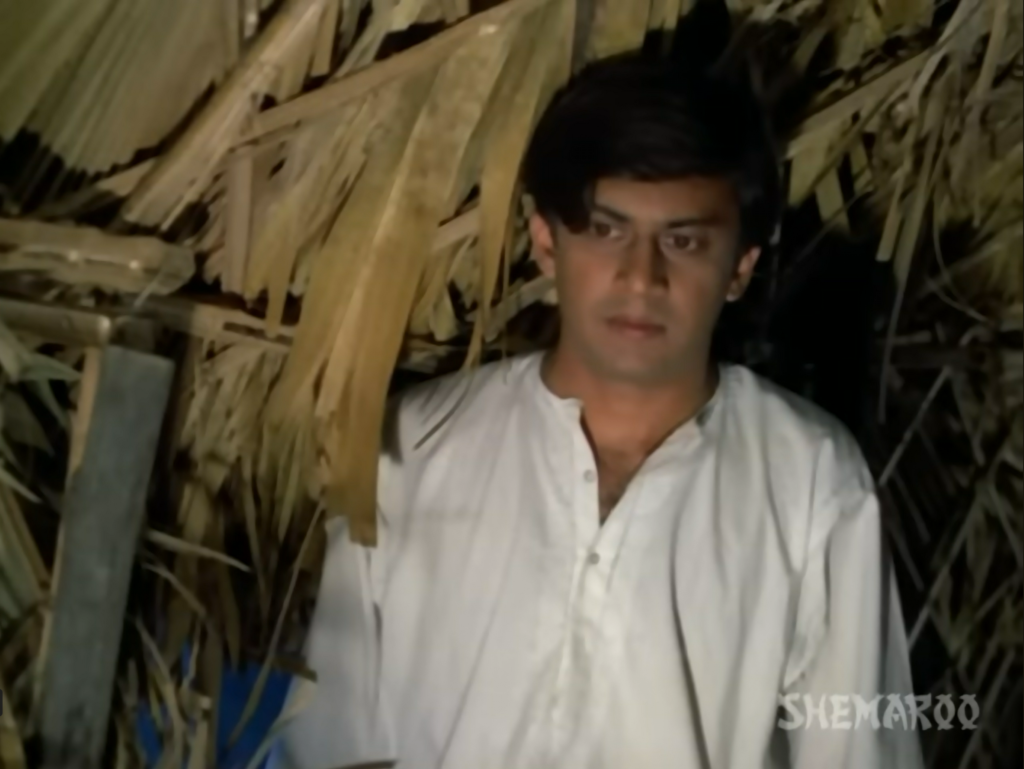

Anant Nag, who plays the impulsive young man, is the son of the big landlord in the village and mostly called sarkar for the duration of his screen time here. It is one of Nag’s first films, he also debuted in a Kannada film called Sankalpa made around the same time. He worked on the stage before this. The young woman he hurries to, Lakshmi, is played by a debutante Shabana Azmi. The year is 1974. It is Shyam Benegal’s debut feature Ankur, based on a newspaper report that Benegal had read about the Telengana Movement of 1946-1951 in which peasants resisted the feudal extortion of landlords who owned obscenely large tracts of land.

The landlord’s young son reluctantly returns from the city—with a third-class degree—and is put to work looking after the estate by his domineering father. Sarkar drives a motorcar through the unpaved muddy roads of the estate and a tyre comes badly stuck in the mud. He listens to songs from the cinema on his LP. The young man is remoulded a little by the changes he has seen in the city: he does not believe in caste he says, although we shall see that this is not as true as he thinks it is.

But he does make it a point to ask Lakshmi, the lower caste*[1] woman who serves him, to cook for him, eschewing the village priest’s offer to send him meals from his home. He is attracted to Lakshmi and enters into a relationship with her that cannot be called consensual, but he speaks with her with kindness. Her husband Kishtaiyya is a deaf-mute potter who has taken to drink, and sarkar assures her that he will take care of her. But he panics when he learns Lakshmi is pregnant with his child. The city-educated landlord wants to be different from his father but finds himself unable to be the man he thought he was, the old ways sucking him in like the slush on the ground slipping, tripping, tricking his beautiful motorcar. When his father, ‘the bade sarkar’, orders his young daughter-in-law to start living with the son, he abandons Lakshmi, pregnant with his child, and without a source of income. The young man’s guilt finds an outlet in Lakshmi’s deaf-mute husband Kistayya: at the film’s close, when he approaches the ‘sarkar’ for a job, delighted that his Lakshmi will be a mother, the sarkar whips him. My reading is that Kistayya is well aware that he is unable to father a child.

The landlord’s anger precipitates a sort of collective breaking point for the village, too. Lakshmi vents, finally, cursing her lover. A small gathering of residents collects to help the couple away. And a young boy flings a stone at a window in the chhote sarkar’s home.

Change is afoot, the malignance of the old feudal ways is more palpable (and ugly) than ever in the democratic light of the long 20th century, and the sense that something is shifting is unmistakeable.

I see the motif of the young man’s desire to be different again and again in the film, including the gorgeous scene where Nag hurries out with the lantern, luminous against the inky black evening. A young landlord tells his lower-caste “servant” that he needs her help, it is an entreaty rather than an instruction, isn’t it?

Or is it the animal gleam of lust that the lantern embodies, sexual desire animating the young man to act impulsively against the grain of everything the monumental patriarchal feudalism of South Asia has shaped him into? Towards the end of this sequence, a snatch of flame in the ‘servant’s’ hut is visible across the glow of the lantern—two bodies drawn to each other by the heat of desire.

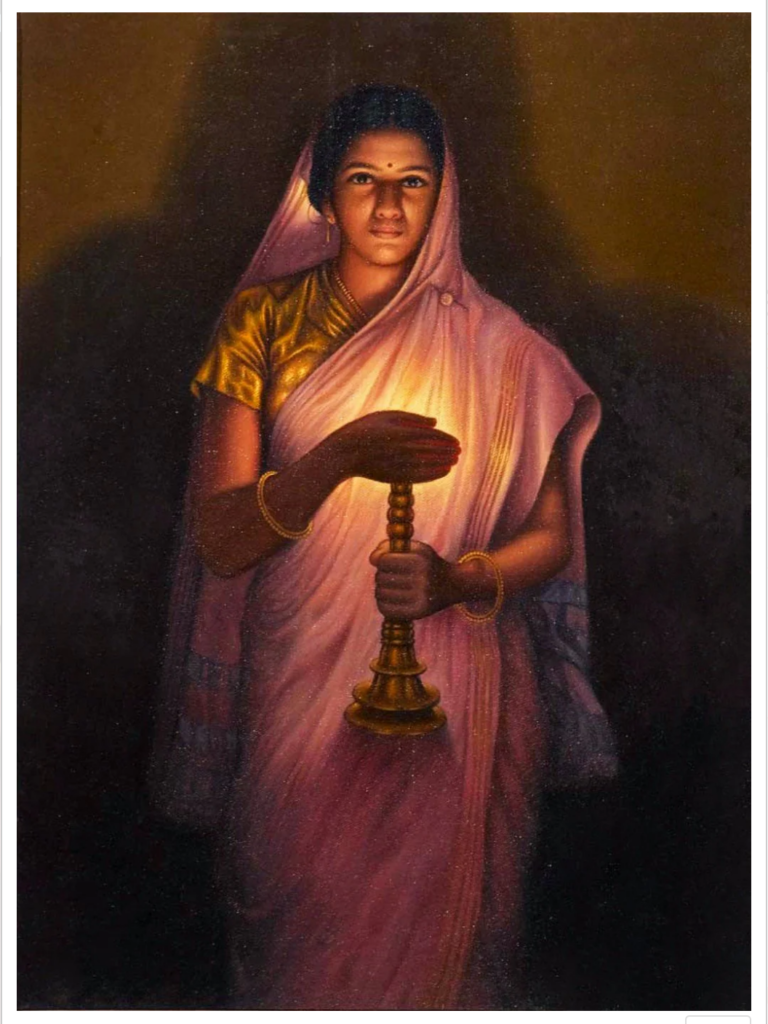

Or is it, simply, the beauty of the image that pulls me—an orb of light darting in the fast falling night towards a flickering flame, illuminating in its wake the outline of a figure in white kurta pyjama. There is a painterly quality to the way the light has been captured in the sequence, bringing to mind that luminous Diwali greeting image (happily) over-shared in our smartphone era—SL Haldankar’s painting titled ‘the woman with the lamp’.

A screenshot of SL Haldankar’s Glow of Hope, alternately titled Lady with the Lamp, taken from the Tallenge store website. Meant for use on my personal website only. No commercial use.

The next year, in Sholay’s quietest and perhaps most critically admired sequence, the white-clad Jaya Bhaduri dims one lantern after another in a cavernous old house while Amitabh plays a melancholic tune on his harmonica in the growing gloom of dusk. The dying of each lamp pushes her face deeper in darkness. The last lantern that Bhaduri carries to her bedroom is extinguished after she lays down on the bed. I find it the opposite of the sequence in Ankur—the extinguishing of desire of a still very young woman, imprisoned in widowhood.

An Indian New Wave

Ankur is regarded as a landmark film in what is known as the Indian New Wave movement dated to the 1970s–the coming together of film professionals trained in the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, and a distinctly non-mainstream aesthetic of filmmaking. What does non-mainstream mean? The prominent use of actors who are not ‘stars’, for one. Smaller budgets that did not rely on established producers, rather this crop of films frequently utilised the funds available from the state, typically NFDC (National Film Development Corporation), raised money from unconventional sources such as donations from milk co-operatives as Benegal did for Manthan. Then, the use of new patterns of editing, shot-taking, sound design including natural sound. Shooting in real-world location rather than on studio sets. And not least, told stories of the lived realities of people—the stories of a society still steeped in feudalism and caste and premodern modes of livelihood, yanked into modernity through a violent colonial experience and an equally violent post-colonial state.

Posters of Ankur, Nishant and Manthan in Benegal’s office in Everest building, Bombay. These three films comprise what I call his rural change trilogy. Photo by me.

When does a set of experimental projects become a movement? My answer is when there is momentum. Stories about contemporary social crises had been made sporadically in the 1940s and 1950s, largely the work of Ipta (or the Indian People’s Theatre Association) members such as Khwaja Ahmad Abbas (Raj Kapoor’s screenwriter), the writer-director Bimal Roy, the playwright and writer Bijon Bhattacharya. But the 1970s saw a certain regularity of such films, likely because there was now a pipeline of film professionals produced by a prestigious institute. Additionally, there was the adoption of a new film idiom at this time—Ipta filmmakers, for instance, shot song and dance in the conventional manner with actors lip-syncing. The New Wave eschewed this.

A more close-to-the-ground approach to storytelling, however, does not necessarily mean serious, or even true to life. Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969), a delightful May December rom-com about a self-important bureaucrat’s (Utpal Dutt) infatuation with a charming young village ‘belle’, is often named as the first film in the Indian New Wave movement. It employs many inventive, winking little touches such as the animated piles of files that grow by the second in a pompous bureaucrat’s office, the pens that start writing in the files by themselves, the telephone that starts echoing ominously and is answered by multiples echoes of said stuffed bureaucrat’s voice. Then there are delicious touches of sound design—the most charming being the delicious tingling of ankle bells accompanying an elegant, long-legged bird’s walk. Not to mention, a superb use of voiceover with the voice that would become iconic to Hindi cinema—Amitabh Bachchan, offering a terrific tongue-in-cheek account of said high-handed babu, ‘who had never allowed his wife a moment of peace in their 25 years of married life’.

The New Wave does not disdain song-and-dance either, but it moves away from the conventional lip-syncing of songs for less literal depictions. And the use of non-stars does not mean that the Indian New Wave cinema lacked in star power—indeed, it developed its own set of stars. In an essay titled ‘An India New Wave’ in the collection ‘Our Films, Their Films’, the filmmaker and writer Satyajit Ray wrote, “…a star is a person on the screen who continues to be expressive and interesting even after he or she has stopped doing anything. This definition does not exclude the rare and lucky breed that gets five or ten lakhs of rupees per film; and it includes anyone who keeps his calm before the camera, projects a personality and evokes empathy. This is a rare breed too, but one has met it in our films. Suhasini Mulay of Bhuvan Shome is such a star; so is Dhritiman Chatterjee of Pratidwandi; so are the two girls of Uski Roti.”

The Star-Actor: The Benegal Cohort of Naseer, Shabana, Smita, Girish Karnad, Mohan Agashe, Om Puri and More

Arguably, Benegal has bequeathed Hindi cinema the largest number of such stars, ‘stars’ who were known most of all for their acting chops, stars who were not defined by looks (or mannerisms) that befit matinee idols. Which is not to say they were not attractive, or to suggest that mainstream Hindi film actors were not good actors. But this cohort, the class of Benegal so to speak, came trained in performing, aided by the setting up on acting programmes in the National School of Drama and the Film and Television Institute of India. Who comprised the Cohort of Benegal? Off the top off my head–Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, Amrish Puri, Om Puri, Amrish Puri, Mohan Agashe, Dina Pathak, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, to name an incomplete list.

Hasn’t each of these gone on to produce incandescent performances in Bollywood[2] too? If you can imagine Bollywood without Smita Patil, then you are thinking of a firmament where Bachchan and Smita set Bombay aflame on a night that pours (‘Aaj rapat jaaye toh humein naa uthaiyo’). If you can think of Bollywood without Shabana Azmi, then you are thinking of a world without the madcap joy of Amar Akbar Anthony. And Naseer and Amrish Puri? Imagine passing through this life without having those eyes burning themselves onto our memories? Or, living a few centimeters away from our skin, some inches removed from our hearts.

Ankur is Azmi’s first full-fledged film performance, a complex, central role of a young woman who gives in to desire knowing well the devastating consequences it may have. I say full-fledged because as a graduate of FTII, she must have performed for student graduation projects. Even in a career as rich as hers, it is hard to think of a performance as controlled and bursting with life as this. Shining with love, overflowing with loneliness, still and quiet as a stone. A dam swelling threateningly close to danger point. She is Lakshmi, an untouchable agricultural worker married to a mute drunk whom she mothers like her child, in love with the charismatic, handsome young landlord who treats her with dignity and desire before slipping back into the sludge of centuries-old feudal habits.

A husband like a child and love in other places is a situation that is not unfamiliar to women in the subcontinent. Many stories have mined the emotional vulnerability of this situation. Shabana plays Lakshmi without a milligram of self-pity, with the accumulated wisdom of centuries of knowing her place in this feudal world, and the management of the attendant macro-and micro-humiliations that come with it. Remarkably, there is no knowingness in her Lakshmi—the sense of cynicism or scorn that comes from knowing disappointment well–but an openness to life and the little pleasures it has to offer. She’ll take her chances with what she wants, because her heart has learned how to field everything this life has thrown at her. At the end, when Lakshmi finally vents her anger, you feel the pressure of the dam wall giving away.

Azmi would go on to do seven feature films with Benegal—these include his most celebrated works such as Nishant, Mandi and Junoon (aside from Ankur), and build a formidable career that enjoyed a good number of mainstream releases.

The Non-Acting Professionals: Messrs Govind Nihalani, Ashok Mehta, Vanraj Bhatia, Shama Zaidi, Satyadev Dubey

But it wasn’t only such actors that Benegal bequeathed to mainstream Hindi cinema. His legacy is also the outstanding non-acting professionals he introduced. Ankur marks the second film (going by IMDb) of cinematographer and director Govind Nihalini, writer Satyadev Dubey, and the debut of composer Vanraj Bhatia—collaborators he would work with throughout his career, whose work was frequently commissioned by Bollywood. Other frequent collaborators were the screenwriter Shama Zaidi (who has written iconic films like Garm Hava and Umrao Jaan) and the cinematographer Ashok Mehta, who like Azmi went on to be successful in the mainstream industry as well. But Mehta has done some of his best work for Benegal. Nihalini chose to be more selective with his mainstream commissions.

Then again, think of the lamp extinguishing sequence in Sholay. Once you have seen Ankur which released in 1974, it’s hard not to think of Nihalini. Sholay released in 1975.

Benegal was a force of nature, but it was also a terrific, rich season of cinema. Graduating batches from the two institutes, particularly the FTII, facilitated a pipeline of superb fresh film talent. Directors like Kundan Shah, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Ketan Mehta and Saeed Akhtar Mirza were all FTII graduates, although Benegal himself was not. Each of these directors has made unforgettable films—Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron (Shah, 1983), Mirch Masala (Mehta, 1987), Khamosh (1986) to name one of Vinod Chopra’s before he branched into more mainstream work, Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyun Aata Hai (Mirza, 1980). But no one has worked as prolifically and as firmly in the new wave idiom as Benegal has. In this sense, it is truly he who is the father, or shall we say anchor, of the Indian New Wave movement.

The Purple Patch

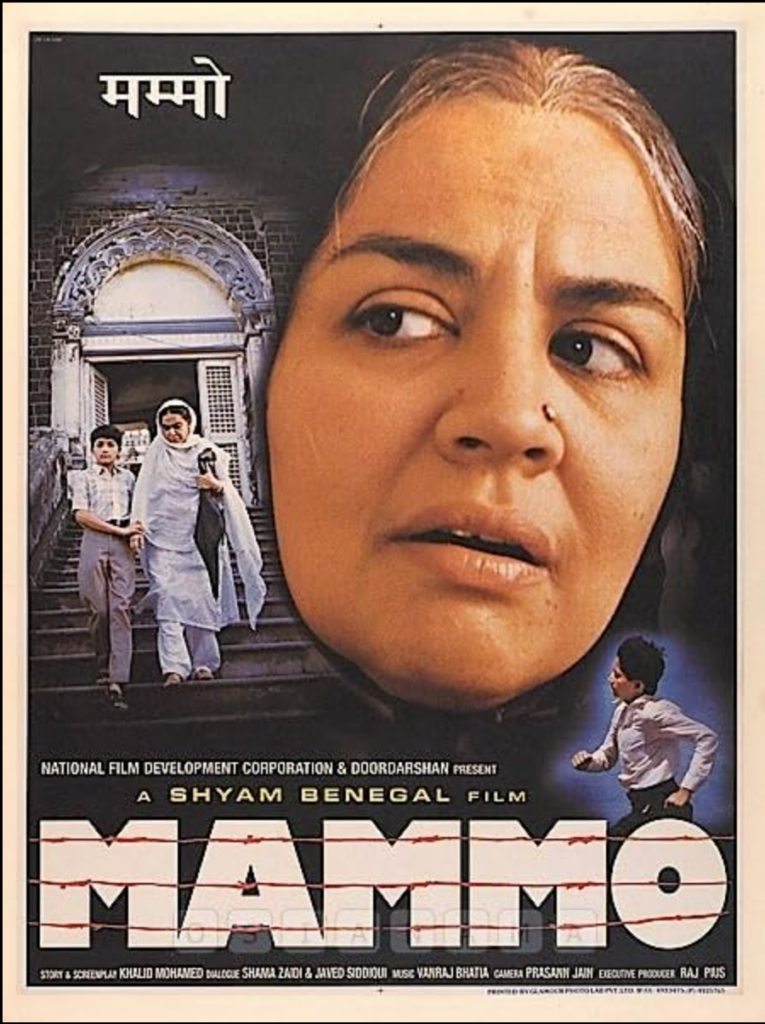

Ankur marked the start of a terrifically fertile decade and a half of filmmaking by Shyam Benegal Nishant followed in 1975, Naseeruddin Shah’s screen debut (he had appeared in a non-speaking role in Aman), Charandas Chor also in 1975, Manthan in 1976, Bhumika in 1977, the Telugu language film Kondura (Anugraham in Hindi) in 1978, Junoon in 1979, Kalyug in 1981, Mandi and Arohan both in 1983, Trikal in 1985, Susman in 1987 and three major TV serials in the late ‘80s including the sprawling 53-episode Bharat Ek Khoj series based on The Discovery of India by Jawaharlal Nehru. In fact, Benegal averaged his amazing pace of one project per year and a half, until the mid-1990s including ambitious films like The Making of the Mahatma, and the delightful Mammo.

But it was in the ’70s and early ’80s that Benegal made the films he is known for: Nishant and Manthan complete his trilogy of rural change, Bhumika is a superb complex biopic on the Marathi screen legend Hansa Wadkar, Junoon (based on Ruskin Bond’s novel A Flight of Pigeons) is celebrated for being one of the first films to seriously depict the chapter of the revolt of 1857, Kalyug is a contemporary imagining of the Mahabharat, and Mandi is an outrageously funny social satire. These are ambitious projects, taking on the prospect of telling complex and prominent stories of India—the revolt of 1857, the epic Mahabharata, the 20th century stirrings in India’s deeply feudal heart (the rural change trilogy), a series based on Nehru’s best-known book.

As socially committed and idealistic as Benegal is, he also has a zany sense of fun. He injects humour in unexpected places, suggesting that life itself is unexpected and funny, even the hardest, most deprived lives are not bereft of the possibility of lightness and laughs.

The Indian Hindi New Wave

The year 1969 is marked as the start of the Indian New Wave: aside from Bhuvan Shome, there was Uski Roti by Mani Kaul, a director who trained in the Film and Television Institute of India. Kaul made a handful of features including Duvidha which was reworked as Paheli with Shah Rukh Khan, and several documentaries after this. Mrinal Sen had made several films before Bhuvan Shome. Why 1969? In part because the term French New Wave, associated with Francois Truffaut, Jean Luc-Godard, Alain Resnais, Claude Chabrol and Louis Malle had gathered currency in the 1960s. The mark of some of their influential experiments—jerky, swift edit patterns from Godard’s Breathless for instance, the choice of prickly, not entirely likeable protagonists—is evident in the Indian New Wave. We see this in Bhuvan Shome, the titular character is a pompous clown. The heroine, Gauri, is a delicious charmer who believes bribes are a matter of right for salaried employees. Benegal’s filmography is full of wonderfully complex protagonists—not just Azmi in Ankur, but Nag’s young landlord is a decent man undone by cowardice.

But the term Indian New Wave is a mislabelling. What began in 1969 is really the Hindi New Wave movement. When he made Bhuvan Shome in 1969, Sen was already an established experimenter. even if BS was his first box office success. He is a contemporary of Satyajit Ray whose debut Pather Panchali, released in 1955, marked a natural and astoundingly moving style of filmmaking in India, and brought Indian cinema a degree of international renown that it had not seen until then. Sen would make his debut the same year with Raat Bhore, and go on to build a career that enshrined him in the holy trinity of the film school community of India—Ray, Ghatak, Sen. Pather Panchali is made in the Italian neo-realist style. Sen experimented more with the playful French new wave style of Godard, Truffaut, Resnais and others. And Ghatak went in the opposite direction—employing folk melodrama style storytelling to craft crushing portrayals of poverty and the crisis of human dignity in post-Independence India. All three worked on stories of social crisis set in grounded realities, and they are only the best-known ones.

I don’t say this to claim Bengali primacy in the movement (hard as that may be to believe). It is likely, rather, that there were similar experiments underway in the other filmmaking centres in India–erstwhile Madras, Kerala and Bombay. In fact, India’s first Cannes win went to the Hindi film Neecha Nagar by Chetan Anand** (alongside eight other films), a story about caste. In other words, several new waves were possibly underway in India when the movement that is given the honour of capital letters began in Hindi film in the 1970s.

Why was this movement called the Indian New Wave and not the others? I would argue, language. Hindi was and is projected as the national language, even if it is not technically the national language. The National Movement certainly projected Hindi as the language of a new national unity. In real terms, the Bombay film industry has long served to project the hopes and vision of New Delhi, the political capital of India. Through this lens of language politics, the nomenclature of Indian new wave for a Hindi film movement is correct.

What happened to the New Wave?

Did the New Wave subside? It is perceived that by the second half of the 1980s, the movement had run out of steam. Chopra made the tremendously successful (and compelling) Parinda with three mainstream stars—Anil Kapoor, Jackie Shroff and Madhuri Dixit. Chopra’s previous, Khamosh (1986), now rated as a superb thriller, had found no producers. Despite the tremendous acclaim for Mirch Masala, Ketan Mehta would manage to make his next film Maya Memsaab (an adaptation of Madame Bovary) only in 1993. Kundan Shah would make Kabhi Haan Kabhi Naa, a charming comedy starring Shah Rukh Khan and Deepak Tijori, only in 1994.

Benegal alone continued to make films at his old pace of one film every one and a half years until 1998, more than one decade after Chopra, Mehta, Mirza and Shah had largely stopped working in the idiom. He made 7 feature films between 1987 and 1998. He launched the career of another star actor in this decade, Rajit Kapoor, who like his other acting proteges has gone on to build an enviable filmography in mainstream and non-mainstream cinema.

I remember at least three of these being projects that received reasonable play on television—the Making of the Mahtama, Mammo and Sardari Begum. They may lack the prestige and power of his work as a director in the decade between the mid 1970s and ’80s—his first, purple, decade as a director. On what basis do I say this? The arguably subjective basis of reputation. Benegal’s films in this first decade—the rural change trilogy, Bhumika, Junoon, Mandi, Kalyug, are the ones that appear to have the most recall value.

In 2001, Benegal cast the 1990s superstar Karisma Kapoor in Zubeida and the iconic Rekha in a smaller part, along with his usuals Amrish Puri, Surekha Sikri, Rajit Kapoor, not to mention the composer AR Rahman with whom he worked for the first time. Was this the signal that the New Wave was dead?

Or had it been dead for more than a decade by then, when Chopra and Shah and Mehta and Mirza had run out of energy. Had Benegal alone had kept it alive like a lifesaving machine working overtime on an aging, bloodless body?

The scholar Vikrant Dadawala (2022) dates the death of the movement to the mid-90s in his superb paper ‘Literature, Print Culture and the Indian New Wave’. The actor Naseeruddin Shah, icon shaped by the Hindi New Wave, holds that the wave was over by the late 80s. My own sense is closer to the perspective of the film critics Uday Bhatia and Jai Arjun Singh who brought out a thoughtful list of 50 films to mark 50 years of the Indian New Wave. This list continues well into the 2000s, and Noughties, ending with Soni, a film that came out in 2019—that is the year they wrote this list.

If you were to see the New Wave movement through a set of defined parameters that include state/NFDC funding, the casting of stars who are not from the mainstream, a certain social commitment to social consciousness, then the evidence is undeniable: The New Wave was dying by the late 1980s and dead in the mid-1990s.

But if you were to see the movement as a set of ideas that shaped a generation of later writer-directors like Anurag Kashyap and Tigmanshu Dhulia and Kanu Behl and Ritesh Batra, who found a place first through the indie film and now through the OTT ecosystem, then the New Wave is very much around us still. Think of the actors and stories on OTT. In fact, think of the careers of Naseeruddin and Shabana and Smita and Om Puri and Amrish Puri in Bollywood, and the Irrfans and Konkona Sen Sharmas and Nawazuddin Siddiquis that Bollywood has hungrily sought after them. If anything, the New Wave has reshaped mainstream Hindi film. And Benegal had a lot to do with it.

A screengrab from the Youtube print of Ankur: the memorable last sequence of the film, where a boy flings a stone at the young landlord’s home. A boy who, minutes ago, had been flying a kite with the landlord.

I find myself returning often to the last scene in Ankur—a boy flings a stone at the young zamindar’s home and runs away. The first move had been made. I think of Benegal filming the shot, and I see him waiting and watching long after the unit has packed up for the day. I think of him as the man who cast a stone and made us open a window, and kept waiting and working patiently till we stepped out to see what was afoot.

“Shyam told me to just move my eyeballs to convey lust. Just follow the movement of the woman”: Naseeruddin Shah

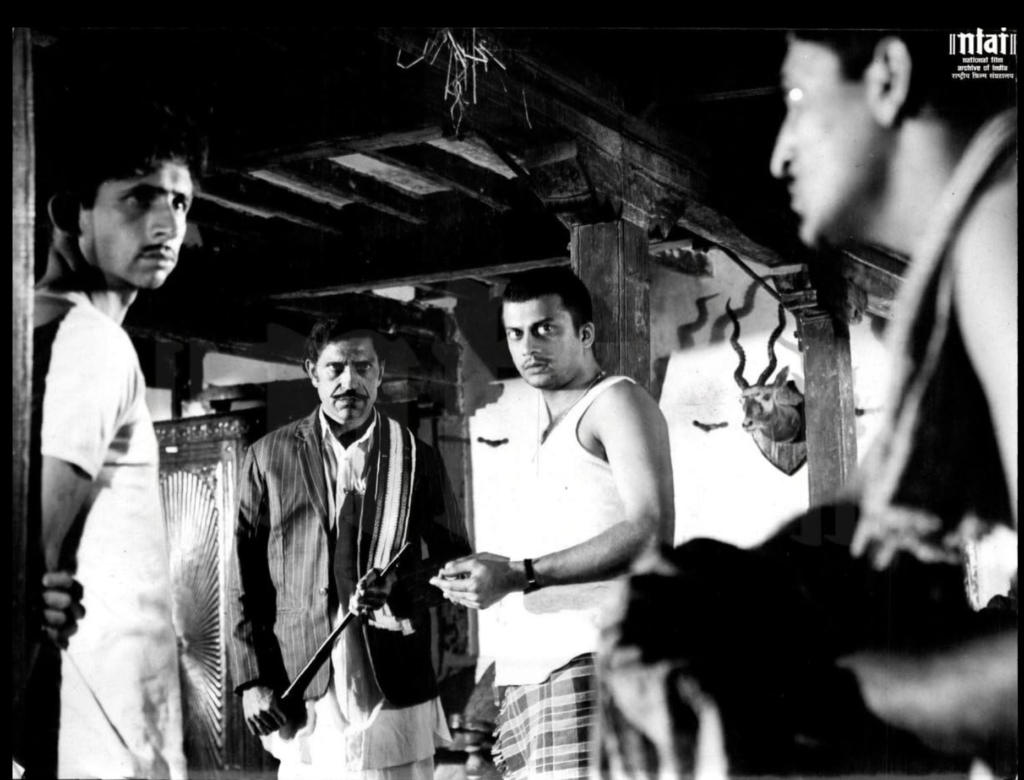

In this still from Nishant (1975), facing us in the photograph are Naseeruddin Shah (left), Amrish Puri (middle) and Anant Nag (right). This is Shah’s real screen debut.

“I watched Ankur in a packed theatre in Kanpur. I think Bobby had also opened at the same time, and some people would say that people had come out to watch Bobby and when they couldn’t get tickets, they didn’t want to go home so they came for Ankur. Even if that were true, I remember them following the film intently, they were listening, they were not walking out, not restless. I was still a student in the film institute then, in my second year. And I was thinking, ‘This is the sort of film I can do. Because nobody would come to watch me dance or romance. I never had that kind of face.’

Later I went to meet Mr Benegal and I was told I would have a role in his next film, which turned out to be Nishant…

Shyam made it possible for a whole bunch of us to have careers—me, Smita, Om, Amrish, Mohan [Agashe], Kulbhushan [Kharbanda], Shabana. I don’t know of any other director who launched so many actors. Only Shabana among us could have made it anyway. She knew people in the industry.

He taught me how to act in cinema. He told me, I just had to perform for the camera. I remember one time I was supposed to lust after a woman. I wasn’t getting it. He told me, ‘Just move your eyeballs. Follow the woman with your eyes.’ When I saw the shot later, I had to agree. It was very effective!

–Naseeruddin Shah is an actor, considered to be a legend of the Hindi film screen along with the likes of Dilip Kumar, Nutan, Balraj Sahni, Amitabh Bachchan, Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil.

“Ankur’s unexpected success led to a whole cohort of Hindi films in the 1970s and 1980s that responded to outbreaks of agrarian violence”: Vikrant Dadawala

Fifty years later, Anant Nag remains strangely compelling as the insincere and vacillating Surya in Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (1974), whose rakish hair and sunglasses mark him as an outsider on his father’s feudal estate. “Mein jaat paat nahi manta (“I do not believe in caste”),” Surya declares to Lakshmi, played by Shabana Azmi. But this is bunkum. The landlord’s son may want to be modern, but when faced with the consequences of his actions, panic and fear drive him towards old forms of cruelty. While Azmi’s debut performance is the one people usually remember, it is Nag’s eyes that capture the despair and confusion of a defeated man slowly turning into a caricature of his boorish father. Meanwhile, Govind Nihalani’s camera tracks and pans over Telangana’s rocky landscape, hinting at a larger world outside the frame: women singing as they bend over paddy fields; wandering ascetics at twilight; recurrent images of coconut trees, trembling in the wind, indifferent to human concerns. The drama taking shape under the trees may be sordid, even predictable, but you can’t look away. This is real, the trees seem to whisper.

As Ankur moves towards a conclusion, all possible happy endings seem to be closed-off by history. The fantasy of a redemptive arc for Anant Nag’s character fades away, Azmi’s character is used and then cruelly abandoned, the mood in the village shifts from servility and acceptance towards sullen anger. The film concludes with a subdued act of revolt. How else could it end? The Naxalites were already active in Telangana when the film was being shot. Ankur’s famous last scene depicts a boy throwing a stone at the landlord’s house. This scene, shot from behind, is a quiet precursor to a similar scene in Nagraj Manjule’s Fandry (2013), except, in Manjule’s 2013 film, the stone is thrown straight at the camera, and at us as viewers.

In retrospect, Ankur is neither as angry as Fandry, nor as lyrical as Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) — like many New Wave films, it lands somewhere in the middle. But Ankur’s unexpected success led the way for a whole cohort of Hindi films in the 1970s and 1980s that responded to outbreaks of agrarian violence in places as far apart as Telangana and Bihar. When I was a student at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai, I used to come across fact-finding reports on rural violence or caste atrocities from the 1970s gathering dust in the library shelves — nobody in my generation was interested in those documents, or in the forgotten struggles they documented. In that sense, Ankur is a great example of how art can outlive its moment. Although Shyam Benegal’s cinema could be preachy at times — Manthan (1976), made during the height of the Emergency, feels synthetic and contrived to me — his best work forces you to confront reality by learning to see things as they really are rather than as you might want them to be. This unraveling of the urban audience’s illusions may be the real legacy of Ankur. What looks like an angry film is more introspective than we might initially assume. I think we still have much to learn from Ankur and the films that followed in its path, such as Benegal’s own Nishant (1975), Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh 1980), and, my own favorite in this genre, Gautam Ghose’s Paar (1984).

–Vikrant Dadawala is an assistant professor in York University

“nuanced depiction of caste…Shabana plays a Kumhar, an OBC caste, not Dalit as many reviewers misunderstood”: Manoj Mitta

Growing up in Hyderabad, one of my fondest childhood memories is watching along with my father this Telangana-based movie called Ankur in 1974 when it was newly released. My excitement at the time was over just the novelty of seeing a Hindi movie that captured the cultural idiosyncrasies of Hyderabad. Besides being aware since then that this debut work of Shyam Benegal is a landmark in the history of Indian cinema, I have long taken pride in sharing space with him in the alumni of Nizam College in Hyderabad (even if we were separated by decades).

When I watched Ankur again in 2024, in the 50th year of its release, I discovered more layers to the feudal life depicted of the Hyderabad princely state of around 1945. This is especially because I have recently written a book on the legal complexities of caste. One such complexity brought out in the movie in a nuanced manner is that the discrimination against lower castes is not necessarily about ‘untouchability’ as understood in law or even popular culture.

Though it made clear that the character played by Shabana Azmi was a Kumhar, which is an OBC caste traditionally engaged in pottery, many reviewers mistook the discrimination suffered by her for untouchability. Had she instead been portrayed as a Dalit in that very feudal setup, there was no way she could have, for instance, drawn drinking water from a well for the landlord played by Anant Nag and his wife played by Priya Tendulkar. That the lower castes other than Dalits also faced discrimination in varying degrees and forms, and that this is despite their constituting a majority of Hindus (or even Indians), is still a little known irony of our society.

I agree with the general perception though that the grey shades of Ankur’s protagonist betray a deeply ingrained intersection of caste, class and patriarchy. The movie stands the test of time because such a conflict between rhetoric and reality is as manifest as ever in those who are liberal more out of expediency than out of any courage of conviction.

–Manoj Mitta is a journalist and writer, most recently of the book Caste Pride, Battles for Equality in Hindu India, published by Westland

“Benegal draws out a unforgettable portrait of systemic oppression—a moment that could easily exist in the pages of a great Indian novel”: Raja Sen

Some films have always felt more like books. When a film transcends mere storytelling and luxuriates in the sprawling depth of its characters, when scenes unfurl with the intimacy of prose, rich in subtext and consequence, that’s when cinema becomes literature. It’s a novel, but alive, breathing between frames, dense with thought, ambition, and emotion. Silences — like those formed between lines or between the turning of pages — speak.

One scene from Ankur exemplifies Shyam Benegal’s genius for weaving social subtext into intimate moments, creating cinema that feels as richly textured as a novel. The scene in question—Lakshmi (Shabana Azmi), a Dalit woman, fetching water under the gaze of the village landlord’s son Surya (Anant Nag)—is deceptively simple but layered with meaning.

Lakshmi, dressed in the earthy tones of a woman tied to the soil, moves with practiced precision. As she draws water from the well, the camera fills each frame with subtext. This isn’t about water; it’s about power and caste. The act of drawing water, a symbol of sustenance and survival, becomes a metaphor for Lakshmi’s entrapment in a system that limits her access to both. Surya, watching her with increasing interest, represents a more modern India—educated, progressive on the surface, yet complicit in the structural inequalities that persist. He’s drawn to her but not in a way that challenges the hierarchy—only in ways that gratify his own desires.

The scene unfolds with quiet, literary grace, as Benegal gives us room to consider the unspoken: Lakshmi’s dignity in her everyday toil, Surya’s unearned privilege, and the invisible weight of the social order bearing down on them both. Lakshmi remains outwardly stoic, and Benegal, much like a novelist, lets the audience sense her suppressed agency. We can see the layers beneath her silence—the history, the suffering, the pride.

Another devastating scene sees Lakshmi being accused of theft. Here Benegal the novelist layers indignity, injustice, and raw humanity into an interaction that feels at once inevitable and deeply personal. Here Lakshmi stands before her landlord Surya, the man she once trusted and served, who now looks at her through the prism of suspicion. It’s not merely the accusation that stings but the way it encapsulates the brutal intersection of class, caste, and gender. Lakshmi, a Dalit woman, has no voice, no defence. In this small, contained moment, Benegal draws out a unforgettable portrait of systemic oppression—a moment that could easily exist in the pages of a great Indian novel.

Azmi’s performance is riveting yet spare. She stands still, her eyes widening in disbelief as Surya’s wife Saru (Priya Tendulkar), from her higher-caste pedestal, demands answers, convinced of Lakshmi’s guilt. Benegal is as restrained as Azmi, letting the moment speak. Lakshmi, wronged and helpless, does not erupt. Instead, her face speaks volumes—the injustice of being accused by those more powerful, the futility of resistance, and the anger that bubbles beneath.

The audience is drawn not just into Lakshmi’s pain, but into the layers of historical and societal wrongs that make this moment unavoidable. Surya, who once engaged in an illicit affair with her, now refuses to defend her, revealing his cowardice and the tenuousness of his supposedly modern values. The scene functions not just as a pivotal moment in Lakshmi’s personal story, but as an indictment of the entrenched systems that reduce people like her to mere objects in the hands of the powerful.

It is this social critique—disguised within the personal—that gives Ankur its unforgettable, literary quality. For a first-time filmmaker to have such control and storytelling restraint… It is a thing of beauty, and, like many a hero from a novel, nearly too good to be true.

–Raja Sen is a screenwriter, critic and author of The Best Baker in the World, published by Penguin India

[1] I had interpreted Lakshmi’s character to be Dalit. The writer Manoj Mitta’s comment on Ankur, invited for this essay, made me aware that Lakshmi is likely from the potter caste, which is not untouchable. Mitta is the author of the outstanding legal history of caste battles in India, titled Caste Pride: Battles for Equality in Hindu India.

[2] I use the term to mean commercially-minded Hindi cinema with big stars, big budgets, song-and-dance and a certain masala storytelling, not as an unthinking synonym for Hindi language cinema as is sometimes (frequently).

[3] An earlier version of the post incorrectly mentioned Vijay Anand as the director of Neecha Nagar. It is Chetan Anand.

[SC1]https://bangaloremirror.indiatimes.com/bangalore/others/how-a-woman-with-a-lamp-turned-a-plain-canvas-into-a-masterpiece/articleshow/50033938.cms