The lives of those who collect our trash, serve our meals and drive our vehicles are in focus again. The Hindi film has returned to working class concerns

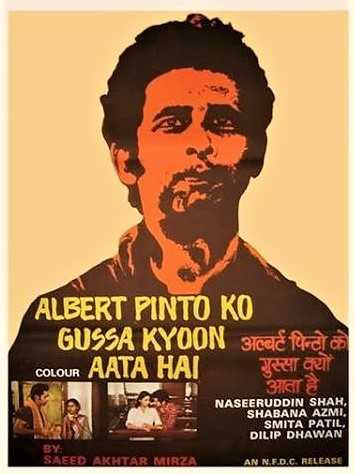

In April, a film called Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyun Aata Hai? arrived, a reimagining of the 1980 film starring Naseeruddin Shah in a Mumbai that was still a city of blue-collar workers. In the new film, the actor Manav Kaul is not a blue-collar worker but a former corporate employee disgusted by the corruption in the corporate world. He chucks his job to become a hitman.

On the surface, there is no labour or employment angle. But think of what happened in the real Mumbai in the 1970s and 1980s—as the mills closed and workers lost their jobs, they were drawn into the murkier world of real estate and politics. It is a world we see in the “underworld” films of the 1990s, where the most memorable characters like Bhiku Mhatre, Chandu, Raghu were all gangsters in films like Satya, Company and Vaastav. When the so-called real economy has no jobs, or whatever it offers disgusts you, what do you do?

In the original film, Shah is a car mechanic who is frequently cross. His father is a mill worker, and Albert is initially angry with him and the city’s frequent strikes. He finds himself agreeing with his rich clients that workers should not strike. His younger brother is a gunda, the most frequent form of employment we see in the angry Mumbai films from the 1970s to the underworld films of the 1990s and Noughties. Later, when he starts listening to his father’s reasons for striking, he is justly angry at how the rich squeeze the working class dry.

The new Albert Pinto film sank, unlike the older one which is something of a cult classic. But the new film felt like a pointer to what was happening in reality, a little detail that assumes significance in retrospect. Some weeks after the film released, the Bharatiya Janata Party government, which returned to power with a big victory in May, released data on jobs that it had earlier refused to confirm, saying it was still being processed. Unemployment was at a 45-year-high. The Albert Pinto of 1980 didn’t seem that far away.

In Super 30, released on 12 July, Hrithik Roshan plays the real-life teacher Anand Kumar, who tutors children of “garbage collectors, bus drivers, salt factory workers”, essentially the children of Albert Pintos—blue-collar workers who get paid for manual work. Four decades ago, they might have enjoyed greater respect, with unions defending their interests, and better prospects for their children. Now their sole identity is that they are poor, dependent on a messiah like Kumar to make something of their lives.

The film is the fictionalized story of the coaching class pioneer, Kumar, whose eponymous programme has claimed stunning success in sending poor children to the Indian Institutes of Technology.

Not one of the 30 students in the film has a developed arc, once the film is over it is hard to remember which one of them wanted to be a marine architect, which one a mechanical engineer, and which one was the mandatory US space agency Nasa aspirant. They are simply background props for the messiah act. They get one song—significant real estate in a Hindi film—but it is embarrassingly bad, ruining a nice line from Sholay. It caricatures the kids, giving them darkened glum faces and third-rate ideas. (changed slightly)

Still, the film does get one thing right—in a contemporary moment of zero opportunities and extreme class silos, it identifies the fact that you need a messiah for social mobility. Education in itself is not enough.

Who are the working class? For one, blue-collar work does not require university-degree qualifications. Second, workers are paid by shift or day, not monthly salaries. A third point, I think, is house ownership—the working class can’t afford a home in the city, the middle class and above can.

In June, there was Bharat with Salman Khan. In the trailer, he appeared as a motorcycle stuntman, a miner, a marine man, and I imagined that like most Khan films, finding employment would not be a problem. But the longest thread in the film is that of unemployment. In the 1960s, Bharat stands in queues outside employment bureau to no effect until news arrives that oil has been found in the Arab countries. He leaves for an oil and gas rig job, and the film briefly looks at migrant labour tensions between developed (white) and developing countries.

After his return from the rig, Bharat takes off on a merchant navy ship to earn money. Three-quarters into the film, Bharat’s voice-over says the heroes of the 1990s included then finance minister Manmohan Singh, who liberalized the Indian economy and improved work opportunities. I never thought I would talk about labour tensions, the economy and Salman Khan in the same essay. In truth, the mainstream Hindi film’s engagement with labour issues had long receded.

Working-class concerns featured in the Hindi films of the 1950s—in Naya Daur, where Dilip Kumar unionized tonga workers to oppose a bus service (automation), and Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin, where landless labourers come to work in the city and are crushed by its apathy. Then there was a period in the 1970s when strikes and unions featured in Amitabh Bachchan films like Deewaar, Kaala Patthar and Namak Haraam. The 1970s were, in fact, the years when everything was running aground–India was recovering from a war with Pakistan, the birth of a new country that led to millions of refugees pouring in, the Air India and labour strikes across the country, the unfolding of the Naxal movement and its bloodied clampdown, and in 1975, Mrs Indira Gandhi declared an Emergency. Hindi films reflected these anxieties. Perhaps the last mainstream film that highlighted the concerns of the urban working class was Coolie (1983), where Bachchan is the leader of railway porters.

Thereafter, as India Liberalized in 1991, the Hindi film turned wholly away from practical concerns towards romantic ideals like love, nationalism, justice (Damini,where a woman fights for a rape survivor), and family (Parinda, Hum, Hum Aapke Hain Koun..!). Mostly though, it was grand, sweeping love that occupied Hindi film from the 1980s onwards, especially as the careers of the three Khans, eternal lover boys, took off. In fact, the Khans and subsequent A-listers have played working-class characters so rarely that the exceptions spring to mind—Aamir Khan is a taxi driver in Raja Hindustani, Hrithik Roshan is a salesman in Kaho Naa… Pyaar Hai, as is Ranbir Kapoor in Rocket Singh: Salesman Of The Year (arguably salesmanship is not blue-collar work because salesmen earn commissions over a salary).

But Bollywood gets the pulse of public sentiment instinctively, in a way it is rarely credited for. The return of working-class concerns comes with the real-time return of economic anxieties borne out by data. Much of this year’s Gully Boy is set in Dharavi, a story of lives that barely have place in the formal economy. Hero Ranveer Singh’s father is a driver, his step mother is a domestic worker, his friend is a mechanic who steals cars and peddles drugs on the side. “Your father is a driver. A servant’s son becomes a servant,” Singh’s businessman uncle tells him, although he is studying for an MBA. There is a similar line in Super 30, as if the conversation were being continued there: “The king’s son will no longer be king, only the deserving shall be king,” Roshan tells his students. The driver’s son (or daughter) no longer has to be the servant, he implies.

Singh stumbles on to the local hip hop scene in Gully Boy, finds a mentor and becomes a breakout star. He is a gifted writer, and good luck and the internet facilitate his route out of his dead-end life. As his luck changes, his mechanic friend is locked up in jail. I read this as a statement of how opportunities remain locked for those without talent and luck. Super 30 shares this worldview—a boy who fails the cut-off by one mark is sent away because he needs to understand the chasm between making it and falling short. You have to be terrific to make to the Super 30, and you have to find a genius mentor.

With its setting in music, Fanney Khan is more of a companion piece to Gully Boy. Here, the heroine’s father, played by Anil Kapoor, works as a taxi driver after losing his factory job. The family lives in a chawl, the mill-worker accommodation that once dotted south Mumbai’s façade. He has always wanted to be a singer, and his daughter has inherited his gift and love for singing. Kapoor kidnaps the pop diva played by Aishwarya Rai Bachchan, blackmails her manager to cut an album with his daughter, and she pulls off a heart-stopping performance on a reality TV show. Talent and luck, in this case the lottery of reality television—Fanney Khan offers the same answer to social mobility as Gully Boy and Super 30. In fact, this is an answer that an earlier film on Mumbai, made by a non-Hindi film-maker, provided 10 years ago: In Slumdog Millionaire, an intelligent chaiwalla made his way to a quiz-based reality show and escaped the crime and poverty of Dharavi.

You could call these films escapist. I found them pointing to a truth many of us may be unwilling to accept—that the global economy has closed the avenues of mobility but left the illusion of them open. Hence the promise of the internet, of reality television, of messiahs who unlock our dreams.

I will end with a film that yearns for a time when the economy hadn’t taken this monstrous shape, a time of Campa Cola.

Photograph is the gentlest of this set of films: A struggling street photographer, played by Nawazuddin Siddiqui, lives in a room that he shares with several migrants in Mumbai, all of them scrounging at the edges of an economy which has no place for them. Get a factory, get a shop, Siddiqui’s grandmother tells him, find something more settled, get married. To play-act before her, Siddiqui finds a girl he had photographed, a girl whose visage is all over town because she has topped a chartered accountancy exam. The studious, wealthy girl, played by Sanya Malhotra, enjoys the charade with Siddiqui, and likes his company. He finds her the Campa that no shop in the city sells any longer. Photograph doesn’t articulate the prospects of the love story of a street photographer and a chartered accountant. It leaves us instead with memories of Campa, Polaroid photographs and Mohammed Rafi songs.

This essay was published in Mint Lounge, 27 July 2019