A Muslim family’s story in the year that led up to 6 December 1992

I was unprepared for the way Naseem, a warm amiable family story, shifts gears from sweetness to deep sadness almost imperceptibly as it builds to its moving climax set on the day the Babri Masjid was brought down in 1992. Like all of Saeed Akhtar Mirza’s films, the family is drawn affectionately, and every character in the household is shaded in nicely.

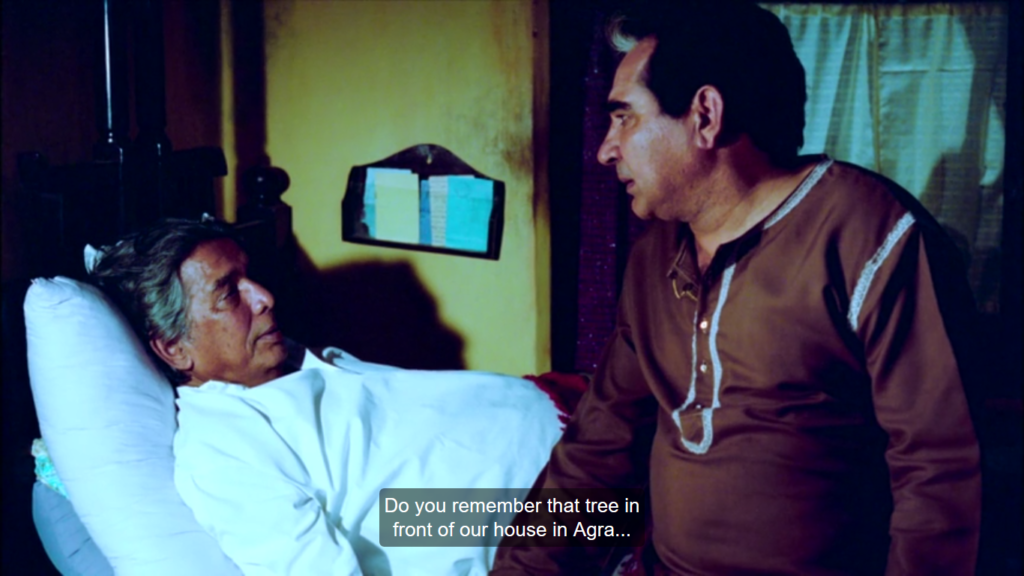

But unlike Mirza’s male-protagonist driven stories (with their interesting novelistic names), here the titular character is a teenaged girl called Naseem, and the story is centred on her relationship with her grandfather played by the poet Kaifi Azmi. Naseem is in school, and unlike most Hindi films about young girls, you actually see Naseem’s studies and classes. In her English literature class, she is studying DH Lawrence’s poem Snake, in history her class is studying the national movement, and in biology, the male and female bodies. The only other Hindi film in which we go to class with the heroine (and study with her) is Photograph, where Sanya Malhotra is a chartered accountancy topper. Think of mainstream Hindi films, on the other hand. In Hum Aapke Hain Kaun?, we learn Madhuri Dixit is studying computers, but do you ever remember her in class? Or studying? In Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, do we know what Kajol finished studying when she took off for a tour of Europe to celebrate? And yet, in the films of the 1990s, the heroine’s identity is often college student. How often do we see any interest in the cerebral or scholastic life of a woman?

There’s also the language. The entire film is spoken in conversational, thoughtfully-used Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu), but it is never affected, words used to show off an Urdu vocabulary. The word shikast, for instance, which means defeat. When I heard it, I remembered hearing it on shows on Doordarshan in the eighties and early nineties. The critic Baradwaj Rangan has spoken of the Hindi used in contemporary films–how it sounds akin to Hindi translated from writing in English. This film is the opposite of that. It gives you back some of the basic vocabulary you may have lost to English monolingualism.

The other striking thing about Naseem is an accident with a Hindu neighbour. How is it that so many stove accidents happen in Hindu kitchens, Naseem’s brother asks. “I am happy with my purdah and talaq,” his mother responds. It’s a terrific, unshowy reminder of the countless ways in which Hindu women are marginalised—foeticide, dowry abuse, widow abandonment—while the focus in Indian political discourse remains on the burkha and talaq. I was congratulating myself a couple of years ago for making this point in an argument. Naseem, which made this point in 1994, was a nice humbling moment for me.

Now streaming on the India catalogue of Mubi. Starring Mayuri Kango, Kaifi Azmi, Surekha Sikri, Kulbhushan Kharbhanda, Kay Kay Menon in a cameo