Over the past decade and a half, the Neeraj Pandey brand of thriller has given to Bollywood what Hollywood has done for the CIA: romanticising the Intelligence Bureau. Later films like War have sexed up this formula

Fifty days after the Pulwama terrorist attack, acknowledged as an intelligence failure even by the BJP-appointed governor of Jammu and Kashmir, the Hindi film Romeo Akbar Walter arrived. John Abraham plays a bank clerk, recruited by RAW to gather information in Pakistan as rumours of the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 swirl about. He leaves home and vows never to come back, and asks only that his mother be taken care of.

As its name suggests, this is the sort of film where everything has a double entendre. At the end of the film, the double meaning of mother is underlined — Abraham couldn’t perform his mother’s last rites but his motherland is in good hands. Major M.S. Grewal, the father of the film’s director Robbie Grewal, worked in military intelligence.

The trailer of India’s Most Wanted, starring Arjun Kapoor and slated for a May release, is also out. The promotional material says it is the story of the capture of ‘India’s most wanted’ terrorist without firing a single bullet. The success of the intelligence team is signposted in the promos.

Batla House, slotted for release on Independence Day, is based on the infamous encounter of 2008 when two suspected terrorists, and one ‘encounter specialist’, Inspector Mohan Chand Sharma of the Delhi Police, were killed in Delhi’s Batla House. This one too stars Abraham, who has built up quite a filmography of ‘intelligence’ films.

Earlier this year in Uri, Paresh Rawal played the role of the Modi government’s National Security Advisor, Ajit Doval. Rawal’s character is called Govind Bhardwaj, and he sports a moustache similar to Doval’s. He uses information from RAW, ISRO and DRDO to strategise a ‘surgical strike’. Doval, an intelligence man himself, served as director of the Intelligence Bureau, the country’s internal spying department, set up by the British in the 1880s (RAW came into being in the 1960s, in the aftermath of the Sino-Indian war, and is responsible for foreign espionage).

There is a clear message in these movies: that there are, deep within the government, officers working ceaselessly to keep you safe. The men of the government are mostly shown as slow and dull, with splendid inertia and annoying questions, while the men of action save the day.

Like everyone else here, I hate government offices. It is insufferable to be told that there are some officers who work hard when you still have to submit documents in quintuplicate at government offices and never encounter these industrious officers yourself. More importantly, it feeds a disingenuous narrative — the idea that things are ‘under control’ and that the state knows everything there is to know, the ‘surgical strike’ narrative of omniscience.

It is easy to imagine that this on-screen romance with the intelligence community is timed with an important election year, particularly for a right-wing government pumped up on national security concerns. But the Mumbai film industry’s crush on the intelligence forces goes further back, at least to 2012, when Kahaani and Ek Tha Tiger were massive hits.

Hollywood’s long-standing love affair with the CIA is well known. Films like Zero Dark Thirty and Argo, and TV series like Homeland and 24 rolled out after 9/11. But the association goes even further back, to the years following World War II, when there were Nazi-hunting espionage thrillers like Notorious, Where Eagles Dare and Marathon Man. The 90s (and the end of the Cold War) spawned films based on Tom Clancy novels — The Hunt for Red October, Patriot Games, Clear and Present Danger. In all these films, American intelligence is heroic and correct: Zero Dark Thirty justifies the torture of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay because it leads to the capture of Osama bin Laden. The PR exercise that Hollywood performs for the CIA is well documented in books such as Spooked: How the CIA Manipulates the Media and Hoodwinks Hollywood, which notes that the CIA invited Tom Clancy to meet them. Actor Ben Affleck who played the Clancy character Jack Ryan was also invited by the CIA, and the result of these meetings was Argo.

RAW and other Indian intelligence agencies had a budget of ₹60,000 crore in 2018. As lawyer Prashant Bhushan argued in a PIL before the Supreme Court, this is roughly ₹5,000 crore more than India’s health budget for that year. The PIL asked for an audit of how the intelligence forces spent this money, but the SC dismissed it saying national security would be compromised. Do RAW and IB pay Bollywood for PR? We don’t know because we can’t ask.

In 2012, two films featuring intelligence operatives were superbly successful. In the opening minutes of Ek Tha Tiger, Salman Khan, a RAW officer, tosses a wad of cash in the air in a sticky situation and his stocky frame swaggers away like a crab in slow-motion. And when Khan elopes with an ISI spy played by Katrina Kaif, his genial RAW boss, played by the marvellous Girish Karnad, chooses to keep quiet — because Khan possesses much knowledge but will never betray his country.

More remarkable is Kahaani, which was made on a budget of ₹8 crore and earned over ₹112 crore. A heavily pregnant Vidya Balan turns out to be an elite operative who brings down a terrorist who had carried out a deadly gas attack on the Kolkata metro rail. She is part of such an exclusive unit that even the surly fox played by Nawazuddin Siddiqui is not aware of it. Interestingly, while in Kahaani, Indian intelligence comes away looking ill-tempered, it is also the real star of the movie — with the power and discretion to create crack teams with able agents like Balan.

Last year, in Raazi, which earned ₹195 crore, Alia Bhatt played Sehmat, a Kashmiri spy’s daughter emotionally blackmailed into spying for the government by her dying father. Sehmat’s devotion to duty appears to come from blackmail and fear, not from ideology and conviction. Intentional or not, I thought this was an unusually honest picture — after all, spies work under unforgiving pressure where the fear of death or jail-time is ever present. Raazi is based on the book Sehmat Calling by ex-Navy serviceman Harinder S. Sikka.

Last year, there was also Parmanu, propaganda for the BJP and another box-office success. Here, John Abraham is a civil servant working for the ‘research and strategy’ department, who successfully leads India to her second nuclear test in Pokhran in 1998, right under the nose of the CIA.

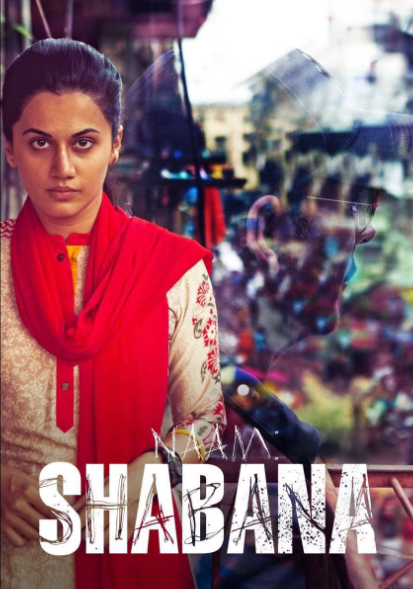

In 2017, in Naam Shabana, a young woman murders her alcoholic, abusive father and is sent to a juvenile home. She is later recruited by the intelligence forces when her boyfriend is murdered by a gang of rich brats. Taapsee Pannu plays Shabana Khan. Her recruiter first helps her avenge her boyfriend’s murder. When this satisfying job is done, she is trained for an elite mission abroad to nab a face-shifting terrorist. I love the premise of this story — intelligence forces buy complete loyalty from recruits by helping fulfil their need for justice, the scarcest commodity in the Indian system.

Naam Shabana spins off into Baby (2015), where a crack intelligence team led by Akshay Kumar brings home a terrorist nestled in the ‘Middle-East’, which in contemporary Hindi film topography is the terrain of oil wealth-fuelled terrorism, paedophilia and all manners of human rights violations.

The highest-earning Hindi film in 2017, which made more than ₹500 crore (officially) is Tiger Zinda Hai, where the ex-RAW agent played by Salman Khan and the former ISI spy played by Katrina Kaif rescue 25 Indian nurses and 15 Pakistani nurses held by an ISIS-like group in Iraq, while the CIA twiddles its thumbs. Khan and Kaif go into hiding after the rescue because they suspect that their respective governments will not abide such bilateral co-operation. Governments are tied up in petty rivalries, the film notes, but intelligence agencies are above all this.

In Phantom (2015), disgraced ex-army man Saif Ali Khan and RAW agent Katrina Kaif execute the Indian fantasy of travelling to Pakistan and taking out all the planners responsible for the 26/11 attacks. In Bang Bang (2014), Indian intelligence works with British MI6 to nab an international terrorist; the British leave much of the heavy lifting to the agent played by Hrithik Roshan. Two years earlier, in D-Day, a ‘crack team’ led by Arjun Rampal’s character screened the fantasy of getting Dawood alive in Pakistan, with the tagline India Strikes Back.

Much like Hollywood, Bollywood too never addresses India’s intelligence fiascos — the terror strikes of 26/11, the Kargil intrusion of 1999, the assassination of prime ministers . In the film Madras Cafe, the RAW officer played by John Abraham even warns the former Indian Prime Minister against going to a rally where he will be assassinated, but he doesn’t heed the advice.

There is also admiration for disturbing behaviour. Why should the Indian state be observing a young Indian Muslim woman as it did in Naam Shabana? Isn’t it illegal? Is it meant to rationalise the Gujarat government’s surveillance of a young female architect?

Only one film in recent years has laid bare the rot in the inner workings of our security forces. In Jolly LLB 2, an amoral newbie lawyer finds his conscience when he comes across the case of a young Muslim man killed in cold blood by the police. This is termed an encounter death, a constable is killed to make the encounter more plausible, and an ‘encounter specialist’ cop earns yet another mark in a celebrated career. That this film stars ‘nationalist’ hero Akshay Kumar, and is a bona fide box-office hit is the sort of nice surprise that Hindi cinema offers far too seldom.

Originally published in The Hindu’s Sunday magazine: https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/movies/bollywoods-love-affair-with-the-intelligence-forces/article26954475.ece