The courtesan, a long-time fascination of Hindi cinema, is being replaced by the sportsperson. Corporeal labour and the art of sports is the kind of performance that the politics of post-2000 India celebrates. The courtesan represents women in pre-modern India, the sportsperson represents the ideal citizen of contemporary India. In particular, the sportswoman

In the book Dancing with the Nation, the gender and sexuality studies scholar Ruth Vanita studied 235 films in “Bombay cinema” where the courtesan is a “relevant” character. This is not an exhaustive list, she noted, but the largest sample studied so far. It underlined just how central the figure of the courtesan is to popular Hindi cinema.The term courtesan used in this analysis means not only the ‘tawaif’ in the ‘kotha’ but any woman performer, including singers, dancers, folks artists like nautanki performers and actors. Later in the essay,I discuss the nomenclature. Hollywood also makes the occasional film on women performers—such as Judy (2019), Black Swan (2010), Chicago (2002) but is nowhere near as fixated as Hindi cinema is on the performing woman. “Every major female star from the 1950s to the 1990s played a courtesan at least once in her career,” Vanita has written in Dancing with the Nation.

Every major Hindi film heroine of this generation, however, will likely play a sportsperson. And indeed, every major hero too. The courtesan (in all her avatars) is now an increasingly anachronistic figure although she may yet feature in period pieces by filmmaker Sanjay Leela Bhansali (who appears to have a fascination for the performing woman—Khamoshi, Bajirao Mastani, Devdas, Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam too?). The performing body and person that is in focus at this moment is that of the sportsperson, and in particular the sportswoman–a shift that suggests women earn a public citizenship akin to the male citizen when they play sport. By performing for the nation, by embodying their duty to the nation, sports endows women with a higher degree of citizenship than was previously available to them. I expand on this later.

The sportsperson appears first in a major way in 2001 with Lagaan, the first Hindi film since 1958 (Mother India) to make the final shortlist of nominations for the Oscars. (Incidentally, this is a film where the leading woman is a part of the cricket team at first but dropped as soon as the team gathers momentum.) The film’s double success of smashing box office returns and the Oscar coup inaugurated Bollywood’s interest in the sport film. In the two decades since, the sport film has emerged as a full-fledged Bollywood genre with distinctive features. Every major star in Mumbai, men and women, has done a sport film since Lagaan and several more are in the works after the 2021 Olympics campaign, the best ever for India in terms of medals won.

A brief list: Aamir Khan, who pioneered the genre in Bollywood, has done Lagaan about a Gujarati cricket team playing a British colonial team and Dangal (2016), the story of a patriarch coaching his girls in wrestling. Both are massive hits. In 2005, a film called Iqbal about a deaf-mute fast bowler played by the then newcomer Shreyas Talpade became a major success and made Talpade a leading man contender for a few years. Shah Rukh Khan leads Chak de India (2007), playing a (disgraced former player) and coach for the Indian women’s hockey team, an influential hit whose dialogues and songs remain in regular circulation 14 years after its release. Salman Khan and Anushka Sharma are both wrestlers in Sultan (2016). Priyanka Chopra plays Mary Kom (2014), the real-life six-time women’s boxing world champion in the eponymous biopic. Sushant Singh Rajput plays India’s former cricket captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni in MS Dhoni (2017), the late actor’s biggest career success. Akshay Kumar plays the manager of the independent India’s first Olympic men’s hockey team in Gold (2018), which did reasonably at the box office. Kangana Ranaut plays a state-level athlete in Tanu Weds Manu Returns (2015), her biggest hit, and a retired kabaddi player in Panga (2020), a box-office failure for which Ranaut nevertheless won a National award. Parineeti Chopra plays the badminton champion Saina Nehwal in Saina (2021), and Taapsee Pannu and Bhumi Pednekar play champion shooters in Saand kii Aankh (2019). Rannveer Singh is Kapil Dev in 83, the story of the Indian cricket team’s world cup win. Rashmi Rocket (2021) and Shabash Mitthu (forthcoming) both star Taapsee Pannu; in the first, she plays a sprinter, and in the second captain of the Indian women’s cricket team Mithali Raj.

This is not an exhaustive list. Biopics on the double Olympic medallist in badminton PV Sindhu and India’s first individual Olympic medallist weightlighter Karnam Malleswari are in the works. I have left out several notable films because my intention is not encyclopaedic but to make an argument.

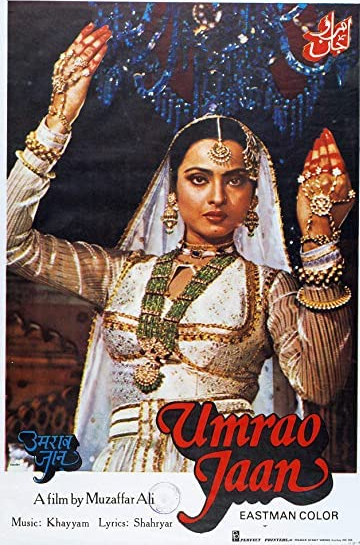

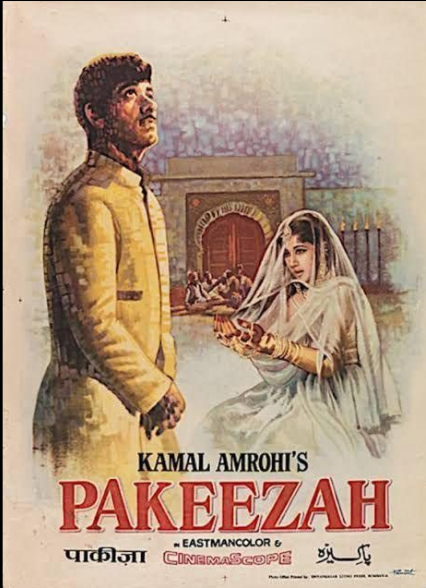

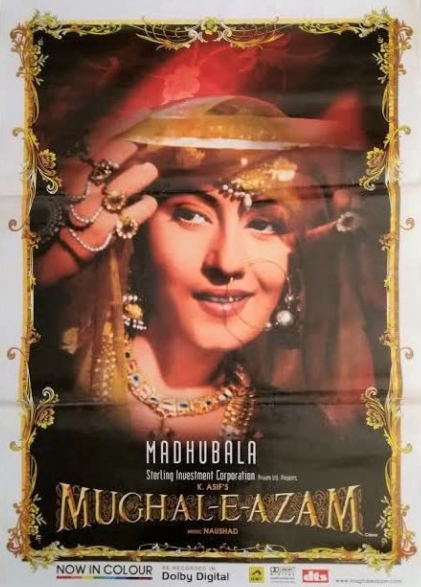

For long, perhaps forever, the Hindi film’s idea of the performer is the singer/dancer in the mould of the courtesan, often identified with the Islamicate film due to the outsize box office returns and the influence of certain films such as Umrao Jaan, Pakeezah, Mughal-e-Azam. But as Vanita noted, there are several notable Hindu devadasi or proscenium style dancer characters: Waheeda Rahman’s Rosie who dances a bharatnatyam-style form in Guide, Rekha’s Vasantasena in Utsav, Vyajayanthimala Bali’s Chandramukhi in Devdas, or indeed any iteration of Chandramukhi in the various versions of Devdas.

Variations of the courtesan are the dancing girl (most famously essayed by Helen) and the item girl from the late 1990s through the Noughties, begun by well-known actress dancers like Urmila Matondkar in China Gate (‘Chhamma Chhamma’) and Shilpa Shetty in the film Shool (‘Dilwalon ke dil kaa karaar loot ke’). But the figure has also been played as itinerant gypsy performer like Aruna Irani in Carvaan, Hema Malini in Seeta aur Geeta and Jaya Bhaduri Bachchan in Zanjeer. Tabu has played a version of this figure as bar dancer in Chandni Bar, Madhuri Dixit as a hybrid of the bar dancer and show performer in Tezaab, and Kareena Kapoor as a hybrid of a street walker and bar dancer in Chameli and Talaash. Perhaps, most interesting of these renditions is Smita Patil as an actress in Bhumika, the daughter of a family where her grandmother is a well-known singer with her own gramophone records. Another favourite is Urmila Matondkar’s Millie in the marvellous Rangeela, where she plays a background film set dancer who catches the director’s eye and plays the leading lady, an acknowledgement of the careers of several marquee actors in Hindi film like Sadhona Bose, Vyjayanthimala, Waheeda Rehman, Hema Malini who were known as accomplished dancers and were primarily chosen for their dancing skills.

Usha Iyer’s book Dancing Women is an account of how such dancing stars shaped Hindi cinema, and indeed changed the technologies of its idiom. (For the film Guide, for instance, the crew had to devise a certain new camera placement and angle in order to capture its leading actress Waheeda Rahman’s dance movement. In several films where well-known dancers were cast, filmmakers would insert special song and dance sequences to showcase their dancing.)

Why is the courtesan so central to the idea of the performing figure? One reason is the nature of film financing, a considerable part of which came from cotton mill owners in the Bombay Presidency, according to film scholar Debashree Mukherjee in the book Bombay Hustle. “One of Bombay’s oldest film studios Kohinoor Film Company was started by a local cotton mill owner Dwarkadas Sampat…The earliest avatar of Bombay Talkies, the “Indian Players” received financial backing from the cotton merchant-turned Theosophist Jamnadas Dwarkadas in 1923 for its proposed film, Light of Asia…When the Indian Players started Bombay Talkies, their studio was built on the property of F. E. Dinshaw, a member of the BT Board of Directors who had made his fortunes partly from the Bombay cotton industry,” Mukherjee writes.

In Dancing with the Nation, Vanita makes clear that many of these business magnates were also patrons of the courtesan economy and the performing arts culture in general, alongside aristocratic patrons. who started to dwindle in the 20th century. They brought the aesthetic of the courtesan culture as well as poets and writers along with the performing women. A significant number of women from courtesan lineages did indeed come into public performance on stage, radio, theatre and film in the early 20th century. These include Begum Akhtar and MS Subbalakshmi and Jaddan Bai, who set up her own film company. Many male musicians and performers associated with courts worked on stage and film, such as Pt Lachhu Maharaj, an exponent of Kathak, who choreographed Mughal-e-Azam and Pakeezah among many others. His descendant Birju Maharaj, a famous stage dancer, worked on Devdas (2002) and Desh Ishqiya. Poets who wrote and performed for courtesan salons have also written for film as lyricists and other film writing. The film industry derived a lot from the courtesan ecology, Vanita noted, both personnel and patronage, and hence, ideas and muses too.

Why do I say the sportsperson is the new performing figure,who has replaced the courtesan? Consider the similarities. First, both sport and courtesan cultures are corporeal; they require bodily labour. Second, they are both public, the work is displayed. The verb ‘perform’ is utilised both for playing sport and any musical or rhythm-based labour, including dance. These two elements, corporeality and public-ness, blur the distinction between dance and sport. Many forms of martial art such as capoeira (Brazil) and the kalaripayattu (India, Kerala) combine elements of dance; in fact kalaripayattu performances are held on stage in Kerala. The nomenclature itself is an indication: the art in a martial activity underlines the choreographic element. Note also the nature of skating and gymnastics (as well as gymnastics-like traditional forms such as malkhamb in India); both are summer Olympic sport event but are they not like dance performances too? An aside: the film Zubeida (2001) has a cheeky sequence in this regard. The film is the story of an actor in early Hindi cinema, played by the star Karisma Kapoor. The dance master for a film sequence she is performing in exclaims that the choreography in Bombay cinema is no longer graceful, but like PT (the term typically used for physical exercise classes in Indian schools).

Third, both sport and courtesan culture involves a guardian-like authority figure—the coach in sport and the nayika/madam in courtesanship. Fourth, both sportsperson and courtesan are identities that are utilised to tell a story about nationalism and citizenship. Finally, sport and courtesanship are both sustained by patronage and the Hindi film underlines this relationship.

The corporeal and choreographic nature of sportoffer rich aesthetics for the movie camera, much like dance.The moving camera savours dance, as is evident from the lavish sets laid out for dance sequences such as Pyaar kiya toh darna kya in Mughal-e-Azam, the stage numbers in Guide, the mujras in Umrao Jaan and the dance sequences in Sanjay Leela Bhansali films to name only the most spectacular. In the sport film, the physical training montage has emerged as a staple sequence showcasing the sculpted body of the athlete. Often, this sequence is set to a song, underlining the dance metaphor. It was Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013) that likely began the montage focussed on the individual body, but the training sequence was present in Lagaan itself (Chale Chalo) and the necessity for a beautiful body was evident in Aamir Khan baring his (noticeably-slimmer) torso through the film. In Mary Kom (2014), we see the individual sportswoman in focus for the first time. Interestingly, the film’s producer is Sanjay Leela Bhansali, a filmmaker known for spectacular choreography and a continued commitment to the song and dance form, increasingly unusual in Bollywood. Many characters in his films are courtesan, courtesan-like or simply performers.

Then, the mentor-like figure. The nayika (madam) or the head of the kotha/brothel in the courtesan film is the coach in the sport film. This presence does two things. One, it establishes that the nature of courtesan-ship and sportsmanship is a way of life rather than simply a profession, a guru showing the path. And second, it enables big stars who may not be physically fit enough for the central role to be a part of the project. For instance, Amitabh Bachchan stars as the coach of a slum football team in the anticipated film Jhund, and Ajay Devgn as real-life Indian football coach Syed Abdul Rahman in whose time the Indian football team reached the semi-finals of the 1956 Olympics. Most famously, Aamir Khan and Shah Rukh Khan both played coaches in Dangal and Chak De India, each the protagonist of the film, reflecting perhaps how crucial it is to have a male star in a mainstream film about women.

Both sport and courtesan cultures are corporeal; they require bodily labour. Second, they are both public, the work is displayed. The verb ‘perform’ is utilised both for playing sport and any musical or rhythm-based labour, including dance. These two elements, corporeality and public-ness, blur the distinction between dance and sport. Many forms of martial art such as capoeira (Brazil) and the kalaripayattu (India, Kerala) combine elements of dance; in fact kalaripayattu performances are held on stage in Kerala. The nomenclature itself is an indication: the art in a martial activity underlines the choreographic element. Note also the nature of skating and gymnastics (as well as gymnastics-like traditional forms such as malkhamb in India); both are summer Olympic sport event but are they not like dance performances too?

Both the courtesan and the sportsperson are figures used to make an argument about citizenship and nationalism. For several decades after the Bombay film industry began, the performing woman was the only category of subcontinental woman with financial independence and a public presence. Doctors, lawyers and other figures of modernity did exist but were the exception. The performing woman facilitates both the projection of a woman character as well as the opportunity to tell a particular story about the new Indian nation—the courtesan or nautanki artist or performer marks tradition in India, writes Vanita. Filmmakers are often empathic to the courtesan figure. Sometimes, their stories are presented as empowering. Yet, Vanita rightly noted that the courtesan’s trope is ultimately a cautionary tale used to tell the audience that a woman who has sex for pleasure and a public life does not come to a happy end. In contrast to the courtesan is the figure of the ‘bhadramahila’, Iyer has posited in Dancing Women .

The bhadramahila or new Indian woman is an important construction of the National Movement, the scholar Partha Chatterjee wrote in the influential essay ‘Colonialism, Nationalism and the Colonialised Woman’. She must preserve the values of Indian tradition while benefitting from modern education and values in such a way that Indian men could flourish in the modern world shaped by Western values. This idealised figure of Indian femininity was essential to preserve and mark the new Indian identity superior to the Western identity.

This distinction becomes clearer with an understanding of how women lobbied for the vote in the national movement. In Citizenship and its Discontents, political scientist Niraja Gopal Jayal writes that Congress leaders in the national movement, including women such as Sarojini Naidu, held the “curiously” bifurcated notion of separate spheres for men and women. The private sphere of the home was seen as the domain of responsibilities towards children and families—by implication that of women—and the public sphere as the domain for the exercise of rights, which was that of men. Extending the vote to women was premised on the understanding (presumably common to both men and women) that they would bring the values of the private sphere—of care, responsibility and domesticity, mothering and supporting good citizens—to the public sphere “without in any way threatening men’s exercise of their rights and civic duties” (emphasis mine). Note the words, “without in any way threatening” the patriarchal order. To me, this means women are expected to be supporting actors in the public sphere, not lead actors articulating their own demands.

It reminds me ineffably of the episode in the Ramayana. When Ram was in exile, every day the brothers Ram and Laxman would set out in the forest. Laxman had drawn a circle around the dwelling and asked Sita not to step outside the ring. This was the Laxman rekha. One day when Sita saw a beautiful deer, she stepped outside the rekha and was abducted by the demon king Ravana’s squad. When a woman crosses the line, two kingdoms may go to war, this suggests.

Women’s citizenship in the Indian nation seems to be premised on the Lakshman rekha. When they remain in the sphere of domesticity and domestic activities, their citizenship is legitimate and inviolable. The moment they cross the line into men’s activities, they are vulnerable to be violated. Every time there is an assault on a woman in a public space, this distinction between spheres becomes clear. It is spelt out in what I call the three inevitable questions: What was she doing there? What was she wearing? Where was she going? Explicit in these questions in the belief that women should remain within the private sphere of the home and that when they step outside the Lakshman rekha, they are open to be violated.

The sportsperson is the embodiment of the ideal citizen—patriotic, hard-working and disciplined. This citizen can be man or woman. Often, the sportsperson is of minority identity, a Muslim or a tribal citizen, and sports achievement is the test of their good citizenship. Moments of sporting triumph in these films are unambiguously marked with the tricolour fluttering, the national anthem playing and various other national motifs, which reinforce the nationalism of minority identities in particular.

This brings me to the last point about patronage. The courtesan performs for her clients whose payment sustains the kotha. This dynamic is clearly established by the register of her performances catering to their gazes, as well as developments in the plot which reveal that clients hold power over her. This client patronage is largely projected as problematic, a sign of her dependence and her licentiousness.

For the sportsperson, the patron is the nation-state, symbolised by the tricolour and other national motifs . It is an unambiguously pure, moral and venerable relationship—the good citizen and the land that nurtures them. There is no exploitation, no power play here, only love, commitment and the good modern value of nationalism, calling for discipline, fraternityand loyalty among citizens. The nation state offers patronage to both men and women citizens, in return for discipline, loyalty and aspiration. The courtesan’s story is a cautionary tale, the athlete’s story is one of triumph.

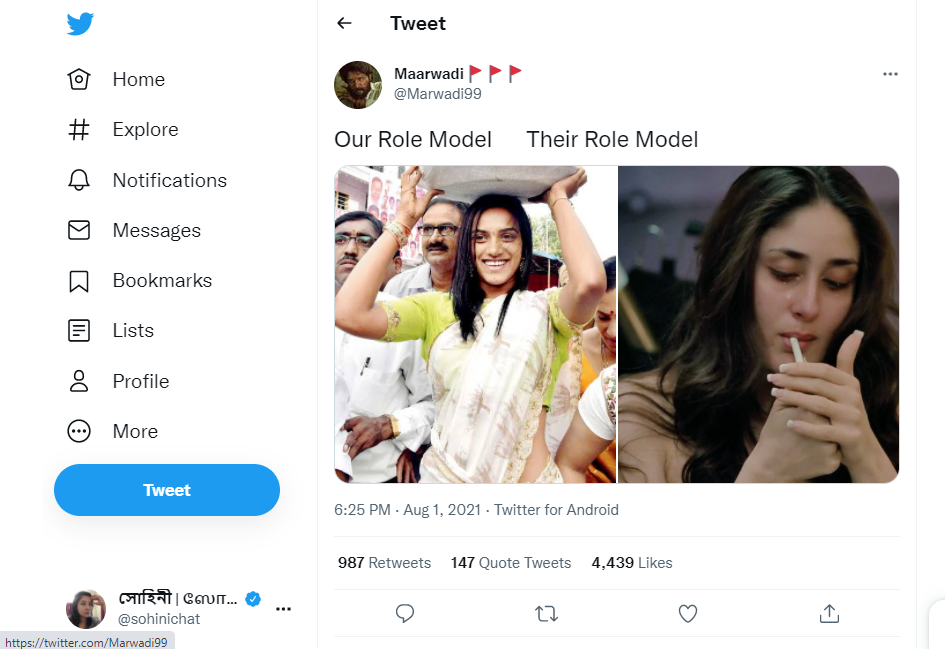

I’ll end this essay with a meme that was doing the rounds on social media during India’s 2021 campaign at the Tokyo Olympics where India won 7 medals, the highest in her history and came close to podium finishes in several events. This meme comprised two images, one of the double Olympic medallist in badminton PV Sindhu carrying a pan on her head and the other of the film star Kareena Kapoor Khan lighting a cigarette. Above Sindhu’s image were the words, “Our role model” and above Kapoor Khan’s, the words, “Their role model”.

It was that distinction between the immoral performing woman (the courtesan figure) and the good woman citizen again, the one articulated in the National Movement. But now, the bhadramahila has been reimagined in a more public role. She is still good, disciplined, educated but she has made her presence outside the home in the public eye. She is now the athlete heroine.

Published in Seminar magazine, May 2022 edition