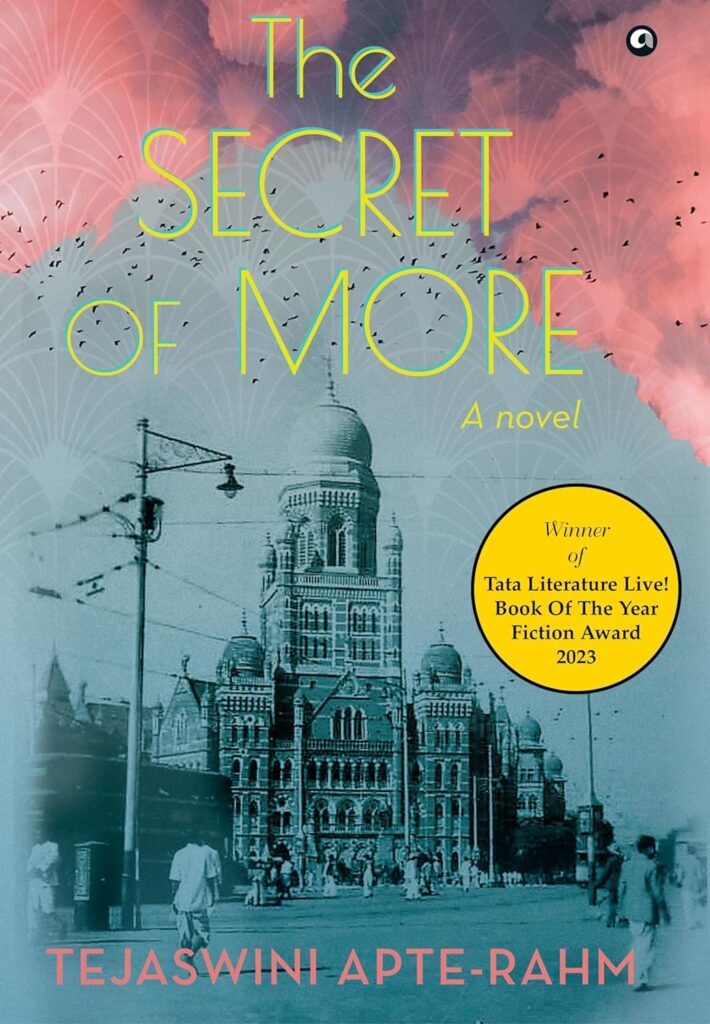

Tejaswini Apte-Rahm’s novel The Secret of More is set in the Bombay of the early 20th century, when the motion picture industry was being born and the seismic political changes that shaped the age of democracy and nationalism were underway

When Tejaswini Apte Rahm’s novel The Secret of More won the best book of the year (fiction) at the 2023 Tata Litlive fest, she thanked her father Arvind Apte for introducing her to “this world of historical discovery”. Interestingly, it was 11 months since her book had been published but the first time I heard of it was the night it took home a prestigious prize, winning over two very worthy contenders. Her great grandfather was one of Dadasaheb Phalke’s financiers, the man who is credited with making India’s first feature film, Raja Harishchandra.

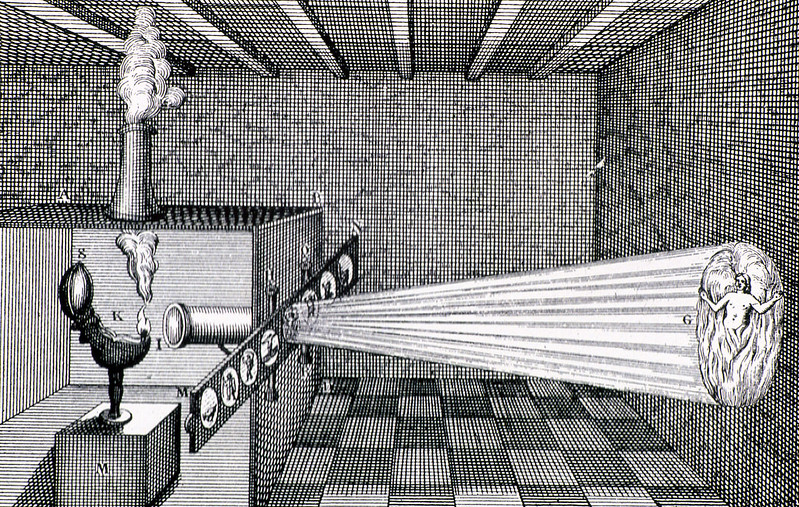

The world of early Bombay cinema has been of increasing interest to me over the past half a decade. I was taught, briefly, by arguably the greatest scholar of Bombay cinema, Prof Rosie Thomas, whose outstanding book Bombay Before Bollywood introduced me to the fascinating world of B and C-grade films in Bombay filmmaking in the 1940s and ‘50s—the Fearless Nadia stunt films, and the Arabian Nights-based magic films. Phalke’s films, however, were in the decade of the 1910s. Both the stunt and magic genres involve trick photography. In the early years of film technology, filmmakers had a lot of fun playing with the technology of moving pictures. And this was, in fact, a feature of mythological films as well—think of the stories in our epics and consider the potential of the then new technology of moving images to essay Hanuman’s feat of flying with a mountain on one hand, for instance. The Encyclopaedia Brittanica entry on Phalke mentions his penchant for special effects.

Naturally, I had to read this novel. The arc of the story is simple, the quintessential Bombay story of making it in the city of dreams: a young man, Tatya, arrives in Bombay, learns the ropes of selling textiles, makes a fortune in the industry during WWI, is seduced by the cinema and makes films for a decade or so, unsettling the rhythm of his cheerful, prosperous household although there is no adultery in the physical sense. Within Tatya’s life story are the stories of four women in the main—his widowed mother-in-law Mai, his wife Radha, his daughter Durga and the woman he unexpectedly falls in love with, Kamal bai.

Apte Rahm does a superb job of detailing the evolution of the new technology from the picture shows using painted glass slides projected with the magic lantern to show movement, to early cinema using the cinematograph, developed originally by the Lumiere Brothers, which could photograph and project images at the rate of 16 frames per second. In other words, capture genuine movement, not only offer the impression of movement. The turn of the 20th century was a heady time for the development of camera technologies with several inventors, and Apte-Rahm is serious about her historical detailing, with more than one figure who is a filmmaking pioneer. It would be easy to deify one individual over others, and fiction has the license to do this, but it is more intricate, more interesting to see the romance of technology in those early decades of the 20th century.

In a line, the novel is superb in its detailing of technology development and its relationship (and flings and fatal attractions) with human society.

What I did not expect at all is the magnificent rendering of the lives and limitations of three generations of women—the taciturn widow Mai, the mostly-contented Radha, the effervescent Durga and the alluring and courageous actor Kamalbai. Through Mai, we learn of the multitude of fasts that women practised to keep a husband, exhausting themselves to illness. She is not simply a fanatic for rituals, she knows the privations of widowhood first hand. We learn the secret of how to polish German silver and the recipes of traditional Marathi cuisine through the routines of Radha’s married life. We see how she is made to feel embarrassed for her reading habit, because it was not becoming of a good wife to do the things men did. What if she read the novels that puts ideas of romance in their silly heads? We understand the madness of what she did to avoid widowhood at any cost. We watch the little tricks and games of early Bombay cinema with Kamal, and marvel at the fortitude it took for a career in the public eye in the 1910s. We feel the exhilaration of the world that opens up to Durga in the 1940s with education, and her suffocation at the premature closure of her studies, because an educated woman would not find a husband.

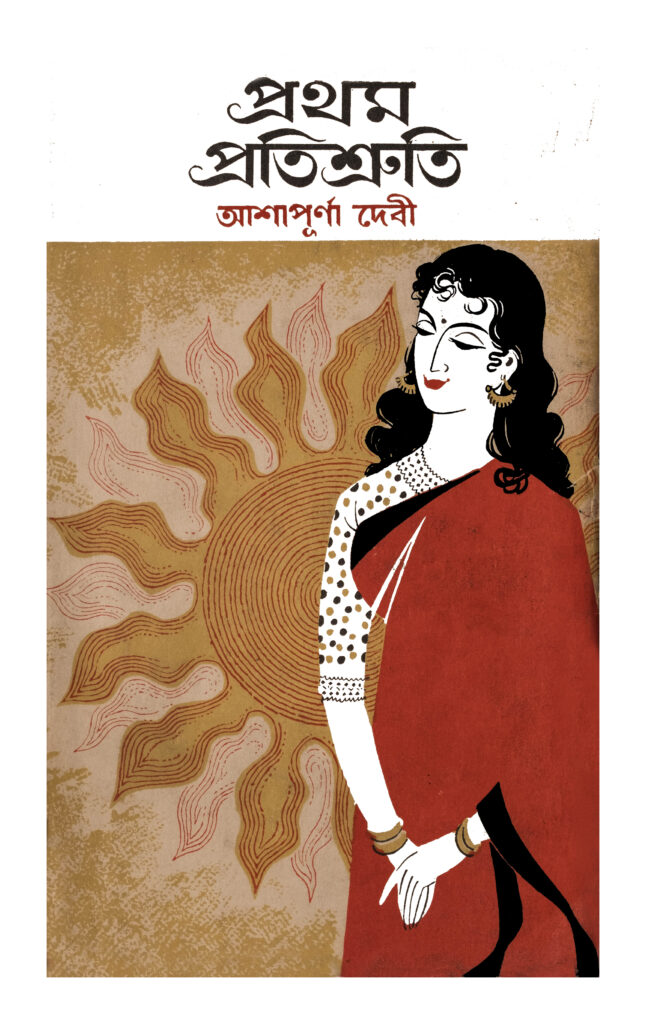

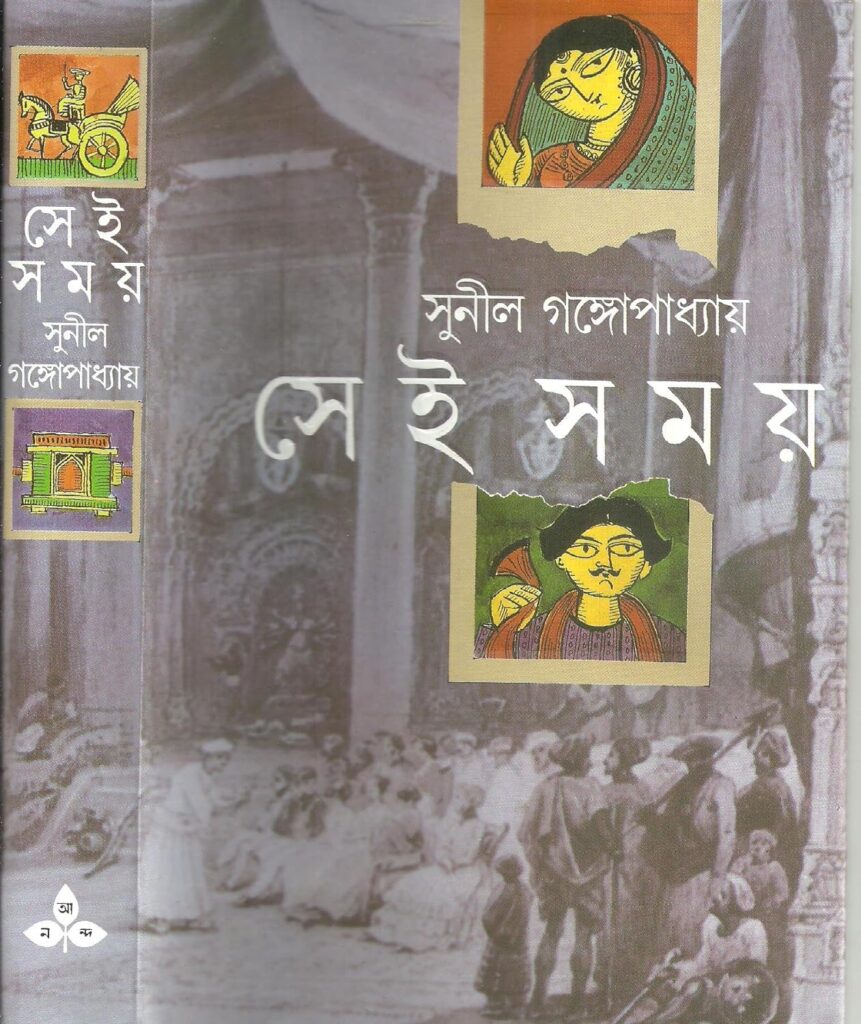

In its portrait of domesticity and how stifling the lives of women could be before they could access some of the licenses that modernity offers, The Secret of More is an equal to Ashapurna Debi’s magnificent bildungsroman Prothom Protisruti (The First Promise) and Sunil Ganguly’s magisterial trilogy on the (so-called) Bengal Renaissance, particularly Shei Samay (Those Days) and Prothom Alo (First Light in the English translation). I had not thought that a writer today could equal the portrayal of what it was like to be a woman in late colonial India, at the threshold of tradition and modernity, the home and the world. Mainly because of age. Ashapurna Debi was born in 1909, according to her Wikipedia entry, and Prothom Protisruti published in 1964. Sunil Ganguly was born in the early 1930s (Wikipedia), and published in the early 1980s. Debi would certainly have some lived experience of those decades, Ganguly too although lesser than Debi’s.

Apte-Rahm’s world-building of Bombay in the first four decades of the twentieth century, arguably one of the great cities of this century, is ridiculously good–both in the relatively public (and technological) sphere of the film industry, and the private sphere of domesticity and the lives of women. This richness of detail gave me a sense of the magnitude of events in the long twentieth century, and how far we have come—men and women, technology and the desires (and fortitude) of the human heart.