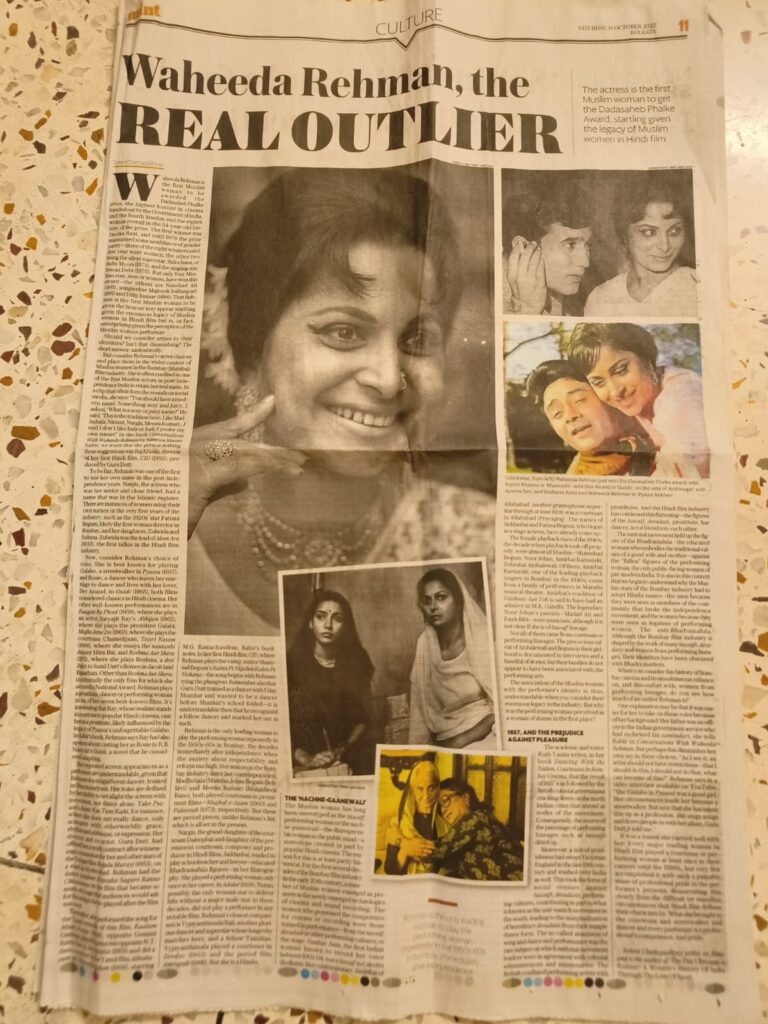

The actor is the first Muslim woman to get the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, startling given the legacy of Muslim women in Hindi film

Waheeda Rehman is the first Muslim woman to be awarded the Dadasaheb Phalke prize, the highest honour in cinema handed out by the Government of India, and the fourth Muslim and the eighth woman overall in the 54-year-old history of the prize.

The first winner was Devika Rani, and until 1976 the prize maintained some semblance of gender parity—three of the eight winners until that year were women, the other two being the silent era superstar, Sulochana or Ruby Myers (1973), and the singing star, Kanan Debi (1976). But only four Muslims ever, men or women, have won this award—the others are composer Naushad Ali (1981), songwriter Majrooh Sultanpuri (1991) and actor Dilip Kumar (1994).

That Rehman is the first Muslim woman to be given the honour may appear startling given the enormous legacy of Muslim women in Hindi film but is, in fact, unsurprising given the perception of the Muslim woman performer.

But first, should we consider artists by their identities? Isn’t it diminishing? The short answer: undoubtedly.

Consider Rehman’s career choices, however, and place them in the wider context of Muslim women in the Bombay (Mumbai) film industry. She is often credited as one of the first Muslim actors in post-independence India to retain her real name. In a clip that often does the rounds on social media, she says: “You should have a modern name. Something sexy and juicy. I asked, ‘What is a sexy or juicy name?’ He said, ‘This is the tradition here. Like Madhubala, Nimmi, Nargis, Meena Kumari…I said I don’t like bala or bali. I prefer my own name!” In the book Conversations With Waheeda Rehman by Nasreen Munni Kabir, we learn that the person making these suggestions was Raj Khosla, director of her first Hindi film, CID (1955), produced by Guru Dutt.

To be fair, Rehman was one of the first to use her own name in the post-independence years. Nargis, the actress who was her senior and close friend, had a name that was in the Islamic register. There are instances of women using their own names in the very first years of the industry, such as the 1920s’ star Fatima Begum, likely the first woman director in Bombay, and her daughters, Zubeida and Sultana. Zubeida was the lead of Alam Ara (1933), the first talkie in the Hindi film industry.

Now, consider Rehman’s choice of roles. She is best known for playing Gulabo, a streetwalker in Pyaasa (1957), and Rosie, a dancer who leaves her marriage to dance and lives with her lover, Dev Anand, in Guide (1965), both films considered classics in Hindi cinema. Her other well-known performances are in Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), where she plays an actor, Satyajit Ray’s Abhijan (1962), where she plays the prostitute Gulabi, Mujhe Jeene Do (1963), where she plays the courtesan Chamelijaan, Teesri Kasam (1966), where she essays the nautanki dancer Hira Bai, and Reshma Aur Shera (1971), where she plays Reshma, a desi Juliet to Sunil Dutt’s Romeo in dacoit land Rajasthan.

Other than Reshma Aur Shera, incidentally the only film for which she secured a National Award, Rehman plays a prostitute, dancer or performing woman in six of her seven best-known films. It’s interesting that Ray, whose realism stands in contrast to popular Hindi cinema, cast her as a prostitute, likely influenced by the legacy of Pyaasa’s unforgettable Gulabo. In Kabir’s book, Rehman says Ray had also spoken about casting her as Rosie in RK Narayan’s Guide, a novel that he considered adapting.

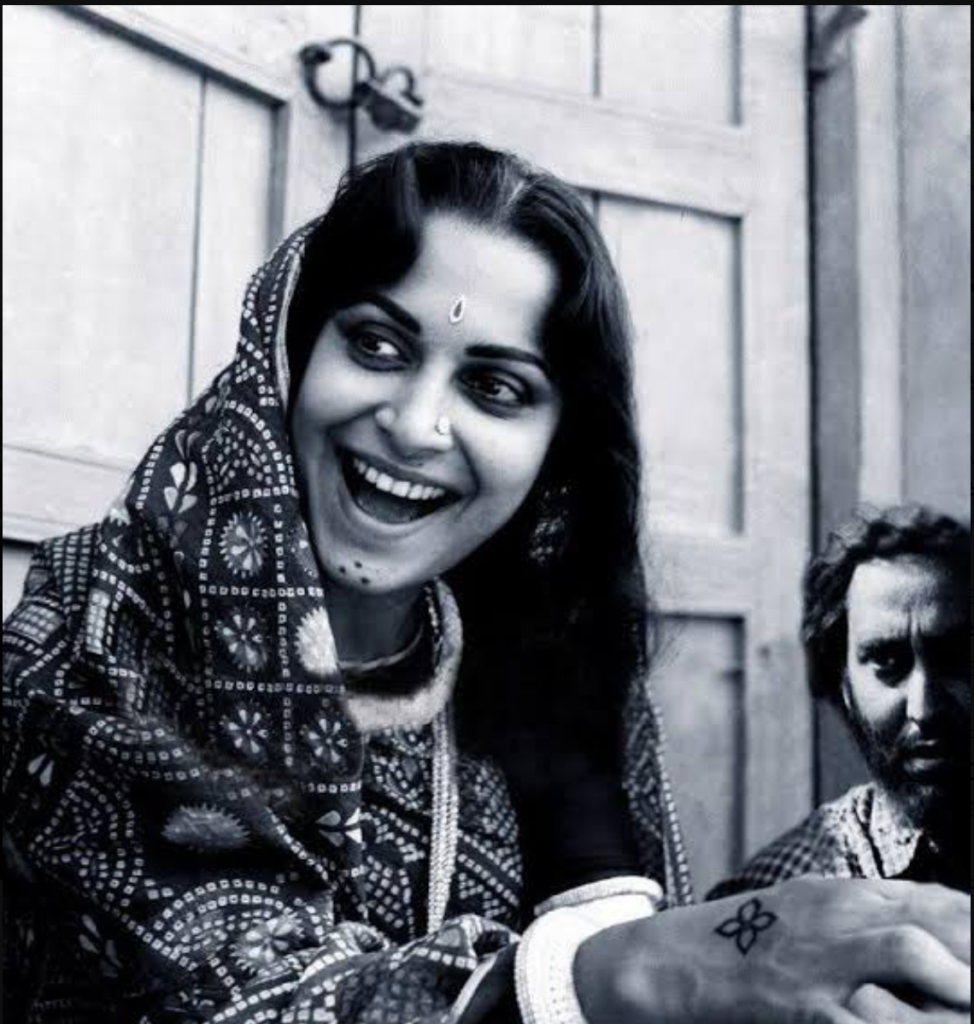

Her repeated screen appearances as a performer are understandable, given that Rehman is a magnificent dancer, trained in Bharatanatyam. Her roles are defined by her ability to set alight the screen with movement, not dance alone. Take Pyaasa’s Jaane Kya Tune Kahi, for instance, where she does not really dance, only scampers with otherworldly grace, rhythm and abhinaya, or expression. Her director and co-actor, Guru Dutt, had offered her a work contract after witnessing a commotion for her and other stars of the Telugu film Rojulu Marayi (1955), on a road in Hyderabad. Rehman had the dance number Eruvaka Sagaro Ranno Chinnannaa in the film that became so much of a rage that audiences would ask for the song to be re-played after the film was over.

Thereafter, she performed the song for the Tamil remake of this film, Kaalam Maari Pochu (1956), opposite Gemini Ganesan, played a princess opposite N.T. Rama Rao in Jayasimha (1955) and did a dance number in the Tamil film Alibabavum 40 Thirudargalum (1956), starring M.G. Ramachandran, Kabir’s book notes. In her first Hindi film, CID, where Rehman plays the vamp, notice Shamsad Begum’s Kahin Pe Nigahen Kahin Pe Nishana—the song begins with Rehman tying the ghungroo. Remember also that Guru Dutt trained as a dancer with Uday Shankar and wanted to be a dancer before Shankar’s school folded—it is understandable then that he recognised a fellow dancer and marked her out as such.

Rehman is the only leading woman to play the performing woman repeatedly in the 1950s-60s in Bombay, the decades immediately after independence, when the anxiety about respectability and reform ran high. Her seniors in the Bombay industry (later her contemporaries), Madhubala (Mumtaz Jehan Begum Dehlavi) and Meena Kumari (Mahjabeen Bano), both played courtesans in prominent films—Mughal-e-Azam (1960) and Pakeezah (1972), respectively. But these are period pieces, unlike Rehman’s list, which is all set in the present. Nargis, the grand-daughter of the courtesan Daleepbai and daughter of the pre-eminent courtesan, composer and producer in Hindi films, Jaddanbai, tended to play schoolteacher and lawyer—educated Bhadramahila figures—in her filmography. She played a performing woman only once in her career, in Adalat (1958). Nutan, possibly the only woman star to deliver hits without a major male star in these decades, did not play a performer in any notable film. Rehman’s closest comparison is Vyjayanthimala Bali, another glorious dancer and superstar whose longevity matches hers, and a fellow Tamilian. Vyjayanthimala played a courtesan in Devdas (1955) and the period film Amrapali (1966). But she is a Hindu.

The ‘Nachne-Gaanewali’

The Muslim woman has long been stereotyped as the tawaif, performing woman or the nachne-gaanewali—the disrespectable woman in the public mind—a stereotype created in part by popular Hindi cinema. The reason for this is at least partly historical.

For the first several decades of the Bombay film industry in the early 20th century, a number of Muslim women emerged as pioneers in the newly-emerged technologies of cinema and sound recording. The women who possessed the competence for cinema or recording were those trained in performance—from the tawaif, devadasi or other performing cultures, or the stage. Gauhar Jaan, the first Indian woman known to record her voice between 1902-04, was a tawaif in Calcutta (Kolkata). Her contemporary, Jankibai of Allahabad, another gramophone superstar through at least 1928, was a courtesan in Allahabad (Prayagraj). The names of Jaddanbai and Fatima Begum, who began as a stage actress, have already come up.

The female playback stars of the 1940s, the decade when playback took off properly, were almost all Muslim—Shamshad Begum, Noor Jehan, Amirbai Karnataki, Zohrabai Ambalewali. Of them, Amirbai Karnataki, one of the leading playback singers in Bombay in the 1940s, came from a family of performers in Marathi musical theatre. Amirbai’s rendition of Vaishnav Jan Toh is said to have had an admirer in M.K. Gandhi. The legendary Noor Jehan’s parents—Madad Ali and Fateh Bibi—were musicians, although it is not clear if she is of tawaif lineage.

Not all of them came from courtesan or performing lineages. The precocious talent of Ambalewali and Begum in their girlhood is documented in interviews and a handful of stories, but their families do not appear to have been associated with the performing arts. The association of the Muslim woman with the performer’s identity is, thus, understandable when you consider their enormous legacy in the industry. But why was the performing woman perceived as a woman of shame in the first place?

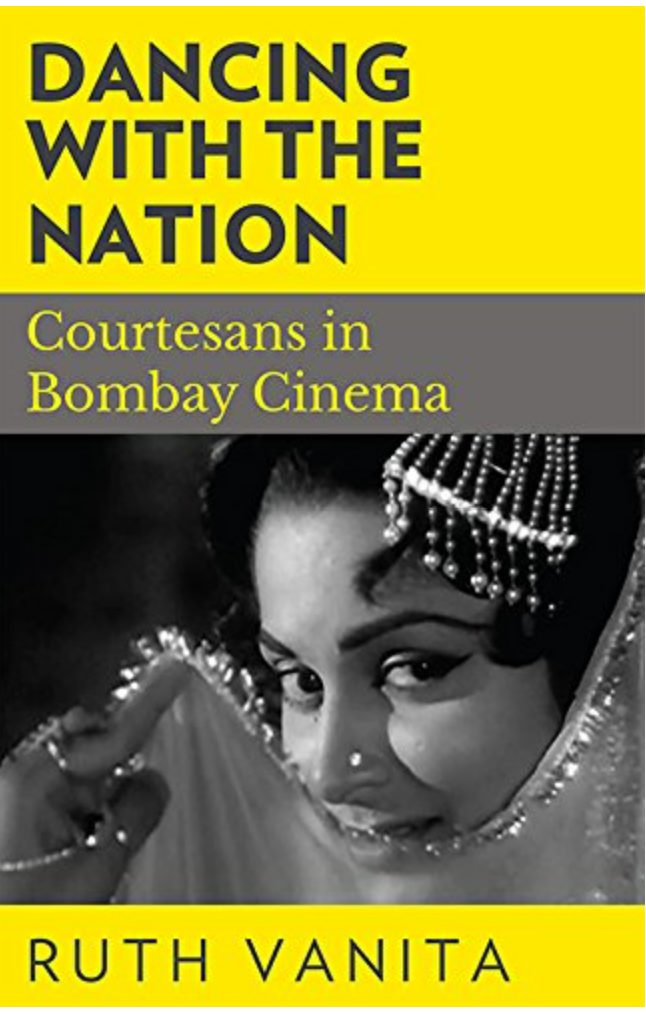

1857, and the prejudice against pleasure

The academic and writer Ruth Vanita writes, in her book Dancing With the Nation, Courtesans In Bombay Cinema, that the revolt of 1857 was followed by the British colonial government cracking down on the north Indian cities that served as nodes of the movement. Consequently, the source of the patronage of performing lineages such as tawaifs dried up.

Moreover, a tide of prudishness had swept Victorian England in the late 19th century and washed over India as well. This took the form of social censure against tawaifs, devadasis, performing cultures, contributing in part to what is known as the anti-nautch movement in the south, leading to the marginalisation of hereditary devadasis from their temple dance form. The so-called sleaziness of song and dance and performance was the rare subject on which national movement leaders were in agreement with colonial administrators and missionaries. The British conflated performing artists with prostitutes. And the Hindi film industry has continued this flattening—the figures of the tawaif, devadasi, prostitute, bar dancer, actor blend into each other.

The national movement held up the figure of the Bhadramahila—the educated woman who embodies the traditional values of a good wife and mother—against the “fallen” figures of the performing woman, the only public-facing women of pre-modern India. It is also in this context that we begin to understand why the Muslim stars of the Bombay industry had to adopt Hindu names—the men because they were seen as members of the community that broke the independence movement, and the women because they were seen as legatees of performing women. The anti-Bhadramahila. Although the Bombay film industry is shaped by the work of many tawaifs, devadasis and women from performing lineages, their identities have been obscured with Bhadra markers.

When you consider this history of Bombay cinema and its simultaneous reliance on, and discomfort with, women from performing lineages, do you see how much of an outlier Rehman is?

One explanation may be that it was easier for her to take on these roles because of her background: Her father was an officer in the Indian government service who had eschewed his zamindari, she tells Kabir in Conversations With Waheeda Rehman. But perhaps this diminishes her own say in these choices.

“As I see it, an artist should not have restrictions—that I should do this, I should not do that, what can become of this?” Rehman says in a video interview available on YouTube. “She (Gulabo in Pyaasa) was a good girl. Her circumstances made her become a streetwalker. But now that she has taken this up as a profession, she sings songs and draws people in with her allure, Guru Duttji told me.”

It was a lesson she carried well with her. Every major leading woman in Hindi film played a courtesan or performing woman at least once in their careers until the 1990s, but very few accomplished it with such a palpable sense of professional pride in the performer’s persona, demarcating this clearly from the difficult (or maudlin) circumstances that Hindi film defines their characters by. What she brought to the courtesan and streetwalker and dancer and every performer is a professional’s competence. And pride.