Ray’s cinema is known for its magnificent portrayal of the inner lives of women. But Ray the writer, whose legacy of young adult stories in Bengali is even greater than his films, has a pathological absence of women in his books. What might this chronic exclusion amount to in the minds of his fans?

Every summer, at this time of year when the heat is homicidal, a festival of nostalgia is held on the first weekend of May in Kolkata that provides the brief shade of affectionate reminiscing. 2 May is the birth anniversary of Satyajit Ray, arguably one of the three best-known Bengalis across India (the others being Rabindranath Tagore and Narendranath Dutta, better known as Swami Vivekananda), and news media is splashed with special issues and programmes devoted to Ray’s genius. In fact in the Bengali mind, his status is equal to Tagore, I would say. Vivekananda, while revered, is more of a hoary presence—a holy man whose thoughts and work are imagined to be great (which they are in fact) but precise knowledge of which are nebulous.

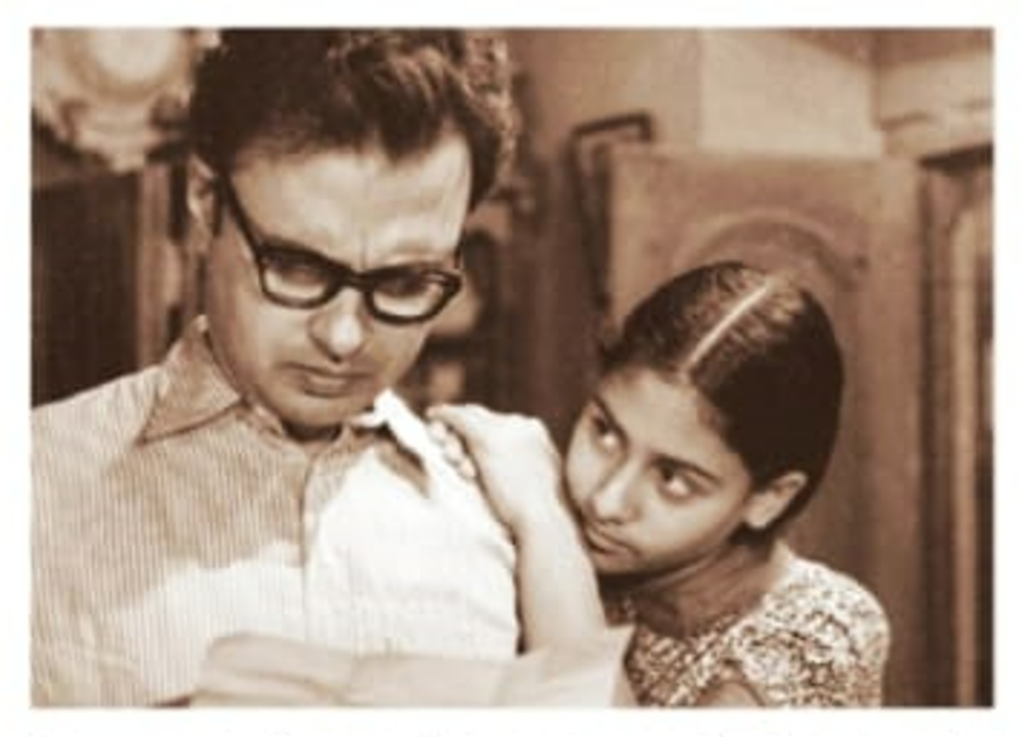

A couple of actors with pan-Indian appeal will write about shooting with “Manik da”—usually Sharmila Tagore and the recently deceased Soumitra Chatterjee. A couple more will speak of how they wanted to be cast in a Ray film and came close. Then a couple of contemporary directors will pick their favourite Ray films and articulate how they were shaped by that particular film. Someone will write about his musical compositions. A couple of contemporary writers will reflect on what they learnt from Ray, the beloved young adult writer (and truly his succinct prose, sparkling with wit, is a treasure).

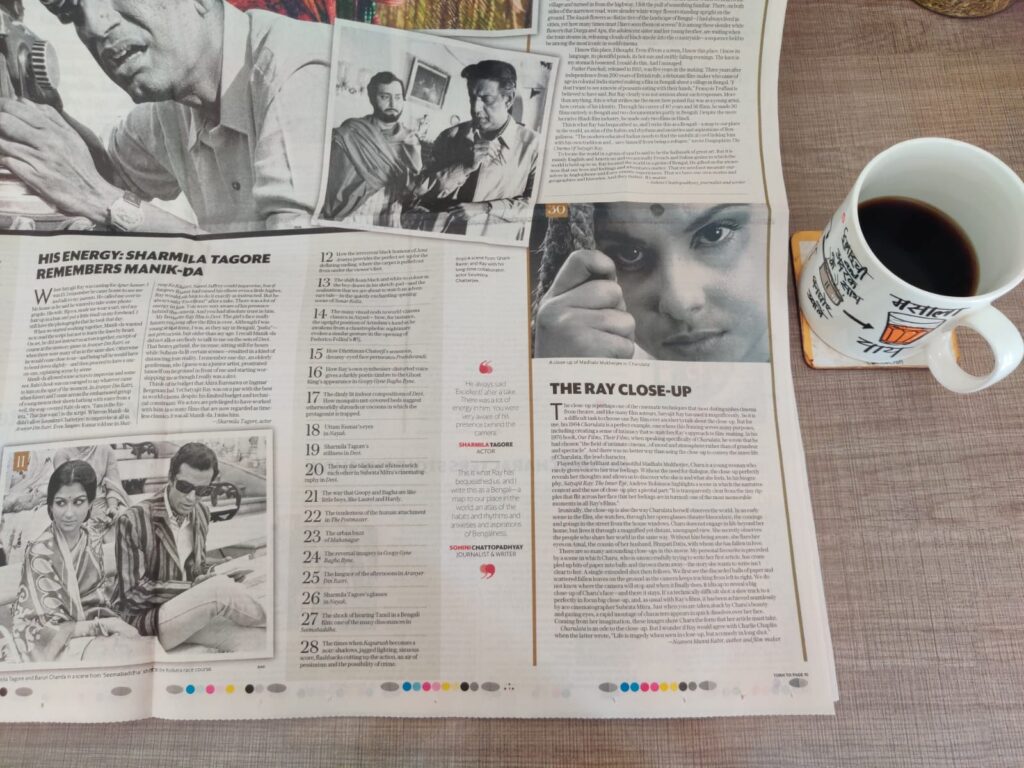

Mint Lounge‘s marvellous special issue to mark Satyajit Ray’s centenary in 2021. The piece occupying the bottom left is by Sharmila Tagore, who acted in five Ray films.

To be clear, this splash of Ray nostalgia is very enjoyable even if hagiographic. Sharmila Tagore, for instance, is a superb mind, the anomaly among actors of her generation who can speak confidently about technical details alongside personal anecdotes: How Ray handled the camera himself when he shot the memory game sequence (which holds cult status for Ray-philes) in Aranyer Din Ratri, and how heavy it was, yet how smooth and steady it looked on screen. How the sequences up till the stairs of Apu’s chilekotha (terrace room) in Apur Sansar were shot in a real location, but the room itself was a set constructed by the master designer Bansi Chandragupta. Last year at a screening of the restored Mahanagar, the actor Jaya Bachchan spoke of how cinematographer Subrata Mitra spent hours setting up the lighting for each indoor shot. How Sharmila Tagore and the iconic Bengali actor Rabi Ghosh had scouted the 15-year-old Jaya for the cameo in Mahangar, when she was on holiday in Puri with her father.

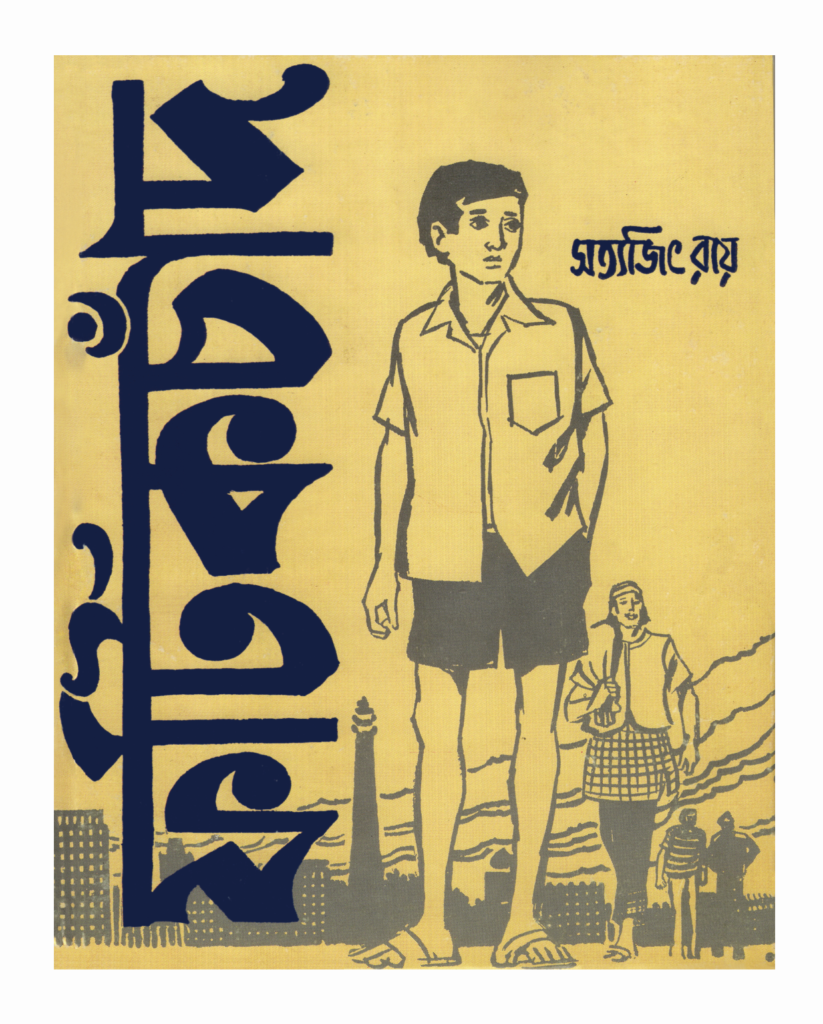

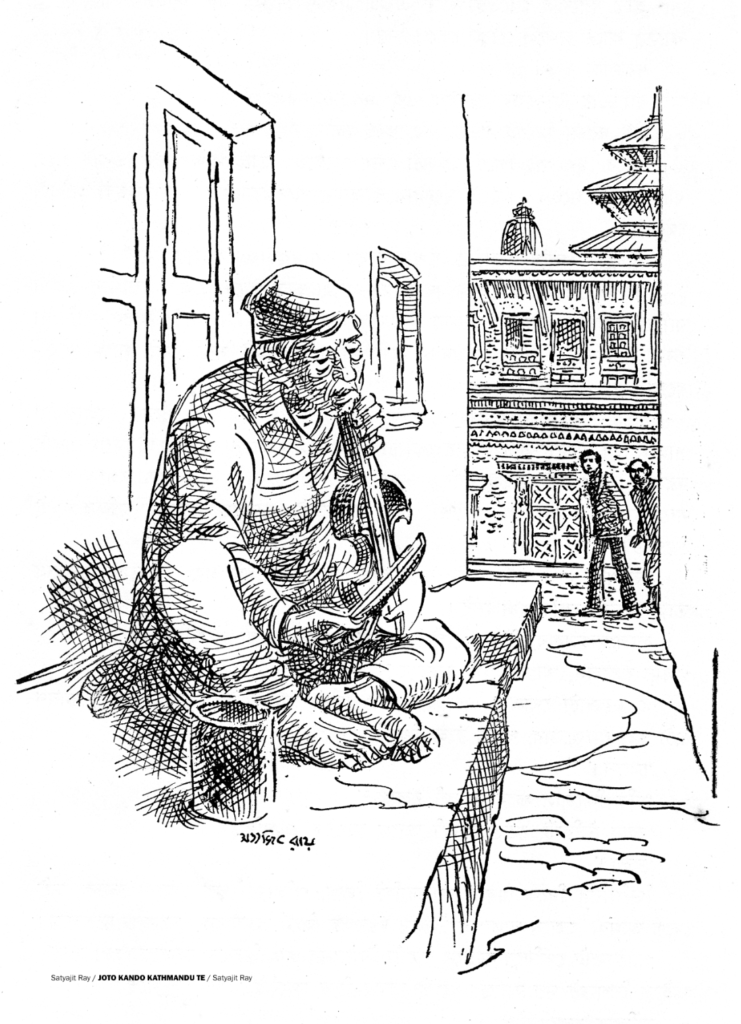

More recently, his graphic design and typography is being talked about in some detail (although his work in this department has been a high school quiz question since I was in high school). It is quite something to hear how elements of Ray’s books have influenced writers in recent generations. I notice how Suchitra Bhattacharya’s Mitin Mashi series doffs its hat to Ray’s map of Calcutta by its well-known food and beverage places. How his music continues to make us hum beloved songs. “After all, this is Manik da we are talking about!” a recent friend who has worked with Ray often exclaims. “Even his worst is excellent!”

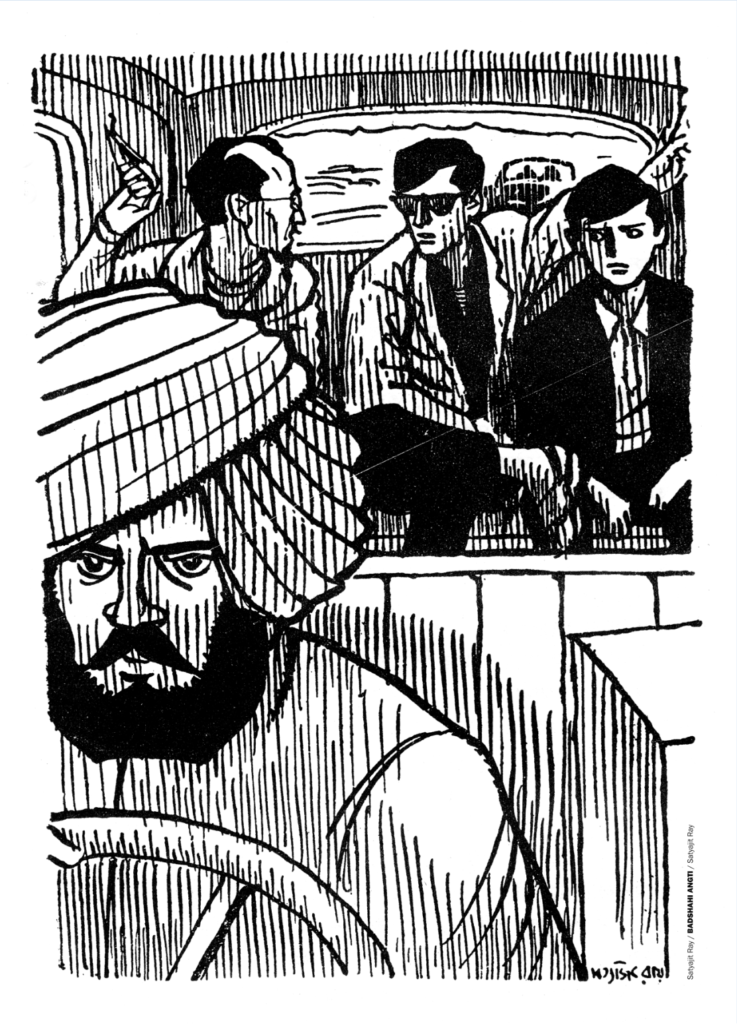

What gets no space, however, is any thoughtful essay that questions Ray, however mildly. I don’t mean criticism, but thoughtful questioning that comes from a place of admiration and/or love. This is especially true of the Kolkata media, both Bengali and English-language, but also true of the so-called pan-India publications. A couple of years ago, on the occasion of Ray’s centenary, my favourite features magazine invited me to write on a special issue devoted to Ray. It remains one of the high points of my 15-year plus career as a journalist-writer. I asked the issue editor, a writer I enjoy and a calm and thoughtful editor who has welcomed my work in general. I wanted to write on Ray’s exclusively male universe in his excellent set of books for young adults, comprising broadly the Feluda series, the Prof Shonku set, the Tarini Khuro stories, and the collections of short stories usually published in bunches of 12. There are no significant women in these books, not even as supporting characters. For a filmmaker known for his intelligent portrayal of women, this is a strange decision. That all his books for young adults—Bengali literature calls it Kishore Sahitya, which does not translate to children’s literature—have a wholly male world is odd, isn’t it? Did women play no role in the world in his own imagination?

The young, thoughtful editor did not accept this pitch. The idea was to celebrate Ray on his centenary, he told me, think of something else. So I did, but I was surprised. Ray had been gone 29 years the summer of 2021, the year he turned a hundred. His debut Pather Panchali (1955), received with raptures in 1956, was 66 years old. He had been celebrated, justly so, for 65 years and counting as an icon. On his centenary, it should have been okay to note how his imagination as a writer was wholly male, shouldn’t it? In fact, wouldn’t it befit his iconic stature to engage with his vast body of work with new-ish perspectives, opening them up to more thinking, as against reverence?

Perhaps I am being unfair to the pan-India publication. A special issue on Ray outside Bengal would be presumptuous to assume that readers were familiar with his vast output as a writer in Bengal. It would have been a better choice for a publication in Bengal—a readership that would be able to discuss the many Feluda and Shonku and Tarini Khuro books in detail.

But realistically, there is no chance of such an essay finding space in the mainstream press in Bengal—English or Bengali. Very rarely, an eye-brow popping contrarian perspective will be carried; the edgy filmmaker Q stating that Ray’s perceived brilliance was on account of his handsomeness, for instance. Clickbait stories, in other words. But asking thoughtful questions of Ray’s work is not permitted, even if these are questions that have been bubbling up in conversations for a while.

Now that I have got that grievance out of the way, here is my thought, written for a publication that would indulge me with space–my own website. How do we respond to the realisation that Ray’s writing (phenomenally popular in Bengal, and said to have made him a crorepati) has a singularly male perspective? Doesn’t it suggest that Ray thought women’s lives had nothing of interest to young minds coming into their own? (Another question: what is with Simi Garewal’s atrocious black-facing in Aranyer Din Ratri—has anyone analysed that seriously in a mainstream publication?)

The missing women is not an especially original observation. I first heard this from a professor in my (aborted) law school stint. “Why is Ray’s book-verse devoid of women?” she had asked. 18-year-old me, freshly orphaned from my school moorings and clueless in the wider waters of university, had been stunned. “If Feluda is gay, then why not explore that homosexual dynamic,” she added, with a laugh.

No one in my life had ever questioned Ray so far. My parents had been proud that I read Ray’s books as much as I read Enid Blyton in the primary school years, and Agatha Christie and the Hardy Boys in the high school years. In fact, they had asked me to read beyond Christie and Blyton, but never beyond Ray. (And there are many, many Bhadralok middle and upper middle class Bengalis like them. In fact, the entire personality of several Bengali men is Ray fandom.)

But the professor was right, I realised when I thought about it. There are no women in Ray’s books, leave aside a character like Miss Marple who navigates a distinctly elderly and feminine way in the world, upending not only patriarchal norms of storytelling, but also age.

For a man presumably in his thirties, Feluda’s life is oddly absent of any mentions of love, longing and/or sex. Perhaps he is asexual, one of the things that the A in the LGBTQIA spectrum (full list of terms here), stands for—a person who does not feel sexual attraction. This is distinct from celibacy, which is wilful abstention from sex. Is Feluda celibate? We don’t know, because there is no mention of his sexuality at all. But awareness about the diverse strands of sexuality was not what it is today when Ray was writing these stories, you might say. Fair point, but wouldn’t there be some reflection on his single status in a marriage-mad society like south Asia?

If you think about it, Ray’s multiverse feels like something out of a work of science fiction, where women have been left out. Like a sequel to Margaret Atwood’s novel A Handmaid’s Tale where there were two categories of women—the child bearers, and those who have outsourced birthing to the bearers. Or a chapter of one of those Noughties Hollywood films, where Will Smith saves the day on a planet beset with cyborgs and/or aliens. Or, one of those 1980s Hollywood Cold War films where white men mumble to one another in dimly-lit surroundings with large shadows and try to save the world from imploding. Often, these films feature at least one woman—there is usually a love interest in the plot.

The melancholic love interest is a stereotype far from ideal, but Ray’s stories do not have even this. (Unlike the Cold War films, however, there is no vaguely threatening undertone to his world—everything is cheerful and much-as-usual. And arguably, that makes the absence of women odder.) None of his heroes appear to need love in their lives. His most beloved character Feluda, the brilliant 30-something private detective who restores justice, armed with a revolver and his smarts, is not coupled. His accompanists on his adventures are his teenaged nephew Topshe, and bumbling friend and admirer Lalmohan Ganguly. These two are not there to help Feluda, but to act as a proxy for readers to explain things to. Feluda does not have a mother either, nor does he mention one. He appears to live with his uncle, but there is barely any mention of his aunt. Undoubtedly, a good quizzer will be able to point to at least half a dozen examples where the aunt makes an appearance, and I note this with affection, not scorn. But the point remains, there is no female presence in Feluda’s world that registers in the reader’s mind.

For a man presumably in his thirties, Feluda’s life is oddly absent of any mentions of love, longing and/or sex. Perhaps he is asexual, one of the things that the A in the LGBTQIA spectrum (full list of terms here), stands for—a person who does not feel sexual attraction. This is distinct from celibacy, which is wilful abstention from sex. Is Feluda celibate? We don’t know, because there is no mention of his sexuality at all. But awareness about the diverse strands of sexuality was not what it is today when Ray was writing these stories, you might say. Fair point, but wouldn’t there be some reflection on his single status in a marriage-mad society like south Asia?

And what about Topshe, the teenaged boy who serves as manual jobs assistant and narrator to Feluda? Isn’t he the age when the hormones rage and crash? How does Topshe have a similarly indifferent attitude to romance and sex? With Feluda, you could argue that he has tried his hand at love and sex, and come to realise that he doesn’t have the taste for either. Indeed, Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple appear to be similarly asexual, a sparkling essay in Salon notes. But how is it that every major character in Feluda’s world—Topshe, Lal Mohan Ganguly and mentor figure Sidhu Jaetha being the other three —appear to be asexual too?

One argument is that Ray wrote these books for children, and so, there is no sex and violence. Fair enough, although I feel there is a spectacular opportunity lost to introduce young minds intelligently, gently to sex given how well Ray writes on science. But my point is not sexuality or romance per se. It is the absence of women in Ray’s stories. Both the Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot series feature interesting women—the unforgettable Irene Adler in Holmes’ case and the enigmatic Vera Rossakov in Poirot’s case.

Ray’s cover for Khai Khai (Nom Nom), a book of nonsense verse written by his father Sukumar Roy. I find it striking that all the figures shown eating are male

Consider Professor Shonku, the elderly scientist that Ray acknowledged was partially modelled on Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger, and partially on his father Sukumar Roy’s character Hesoram Hushiyar. Shonku, who reminds me of the adorable Prof Calculus in the Tintin books, is single and uncoupled. You might point out that Tintin also appears to be single and asexual. But there is a woman in the Tintin universe—the larger than life and entirely lovable opera singer Bianca Castiafore, who seems to have an ongoing thing with Captain Haddock. Castiafore appears in several Tintin books, and is a prominent character with a defined set of quirks.

Consider also Ray’s Tarini Khuro books, based on a protagonist fond of telling make-believe stories along the lines of Narayan Gangopadhyay’s Teni da and Premendra Mitra’s Ghana da, terrific armchair adventurers. Khuro (which translates to elderly uncle in Bengali) also has no women in his world. From what I remember, those who gather to hear his stories are mainly young men.

Then, there are the short stories, and Ray is a master of the form. Particularly, paranormal stories. Here too, pretty much every ghost story I remember is peopled with men. In this he is an anomaly, because ghost stories tend to feature women far more than men, given that women have been at the receiving end of injustice through the ages. The figure of the melancholic or vengeful spirit is usually female. But not, in Ray’s world. All the tortured ghosts—colonial administrators, workaholic painters, even dolls (I am thinking of the superb story called Fritz)—are male.

Ray was also a charmingly original writer of science fiction; his story ‘Bankubabur Natun Bondhu’ (Bankubabu’s New Friend) is widely believed by Ray-philes to be the basis for Steven Spielberg’s ET. (Spielberg’s view is that ET is his own original work.) Nevertheless, here is the story: a harried school teacher encounters a friendly being from another planet on his way back home one day, and the two strike up a friendship. In another story, titled ‘Onko Sir, Golapibabu aar Tipu’ (The Math Teacher, The Pink Man and Tipu), a boy called Tipu encounters a pink being, evidently from a very different world. The writer Shrabonti Bagchi references this in an excellent piece on Ray’s children’s writing, where she briefly notes her disappointment with Ray’s singularly male perspective.

“Are you sad?” the pink man asks Tipu. “Well, I am disappointed because I was looking for a mongoose and can’t find it.”

“Not that kind of sadness—I mean the kind that makes you go blue behind your ears, that makes your palms go dry.”

How movingly he could write about childhood loneliness and sadness, subjects that even now receive little attention!

What does it do to our sense of self to read a lovingly-built world in a familiar city where those who are like us—in this case, women—simply don’t exist? In every other way, it is a known and pleasant world where injustice is righted and reason and goodness prevails. Does it make us feel, perhaps, that nothing meaningful, no adventure, no quest, no truth worth knowing happens to women? That to do something that matters, we have to be male?

So what is my complaint then? That I loved Ray so much I read him ceaselessly from the age of 9 to 13, yet the stories never had anyone like me–a young girl, a woman, or an old woman. Why couldn’t it be a Bonku di who encountered the alien? Why not a genius Sidhu jethima instead of jaetha?

I did not realise this consciously when I read the books, although once I stopped reading Ray around 13, I never went back to re-read him in the way I have returned to Christie and Wodehouse in my twenties and early thirties. Perhaps, there was something that felt unnatural in that world, like the Enid Blyton books I once devoured, seemingly possessed.

What does it do to our sense of self to read a lovingly-built world in a familiar city where those who are like us—in this case, women—simply don’t exist? In every other way, it is a known and pleasant world where injustice is righted and reason and goodness prevails. Does it make us feel, perhaps, that nothing meaningful, no adventure, no quest, no truth worth knowing happens to women? That to do something that matters, anything at all, we have to be male?

I’ve always been a tomboy, and taken pleasure in it. I don’t think I have ever felt especially feminine, but from my thirties, I have enjoyed saris, particularly the draping of it. I give the credit for this tomboyishness partly to Ray, and partly to mainstream popular culture in English and Hindi, where men do all the things that are Important, Interesting, Intrepid. I enjoy being independent, believing I should be able to afford whatever I want myself, hoisting my luggage unassisted into wherever it needs hoisting, going to the cinema alone, going to the doctor alone and taking decisions on family health crises by myself.

Yet lately, I have come to wonder about some things. Do I always need to lug my luggage myself? Buy gifts for the men I am seeing? What’s wrong with make-up and why must I be so bad at it? Perhaps there is some sense in moving leftovers from larger utensils to smaller utensils before putting them in the refrigerator like my mother does, and grandmother did? Most of all, have I diminished women who do womanly things? Have I, perhaps, not registered these women, their interiority at all?

It was a realisation that dawned when I watched the chamber dramas of the late filmmaker Rituparno Ghosh, who draws out the inner lives of housewives and quiet domestic women astonishingly well. In fact, this is something Ray did masterfully in his films too, particularly Charulata, about the loneliness of a young wife married to an older professorial man in 19th century India, and Mahanagar, about the growing sense of self of a housewife who steps out to work a job in turbulent 1960s Calcutta. Even more delightful was the supporting character of the teenaged sister-in-law of the protagonist Arati, played superbly by a debutante Jaya Bhaduri, a studious adolescent who fantasises about the lives of film stars.

How did a person who brought women’s interiority to screen as intimately as he did, write stories devoid of women? For that matter, how did a man who understood childhood and its extravagant fantasies and desolate loneliness like him, who loved Tagore as much as him, never set out to imagine what it was like to be a girl child? How did he never write a character like Jaya Bhaduri’s Bani again, the adventures of a studious film fan?

Am I blaming Ray for my cognitive blindness? I hope not. We are not only the books we read, the films we watch or the people we see around us. We are all of these, and more; most of all, we are the people we choose to be. Within this framework, I am trying to assess the influence his writing has left on me. I am, also, trying to assess how a writer I once loved to the exclusion of others became a writer I never returned to re-read.

I think I was always an outsider in his vividly-drawn world of decency and rational humanism. I never belonged in the way that I could see myself in action alongside Feluda or Shonku or Tipu and Golapi Babu. I was the outsider, peering in. And once I stepped away, I did not come back.

It’s not the kind of sadness that leaves me blue behind my ears. Or dries my palms. Only a disappointment that Ray, the writer I loved (and still love), did not see me as one of his own.

My book The Day I Became a Runner offers an alternative history of the republic, from the late 1930s to the present moment, through the lives of 9 women athletes. It is available on Amazon and bookstores across India.

8 comments for “Satyajit Ray and the Case of the Missing Women”