In Hindi film, the woman is rarely the protagonist of a Partition or Independence narratives. But Bengali film always centers the experience of women in such narratives. An introspection

The 2018 Bengali film Ek Je Chhilo Raja, while largely mediocre, has an interesting question towards its tail. The film centres on a real-life legal battle for property in India, known as the Bhawal Sanyasi case. One day in 1921, an ascetic with matted hair and ash smeared all over his skin was found in the vicinity of a large Bengali zamindari estate. He resembled the second son of the estate, a prince with a talent for wasting money in the manner of the Bengali babu of the day and an insatiable libido despite having a young wife.

The prince had left for Darjeeling to recover from syphilis nine years earlier, and was said to have died there. The judicial proceedings, which took place over 13 years and in courts across present-day Bangladesh, India and the UK, ruled that the ascetic was, in fact, the second prince of the estate. The film is mostly faithful to A Princely Impostor (2002), a novel-like book by the scholar Partha Chatterjee.

The case, which coincided with the most rousing decades of the Independence movement, also came to acquire nationalistic colours. In the return of the once-dead prince, his subjects saw a man of the land come back to protect his people from the British. Why else this portentous return?

The one moment in the otherwise turgid film that carries real emotional charge comes when director Srijit Mukherji turns away from his dutiful adaptation to ask a feminist question. Are we right to consider the spoilt prince a hero because he is now a silent and remorseful ascetic, bereft of desire save a fondness for mishti doi? Or should we re-evaluate his story in the light of his callousness toward women? These questions are raised by a well-known lawyer, a character played by actor-director Aparna Sen. Freedom is good but does it change anything for women, she asks.

Sen’s subplot, however maudlin, adds a nice touch of complexity to the Independence narrative. Quite a few prominent Hindi films have been made on the Independence struggle and the Partition. The most recent of these is Bharat, Salman Khan’s swaggering romp through 70 years of Indian history, telling the story of a Partition refugee who builds his life with that of the new nation. Towards the end of the film, you realise this is a tale of a brother and sister who got separated during the riots of 1947, but the story you see on screen is only that of the brother, who heroically shapes his life around the childhood loss that defines him. The first half of 2019 has also seen a film called Kalank, another story about the Partition, and Manikarnika, on the life of the 19th-century queen Lakshmibai, who fought the British.

In 2018, there was Gold, a fictionalised Bollywood production about India’s first hockey gold at the 1948 Olympics, and Thugs of Hindostan, about a fictional band of pirates who take on the British. There was also Manto, Nandita Das’s film about the writer’s dislocation post-Partition. The big-budget turkey Rangoon, about Subhas Bose-supporting rebels in the Independence movement, was released in 2017.

Over the years, actor-director Aamir Khan has shown a fondness for taking the British on — he did so in Lagaan, Mangal Pandey: The Rising, and Rang de Basanti. Among other such films were Gadar: Ek Prem Katha, 1942 A Love Story and Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, aside from biopics on figures such as Bhagat Singh, Sardar Patel and Ambedkar.

Plots, subject, and tonality vary, but in all these films, one thing is common: The women are never the central subjects of Independence or the Partition. What they experience, what they articulate (if they do) are echoes of what the men do. Sometimes, the women are just props: Remember how Gracy Singh’s character was dropped from the cricket team in Lagaan the moment they had 11 players?

Manikarnika is different, of course. Not only does Kangana Ranaut’s queen feel the slings and arrows of outrageous colonialism keenest, much more than her gentle husband, she also trains the women of her kingdom to take up arms against a sea of British imperial might. But this is just one film. Nargis Dutt’s Mother India is different, too, for it does not look at overtly political events but on the story of the imagined Indian village.

More than anything else, Ek Je Chhilo Raja underlines just how different Bengali cinema is in this respect, how women have a distinct take on colonialism, nationalism and the Partition, whether she is a larger-than-life queen or a housewife learning to write or a lawyer unusual for her times. Their experiences are distinct from those of men, because men and women lived vastly different realities in the colonised subcontinent, leading to perspectives which are much more nuanced — they are less celebratory about Independence and less brooding about the Partition.

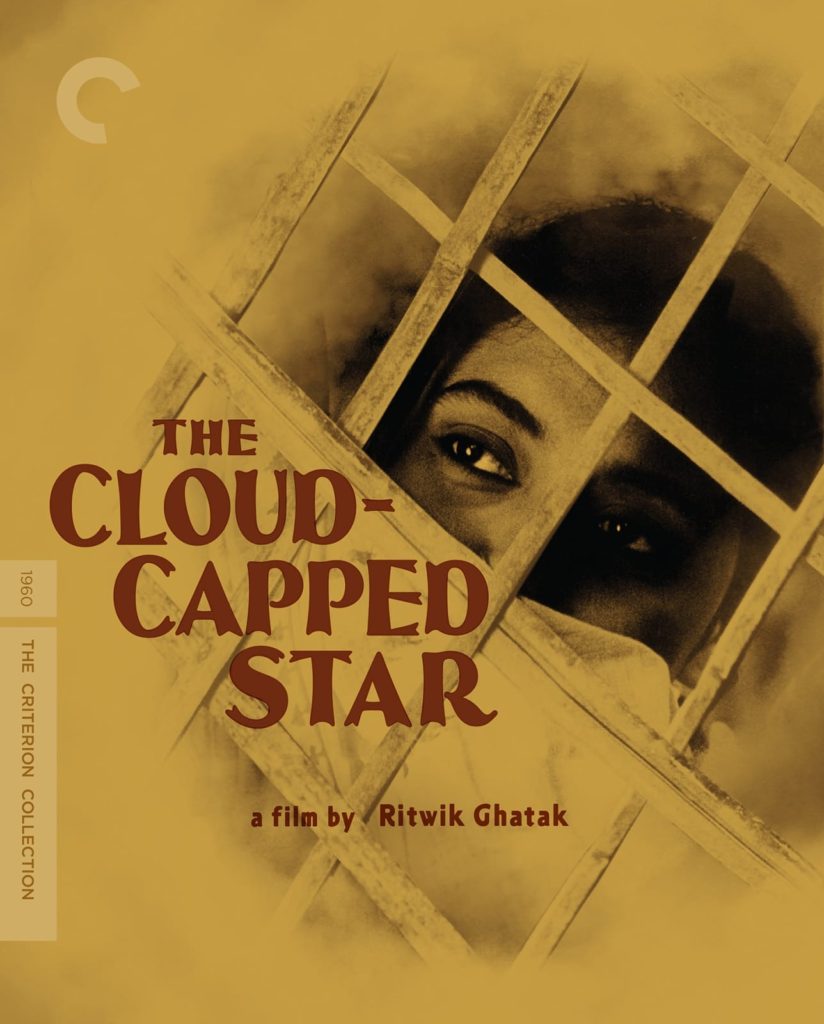

The female experience of the Partition, for instance, is of backbreaking work and forbearance rather than trauma. We see this in Ritwik Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), where a daughter works herself to death feeding her refugee family, but not in Manto, which foregrounds the writer’s alienation and sidelines his wife’s lovely, warming presence.

Perhaps this was because all the social reform in 19th-century colonial India concerned women — sati, widow remarriage and women’s education being the most well-known. The lives of middle-class women in Bengal had changed more rapidly during this time than it had in the centuries earlier, Chatterjee writes in his essay Colonialism, Nationalism and the Colonised Woman, published in the journal, American Ethnologist.

Independence and the Partition are more than the patriarchal triumphant story of India told by Hindi cinema, textbook history and a muscular government. In Srijit Mukherji’s Rajkahini (2015), the Radcliffe Line dividing India and Pakistan on the eastern side is set to pass through a brothel, run by Begum Jaan. The women at the brothel refuse to leave when presented with an eviction notice from the governments of the two new countries. “Whether it is the British who rule or Indians, it is always men,” says Begum Jaan at one point in the film. The women die defending their little patch of freedom. The Bengali film was remade in Hindi as Begum Jaan — and is possibly the only Bollywood film where Independence and the Partition are viewed through the eyes of women.

Several decades previously, there was the pulpy Bengali hit Debi Choudhurani, based on the novel by Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay. A high-caste family throws out its young daughter-in-law because of rumours about her character. Under the training of a gang of pirates, she becomes Debi Choudhurani, a Robin Hood to the poor and a symbol of the resistance against the British. The British, however, are only a titular enemy; the real nemesis is the Brahmin father-in-law.

The Tagore stories Charulata, Ghare Baire and Chokher Bali all position their heroines stepping out of the threshold of domesticity into the world. Rituparno Ghosh’s 2003 cinematic rendition of Chokher Bali, set in the time of the first Partition of Bengal in 1905, deals with the young educated widow reduced to a life of dreary domestic chores because of her widowhood. Hungry for life, she has an affair with her best friend’s husband, ushering in chaos.

“When I left Darzipara Street and came to Kashi ghat, I think I realised what desh means. I realised there was a world outside our kitchen, and rules of the kitchen and household. We had only read about this in books and stories, but it’s really out there. Whatever passed between us, promise me that the child growing in your womb, girl or boy, will not be confined to that house on Darzipara Street,” writes the widow in what is arguably the most beautiful closing sequences in cinema.

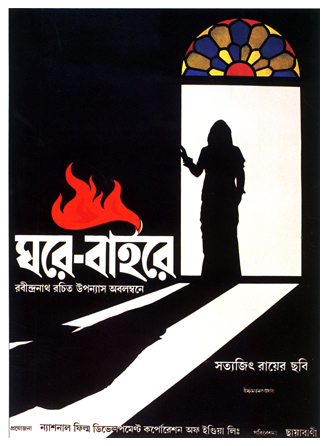

In Satyajit Ray’s Charulata (1964), set in the years of the National movement, a housewife channels her boredom into writing; education is the representation of her encounter with colonial modernity. In his Ghare Baire (1984), a zamindar introduces his wife to his nationalist friend because he wants her to read, meet people and step out into the world. She falls in love with the friend, and the husband waits for her to make up her mind.

Both Meghe Dhaka Tara and Manto are post-Partition narratives of alienation and impoverishment where a woman holds the family together. But in Manto, you never hear the woman speak of herself in the way that Neeta does in Meghe Dhaka Tara. “Dada, I want to live,” she says at the film’s end when she is dying of tuberculosis. The crucial word in that sentence is ‘I’.

Goynaar Baksho is also set against the Partition of Bengal, and the genteel poverty that comes to landed families uprooted overnight. But its tone is very different, light and salty. The ghost of Pishima (paternal aunt), a widow who loved her jewellery box so much that she visits it after her death, helps a daughter-in-law establish a business, take charge of the family’s fortunes and have an affair. The philandering men, on the other hand, are mostly useless. “They’re all bastards. They had fun all their lives, and fobbed me off with a box of jewellery,” the ghost says. The plainspeak is delightful, and it never papers over the wretched condition of women in Bengal. And the sadness of having to leave a homeland behind and start again.

Why is the Bengali lens different?

It may have to do with the fact that much of 19th-century social reform was led by Bengalis, and middle-class Bengali society was shaped by colonial modernity. The work and ideas of Raja Rammohun Roy (sati abolition) and Ishwar Chandra Bidyasagar (women’s education, widow remarriage) were explored in the writing of canonical Bengali writers. Even today, Bengali film draws on these works and ideas.

What does this mean, this attentiveness to women’s experiences and admission that colonial Bengali society was viciously misogynist? In real terms, not much. West Bengal recorded the highest number of cases of domestic violence against women, according to the National Crime Records Bureau report for 2016, the highest number of acid attacks and acid attack attempts, and the second highest number of crimes against women overall. But in terms of representation, it suggests an ability to listen and accept other views. Bengali film fares poorly at representing Dalit and Adivasi voices, but its sensitivity to gender (including LGBTQ voices) counts for something.

Manikarnika has its moments: There’s that sequence where she refuses to get her hair shaved to mark widowhood. But it’s not the same thing. Smashing as she is, she is a queen, after all, a Brahmin’s daughter brought up by a ruling Peshwa, and married to a king. Her life is a world apart from the hard-up widow Binodini, neglected housewife Charulata, and the exhausted refugee Neeta. Manikarnika is too much superwoman to be a woman.

Originally published in The Hindu BusinessLine, 5 July 2019

9 comments for “Are Independence and Partition Male Experiences?”